A Tutorial for Making Online Learning Accessible to Students with Disabilities

By Sheryl Burgstahler

With their rush to move instruction online in response to the world-wide pandemic of 2020, some instructors and course designers have inadvertently left some students out of many learning activities because they have not employed well-established inclusive practices. These students include those who have disabilities that impact their abilities to see, hear, move, learn, and engage. The instructional materials below provide a path forward in improving existing offerings and designing new ones that ensure that all students can benefit from online educational opportunities. It is organized as follows.

Overview

Legal Issues

Assistive Technologies and Other Accommodations

Inclusive Design Approaches to Access

The Universal Design Framework and Principles

Tips for Designing an Inclusive Course

Web Pages, Documents, and Videos

Instructional Methods

Accommodations

Final Thoughts

Resources and Acknowledgments

Overview

In this module, I provide self-paced instruction to help you get started in making your online course accessible to, usable by, and inclusive of all students, including those with disabilities. I share tips for the inclusive design of online learning that have evolved from my efforts to teach courses that are accessible to all of my students, as well as from the experiences of colleagues who have done the same. This tutorial covers these topics and more:

- Legal issues

- Accommodations and universal design

- Principles that underpin the universal design (UD) of online learning

- Practices that are accessible, usable, and inclusive

I also include links to resources for further learning that include technical details and issues relevant to making your online course inclusive of all of your students who may be enrolled now or in the future.

So what do I mean by an “inclusive” online course? I mean a course designed so that anyone who meets requirements, with or without accommodations, will

- feel welcome,

- be encouraged to participate, and

- be able to fully engaged in accessible and inclusive activities

Simple, right? Absolutely. However, it is easier to set a goal of inclusiveness than to really make it happen. And, for me, creating a completely inclusive course without the need for some accommodation has always been a goal that I have never quite reached. Luckily, inclusive design can be implemented incrementally if you adopt a habit of continuous course improvement.

Legal Issues

One motivator for accessible design of online learning is that educational institutions have been presented with legal challenges from the US Department of Education Office of Civil Rights, the Department of Justice, and the court system with respect to the inaccessible design of IT they use, including IT used to deliver online learning. Schools presented with formal civil rights complaints represent a diverse group of  institutions, as represented by this small sample: University of Cincinnati, Youngstown State University, University of Colorado-Boulder, University of Montana-Missoula, UC Berkeley, South Carolina Technical College System , Louisiana Tech University, MIT, Maricopa Community College District, Florida State University, CSU Fullerton, California Community Colleges, Ohio State University: University of Kentucky, and Harvard University.

institutions, as represented by this small sample: University of Cincinnati, Youngstown State University, University of Colorado-Boulder, University of Montana-Missoula, UC Berkeley, South Carolina Technical College System , Louisiana Tech University, MIT, Maricopa Community College District, Florida State University, CSU Fullerton, California Community Colleges, Ohio State University: University of Kentucky, and Harvard University.

This is a club to which I hope we, at the University of Washington, will never belong.

The resolutions with the US federal government to the civil rights complaints about inaccessible IT that campuses have received point to Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 and its 2008 Amendments as their legal basis. If you would like to receive guidance regarding issues that postsecondary institutions should address in order to minimize the likelihood of a civil rights complaint about accessible IT, consult EDUCAUSE's IT Accessibility Risk Statements and Evidence.

In the context of resolutions to civil rights complaints in the US, “accessible” IT means "a person with a disability is afforded the opportunity to acquire the same information, engage in the same interactions, and enjoy the same services as a person without a disability in an equally effective and equally integrated manner, with substantially equivalent ease of use. The person with a disability must be able to obtain the information as fully, equally, and independently as a person without a disability."

Assistive Technologies and Other Accommodations

Traditional efforts to assist students with disabilities on campuses nationwide embrace a “medical model” of disability, where focus is on the “deficit” of the individual and how the person can be rehabilitated or how accommodations can be made so that they can fit into an established environment. An accommodation adjusts a product or environment to provide access to a specific person with a disability. These are examples of accommodations:

- Extra time on tests

- Materials in alternate format

- Alternative assignments

- Sign language interpreters and captioners

- Note takers

- Assistive technologies

I always anticipate that students interacting in my online course will have diverse characteristics. My course may include students who fall into the following demographics:

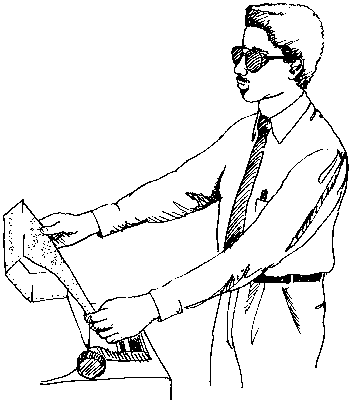

- are blind and use audible (e.g., screen readers that read digital content using synthesized speech) and/or tactile output (e.g., a refreshable braille device)

- have learning disabilities such as dyslexia and use text to speech (TTS) technologies that read aloud digital text while visually highlighting each word

- have low vision and enlarge default fonts or use screen magnification software that allows them to zoom into the screen

- have fine motor impairments and use assistive technologies such as speech recognition, head pointers, mouth sticks, or eye-gaze tracking systems

- are in a noisy or noise-free environment or who are deaf or hard of hearing and therefore depend on captions or transcripts to access audio content

- use mobile smartphones, tablets, or other devices, which have a variety of screen sizes, as well as gestures or other user interfaces for interacting with their devices and accessing content

While there are many assistive technologies (ATs) and other accommodations that allow students with disabilities to access IT and teaching practices used in your course, the good news is you do not need to have a depth of knowledge about AT in order to design accessible content pages, document, and videos for your course. Instead, you can be guided by AT limitations to determine how to design mainstream technologies so that individuals with disabilities using AT can access them. Some basic limitations are summarized in the following table.

| Assistive Technology: | Therefore: |

|---|---|

| May emulate the keyboard, but not the mouse | Design web, software to operate with keyboard alone |

| Cannot read content presented in images | Provide alternative text |

| Cab tab from link to link | Make links descriptive |

| Can skip from heading to heading | Structure with hierarchical headings |

| Cannot accurately transcribe audio | Caption video, transcribe audio |

[OPTIONAL] If you would like to learn more about ATs students with disabilities in your course might be using, I suggest you start by viewing these videos:

- Using a Screen Reader

- Our Technology for Equal Access

- Our Technology for Equal Access: Sensory Impairments

- Our Technology for Equal Access: Learning Disabilities

- Our Technology for Equal Access: Mobility Impairments

- Communication Access Realtime Translation: CART Services for Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Peopl

Inclusive Design Approaches to Access

Accommodations will likely always be necessary in specific circumstances—e.g., extra time on tests, sign language interpreters, live captioning for synchronous events. However, I recommend that more attention be paid to the design of the product or environment itself. To make this point, consider the following "Coffeepot for Masochists" from the Catalog of Unfindable Objects by Jacques Carelman in Donald Norman's The Psychology of Everyday Things, 1988.

Not many people could efficiently and safely poor coffee from this pot, which has the spout and the handle on the same side. I doubt that many of us would think that trying to simply modify this product so that it is more usable would be a worthwhile use of time. Instead, I think most of us would agree that the product itself should be re-designed so that it can be used by everyone who needs to use it.

Similarly, when it comes to students with disabilities in online learning settings, simply providing accommodations when individuals with disabilities experience access challenges may lead to inefficiencies. The “social model” of disability and other integrated approaches within the field of disability studies consider variations in abilities—like those with respect to gender, race, and ethnicity—a natural part of the human experience. This view suggests that more attention should be devoted to designing products and environments—including courses, technology, and student services—that are welcoming and accessible to everyone who might register in a course.

A goal in my courses is to make them accessible to students with a broadest range of characteristics. This may not technically include everyone, but that is what I am shooting for. "Everyone" includes students with disabilities, but also students with various learning preferences, students whose first language is not in the language in which the instruction is delivered (English language learners in the case of this course), students using a variety of devices and web browsers, and those with slow Internet connections. I know I will not fully achieve this goal, but as new versions of this course are created, I will get closer and closer to the mark, in part by listening to input from my students.

Applying proactive design practices can reduce the need for accommodations for specific students after an online learning product or activity is created. There are many practices that employ proactive design: accessible design, inclusive design, usable design, user-centered design, ability-based design, design for user empowerment, design for all, barrier free design, and universal design (UD). Although all offer contributions to the field, UD was selected as the proactive design framework on which to elaborate in this course because it has led to the most comprehensive and established principles and practices that can guide the design of inclusive cyberlearning technology and pedagogy.

The Universal Design Framework

The basic framework is underpinned by the seven principles of UD, the three principles of Universal Design for Learning (UDL), and the four principles of the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG), all described in the paragraphs that follow.

UD requires that a broad spectrum of abilities and other characteristics of potential users be considered when developing products and environments, rather than simply designing for the average user and relying on accommodations alone when a product or environment is not reasonably accessible to an individual. UD is defined by the Center for Universal Design (n.d.) as “the design of products and environments to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design.”

Basic principles of UD

Principles for the UD of any product or environment include the following:

- Equitable use: The design is useful and marketable to people with diverse abilities.

- Flexibility in use: The design accommodates a wide range of individual preferences and abilities.

- Simple and intuitive use: Use of the design is easy to understand, regardless of the user’s experience, knowledge, language skills, or current concentration level.

- Perceptible information: The design communicates necessary information effectively to the user, regardless of ambient conditions or the user’s sensory abilities.

- Tolerance for error: The design minimizes hazards and the adverse consequences of accidental or unintended actions.

- Low physical effort: The design can be used efficiently, comfortably, and with a minimum of fatigue.

- Size and space for approach and use: Appropriate size and space is provided for approach, reach, manipulation, and use regardless of the user’s body size, posture, or mobility.

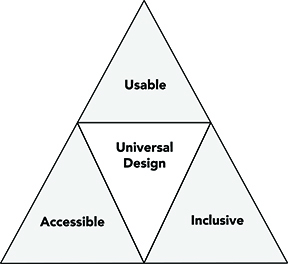

These principles, originally applied to the design of architecture and commercial products, have also been broadly applied to the design of IT hardware and software, later to instruction, and even later to student services (Burgstahler, 2015). A universally-designed space or product, including an online learning environment, is accessible to, usable by, and inclusive of everyone, including people with disabilities.

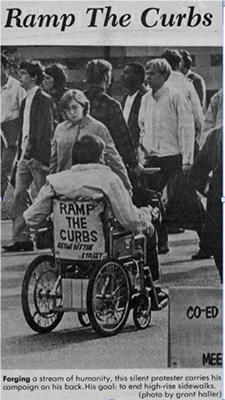

The application of UD is not new with respect to the physical environment. Back in the 1970s advocates pushed for curb cuts in sidewalks to make them accessible to wheelchair users.

“Design for all” is also used to describe a proactive approach like universal design. "Accessible design" is often used more narrowly, to ensure that products and environments can be used by individuals with disabilities. "Usable design" attends to making sure that people can effectively use a product for the purpose it was intended. "Inclusive design" is often used to describe the characteristic of a product or activity that is flexible enough to allow individuals to engage with it together.

Principles of UDL

UD practices for teaching and learning are based upon a common finding in educational research: that learners are highly variable with respect to their abilities and responses to instruction. I think this quotation from Thich Nhat Hanh, a Vietnamese Buddhist Monk, is relevant whenever the proactive UD approach is applied to the design of teaching and learning activities: “When you plant lettuce, if it does not grow well, you don't blame the lettuce. You look for reasons it is not doing well. It may need fertilizer, or more water, or less sun...”

The most common principles for the specific application of UD to teaching and learning activities are those developed by the Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST). Universal Design for Learning (UDL) recommends that curriculum and instruction offer students multiple means of engagement, representation, and action and expression, described as follows.

- Engagement: For purposeful, motivated learners, stimulate interest and motivation for learning.

- Representation: For resourceful, knowledgeable learners, present information and content in different ways.

- Action and expression: For strategic, goal-directed learners, differentiate the ways that students can express what they know (Center for Applied Special Technology, 2018).

Principles for the UD of IT

Many specific barriers to digital tools and content faced by individuals with disabilities today have well-documented solutions. These include those articulated by the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG), originally published in 1999 by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) and most recently updated to WCAG 2.1 (2018). The Guidelines dictate that all information and user interface components must follow the following four guiding principles:

- Perceivable: Users must be able to perceive the content, regardless of the device or configuration they’re using.

- Operable: Users must be able to operate the controls, buttons, sliders, menus, etc., regardless of the device they’re using.

- Understandable: Users must be able to understand the content and interface; and

- Robust: Content must be coded in compliance with relevant coding standards in order to ensure its accurately and meaningfully interpreted by devices, browsers, and assistive technologies.

While the WCAG standards were developed to apply to web-based technologies, their principles, guidelines, and success criteria can also be applied to digital media, software, and other technologies. In thinking about the design of your course, it is good to know that commonly used learning management systems (LMSs) have incorporated accessibility featured; explore the help resources or main website of your LMS to learn more. Therefore, the accessibility, usability, and inclusiveness of a course is mainly under the control of course instructors and designers.

Three sets of principles in a nutshell

Applying the combination of UD, UDL, and WCAG principles is particularly suitable for addressing both technological and pedagogical aspects of online learning in order to ensure that students are offered multiple, accessible ways to gain knowledge, demonstrate understanding, and interact. However, rather than attempting to memorize principles that underpin the inclusive design of online learning, I simply remind myself to follow these concepts:

- Provide multiple ways for participants to learn and to demonstrate what they have learned.

- Provide multiple ways to engage.

- Ensure all technologies, facilities, services, resources, and strategies are accessible to individuals with a wide variety of disabilities.

Although the need is minimized with this approach, reasonable accommodations will in some cases still be necessary to ensure full access and engagement to a particular student when the universally designed offering does not already do so. For example, a student with a learning disability engaging in a universally-designed online course may require extra time on an examination as determined by disability support personnel. Similarly, a student who is deaf may require a realtime captioner when engaging with the class using a video communication system.

UD often sounds like a good idea that no one will implement. Many people thought about curb cuts in that way. To the right is an image of an article that appeared in the UW Daily publication in 1970. the picture shows a UW students with a sign on the back of his wheelchair that reads "Ramp the curbs. Keep me off the street." He was one of the advocates for curb cuts on sidewalks so that people in wheelchairs can go from the sidewalk to the street level without negotiating a curb. There were many people who thought this was good idea but it would never happen: There were just too many curbs that would need to be redone.

Today, it is commonly accepted that sidewalks should have curb cuts. And, who benefits from them? Parents pushing baby strollers, delivery personnel with rolling carts, skate boarders, etc. As can be seen, it is not just citizens with disabilities. This is an example of the widespread application of universal design to the physical environment. It's success can encourage us to push for more educational products and environments to be accessible as well.

In summary,

- UD is an attitude, a framework, a goal, and a process;

- supports practices that are simultaneously accessible, usable, and inclusive;

- values diversity, equity, and inclusion;

- promotes best practices and does not lower standards;

- is proactive and can be implemented incrementally; and

- benefits everyone and minimizes the need for accommodations.

Start with your syllabus

Begin your journey in teaching an inclusive course by reflecting on the content of your syllabus. In my syllabus for an online course I like to, just before the standard statement about how to request accommodations, make my commitment to delivering an accessible course clear. I recommend saying something like this:

This course is designed to be a model of the application of universal design (UD)—I strive to make it welcoming to, accessible to, and usable by all potential students, including those with disabilities. The textbook is available in an accessible format from the publisher. All videos are captioned and most are audio described. The vast majority of online readings are available in accessible formats. Course materials and activities present a model of the application of UD. If you find any aspect of the course inaccessible to you or if you would like to discuss other learning issues, please contact me.

Think of other ways the wording and format of your syllabus expresses your interest in making your course inclusive of everyone who might take it.

Tips for Designing an Accessible Online Course

As I choose content, document formats, and teaching methods for a course, I remind myself that potential students have a wide variety of characteristics that may relate to gender, race, ethnicity, culture, marital status, age, communication skills, learning abilities, interests, physical abilities, social skills, sensory abilities, values, learning preferences, socioeconomic status, religious beliefs, etc. As far as accessibility, In the development of my course, I find it useful to expect that I will have in my class

- a student who is blind,

- a student who is deaf,

- a student with a learning disability, and

- a student who cannot operate a mouse.

For a historical perspective of accessible online courses by considering the first online course I taught (in 1995!) and taking a quick look at tips for making your course accessible to students with disabilities, watch 20 Tips for Teaching an Accessible Online Course.

The next two sections of this training module cover inclusive strategies presented in newest version of the short publication 20 Tips for Teaching an Accessible Online Course, along with URLs of resources with further explanations, that provide a good place to start when designing an accessible course.

Web Pages, Documents, and Videos

Nine tips are for web pages, documents, and videos.

1. Use clear, consistent layouts and organization schemes for presenting content.

Why. Clear, consistent layouts and organization schemes and presenting content in small chunks benefit all of your students, but particularly those with some types of learning disabilities, attention deficits, and visual impairments.

How. Features of the LMS you are using can be used to create the basic organization and navigation and presenting the content within your course. Specific issues that can be addressed suggestions for course instructors and designers include those that follow.

- Ideally in both a video and in text, tell students how to navigate through the course, pointing out the consistency in your organization schemes and layouts.

- Use simple page structure that is consistent from page to page and otherwise make navigating, finding content and assignments, and following the schedule intuitive.

- Keep lessons presented on content pages fairly short and consistent in length. If a particular lesson is long, consider presenting it in multiple parts.

- Break up content with subheadings and bulleted lists.

For additional guidelines for applying this tip access Accessible Documents.

2. Structure headings and lists—using style features built into the LMS, Microsoft Word and PowerPoint (PPt), PDF, etc.—and use built-in designs/layouts (e.g., for PPt slides).

Why. When headings, lists, and tables are properly structured, assistive technologies use this information to provide context to users. Following this tip is particularly helpful for students who are using screen readers to read screen content aloud. And, consistent with UD principles, a well-thought-out heading structure will make your content more understandable to all users.

How. Simply selecting text and making it larger, bold, or italic may make it look like a heading, but it will not be recognized as such by a screen reader. Using a hierarchical heading structure within a document or web page allows people who are blind and using screen readers to understand how the content is organized. When headings are formatted, a screen reader can read aloud the heading level and text, allowing the user to skim through the headings to quickly locate content of interest. Headings and subheadings can be easily structured using the built-in heading features of LMS content pages, Microsoft products, and PDFs. Headings and subheadings should be descriptive and in a logical, consistent order in order, for them to form an outline of the page content. Headings should be nested sequentially. When content items on a web page or in a document are organized with bullets or numbers entered one at a time, they do not form a collection recognized as a list by a screen reader. To make this content accessible, format a bulleted or numbered list using list format controls within the application being used. When lists are explicitly created in this way, screen readers can inform their users that they have encountered a list along with how many items are on it. To maximize accessibility of tables used to present content, use the simplest table configuration possible and include headings for columns and rows. For additional guidelines access Accessible Documents.

3. Use descriptive wording for hyperlink text (e.g., “DO-IT Knowledge Base” rather than “click here”) and make sure links are clearly identifiable as links to the student.

Why. Follow this tip so that screen reader users will hear information about the content of a page to which a link connects and will not need to read the entire page or document to hear the surrounding text that describes the destination of the link.

Screen readers can skip from link title to link title and read them to the user. Therefore, it is critical that a link title conveys clear information about the destination for the link. If you use "click here" for all link text on your website, within your content pages in your LMS, and in your documents, students who are blind and using screen readers will skip through the links on a page and hear "click here," "click here," "click here," "click here." Therefore, use hyperlink text descriptive of the destination, making it understandable without reading surrounding text. For example, if a link leads to the DO-IT website, title it “DO-IT website.”

4. Avoid creating PDF documents. Post instructor-created course content within LMS content pages (i.e., in HTML) and, if a PDF is desired, link to it only as a secondary source of information.

Why. If you design digital content to be accessible to people who are blind and use screen readers and those who have reading-related disabilities and use text-to-speech systems, the content will be more accessible to other people as well. For example, documents accessible to individuals using text-to-speech software because of a learning disability are also more accessible to English language learners who also prefer that text be read aloud.

How. The most accessible course content is that presented in a text-based and structured format within the content pages within your LMS. LMS features make it easy to format these pages using HTML. The default format for Microsoft documents is text, which makes the content accessible to a screen reader or text-to-speech software. PDF documents can be formatted in text but are often presented as scanned images. How can you tell one from the other? Try to perform a cut-and-paste sequence. If you are unable to select text to cut, the document only looks like text; it is actually an image of text. If a PDF presented online by other organizations that you wish to link to is not accessible, search the web to see if there is an accessible version available. Avoid using an inaccessible resource, but if it is critical for the course, be aware that an accommodation may need to be provided if a student who is blind or has a reading-related disability enrolls in your course. Products for creating documents and delivering online learning often provide built-in accessibility checkers and guidelines as well as document templates in accessible formats. For additional guidelines and how-to instructions, consult Creating Accessible Documents and Developing Accessible Websites.

5. Provide concise text descriptions of content presented within images.

Why. Course designers or instructors must provide alternate text descriptions so that content presented within graphic images on web pages and in documents can be read by screen readers.

How. Users who are unable to see images depend on content authors to supplement their images with alternate text, which is often abbreviated “alt text”. The purpose of alt text is to communicate the content of an image to people who can’t see it. The alt text should be succinct, just enough text to communicate the idea without burdening the user with unnecessary detail. When screen readers encounter an image with alt text, they typically announce the image then read the alt text. Most web, document and LMS authoring tools provide processes for inserting alternate text, and some even present prompts to remind you to do so. For example, when using an LMS to deliver a course, if you upload an image to a content page, you may be prompted to enter alt text for the image. Alt text will not be visible to sighted users, but a screen reader along with a speech synthesizer will read it aloud at the time the image is presented. But what words do you use to describe the image? I suggest that you imagine you are talking by phone to a person who does not have access to the image. What aspects of the image would you describe to this person? That is what the alternate description of the image should include. Make it precise, brief, and not exactly the same as surrounding text already included in the document. For additional guidelines access Accessible Documents.

6. Use large, bold, sans serif fonts on uncluttered pages with plain backgrounds.

Why. Applying this tip will make your content easier for all students to read the content and provide specific benefits for students who have visual impairments, hearing impairments, and reading-related learning disabilities.

How. This tip applies to documents, such as PowerPoint slides, and to materials displayed on the content pages of your LMS. It is also good to make paragraphs short, insert spaces between paragraphs and before titles, and use lists.

7. Use color combinations that are high contrast and can be read by those who are colorblind.

Why. Following this tip benefits students in your course who may have low vision or be colorblind. It also benefits anyone using access devices where color and contrast may be different than what you see on your screen.

How. Inadequate contrast and certain color combinations can make it difficult for some students to view your screen content. Some guidelines follow.

- Make sure there is a high level of contrast between text and backgrounds. Black on white is much better than grey on a white background.

- Avoid making color the only way to convey information. Color-coding should be a redundant means of conveying information "Select the red part of the chart," for example is a useless instruction to someone who cannot distinguish the colors on the page, but "Select the red, striped section of the chart" gives the student two characteristics to look for.

- Avoid color combinations that are known to be difficult for some people to distinguish between, such as red and green. Access the Color Contrast Analyzer and Color Blindness Simulator to evaluate color contrast and simulate different types of colorblindness.

- Use backgrounds that are plain, ideally a solid color.

For additional guidelines access Accessible Documents.

8. Caption video and transcribe audio content.

Why. Captions benefit people who are unable to hear the audio, are English learners, are in a noisy or noiseless location, have slow Internet connections, want to know the spelling of words, and need to search for specific content quickly.

How. Caption your videos offer real-time captioning for audio conferences. Transcribe audio content; For specific instructions for doing so, consult Accessible Videos.

9. Use a small number of IT tools and make sure they present content and navigation that require use of the keyboard alone and otherwise employ accessible practices.

Why. Although you can expect assistive technologies to fully emulate the keyboard, this is not true of the mouse. If an IT developer ensures that navigation and other functions normally undertaken using a mouse can also be accomplished using the arrow keys on the keyboard, users of assistive technology can operate that IT.

Minimize the amount of instruction that is necessary regarding how to use technology in your course, unless learning about this technology is an objective of your instruction. When you consider using technology that is not integrated within the LMS you are using, you can get some idea of its accessibility by looking at the company website. If you find no mention of accessibility features, likely not much attention has been paid to it. You can also seek assistance from disability services or IT staff on your campus, or send a message to a group of knowledgeable people, like those on the ATHEN online discussion list. You can test if the content and navigation of IT you wish to use in your course is accessible with the keyboard alone by setting aside your mouse and trying to navigate it with your keyboard. Consult Accessible With Keyboard for elaboration on this topic.

Instructional Methods

Consult Equal Access: Universal Design of Instruction for a review of the three sets of principles that underpin the universal design of teaching and learning activities. For online learning, you can quickly make progress by with the following tips.

10. Assume students have a wide range of technology skills and provide options for gaining the skills needed for course participation.

Why. It is most important for students to meet the objectives of your course. Unless the content is about IT, try to minimize the IT skills need to simply to access it. Offering students resources to develop necessary skills can minimize the negative impact for students who have difficulty learning to use complicated and likely reduce IT barriers for students with disabilities, especially those using assistive technology.

How. Pay particular attention to skills needed to operate the learning management system you are using in your course. Imagine that at least one student in your class is using it for the first time. In the syllabus or in the first announcement of the course, suggest how students new to the LMS can get up to speed quickly, pointing directly to specific videos and instructions that will help them get started. Also consider providing a written and video tour of the class, where they will find lessons, assignments, etc.

11. Provide options for learning by presenting content in multiple ways (e.g., in a combination of text, video, audio, and/or image format).

Why. Providing multiple ways for students to gain knowledge and skills presented in a course allows students to learn as they learn best and offers accessible options for students with a variety of disabilities.

How. Present content in multiple ways that are each designed in an accessible manner (e.g., a combination of text, video, audio, or image). For example, any LMSs include electronic whiteboards on which instructors and students can share their ideas by writing and drawing on the board. Electronic whiteboards work as graphical tools that operate in real time. Unfortunately, the graphical workspace of a whiteboard is not accessible to students who are blind and using screen readers. If you choose to use a whiteboard in your course, think about how a student who cannot access it can gain the content presented in that manner. Consult with disability services personnel to explore options. Consult the Delivery Methods section of Equal Access: Universal Design of Instruction for guidance on instructional practices that allow students to have choices for learning the content that align with their learning preferences.

12. Provide options for communicating and collaborating that are accessible to individuals with a variety of disabilities.

Why. Simple, asynchronous communication is particularly beneficial for individuals who take a longer time to compose their thoughts or type at a rate that is slower than average, possibly because

- their first language is different than the one in which the course is presented,

- they have a specific learning disability that impacts writing speed,

- they have a condition that impacts social interaction,

- their culture with respect to interactions is different than the communication style of the instructor or other classmates,

- they are new to the technology being used in the course,

- they find it difficult to track multiple threads of conversation that happen simultaneously and with text constantly changing position on the screen, and/or

- they use assistive technology than impacts entry speed.

How. Email and other text-based asynchronous communication, which does not have to occur at the same time, tends to be accessible to most individuals with disabilities. For example, when using email, distribution lists, and discussion boards each student and instructor can read and post messages at his/her convenience. Synchronous communication (e.g., Zoom conferencing), which takes place at an agreed-upon time, can be difficult for some students because of their schedules, disabilities, and communication speeds. When synchronous communication is in audio form only, steps should be taken to ensure that students who are deaf can participate (e.g., work with support staff to arrange for a real-time captioner and work with technology staff to get it to appear on the screen). Since one of the main advantages of taking an online course is the flexibility of the schedule, I encourage instructors to engage in asynchronous communication as much as possible. One idea is to allow the use of synchronous tools for small group work along with other options and require that members in each group reach consensus in choosing the technology they will use for their meeting(s). For example, for a small group assignment in an online learning course, I gave each group a list of tools they could use to interact—standard email, the discussion board in the LMS, a telephone of Internet-based conferencing system, etc. They needed to decide as a group what communication mechanism they would use, ensuring that everyone could "attend" and engage in the meeting, and include as the first item in their group report to me how they made that choice. No group selected a synchronous option (e.g., phone conference), all because they could not find a convenient time for everyone in the group to meet. One group, however, reported that one member of their group disclosed to others that she was deaf and, although she could use a relay service (that would translate her contributions and the comments of others), she preferred one of the asynchronous options. Although the student who was deaf disclosed her deafness to her classmates voluntarily, she didn't need to; she could have just said that a phone conference would be inconvenient for her. Consult the Interaction section of Equal Access: Universal Design of Instruction for guidance on multiple, accessible ways to interact with students and for them to interact with each other and the course content.

13. Provide options for demonstrating learning (e.g., different types of test items, portfolios, presentations, single-topic discussions).

Why. Following this tip gives students many ways to share what they are learning and have learned and instructors a clear picture of the progress of their students and what students have learned in a specific unit or the course overall.

How. Regularly assess students’ progress, provide specific feedback on a regular basis using multiple accessible methods and tools, and adjust instruction accordingly. Monitor and adjust. Assess students’ background knowledge and current learning informally (e.g., through class discussions) and formally (e.g., through frequent, short exams), and adjust instructional content and methods accordingly. Set clear expectations. Keep academic standards consistent for all students, including those who require accommodations. Provide clear statements of expectations for the course, individual assignments, deadlines, and assessment methods. Include straightforward grading rubrics for assignments. Test in the same manner in which you teach. Ensure that a test measures what students have learned and not their ability to adapt to a new format or style of presentation. Allow extended time on tests, unless speed is an essential course objective. Provide sample test questions, exemplary work, and study guides. Consider sharing sample test questions with answers and exemplary work of previous students, discussing how to study for course exams, and providing study guides. Consult the Feedback and Assessments section of Equal Access: Universal Design of Instruction for guidance on offering multiple ways for students to demonstrate their learning.

14. Address a wide range of language skills as you write content (e.g., spell acronyms, define terms, avoid or define jargon).

Why. Following this tip benefits students whose first language is not English and those who have specific types of learning disabilities.

How. Have you heard the humorous saying by an unknown author, "Don't use a big word where a diminutive one will suffice. “Seriously, consider the level of difficulty of the words you use in your lessons. If you are tempted to use a word that might be unknown to some of your students, perhaps because their first language is not English or they have a specific type of learning disability, ask yourself if you can use a word that is more commonly known and still get your point across. Use plain language; define terms and spell out acronyms; and avoid or explain figures of speech, idioms, and jargon. When a word is important to use even though it might be confusing to some students, define it within text and include it in the course glossary. Consult the xx section of Equal Access: Universal Design of Instruction for guidance.

15. Make instructions and expectations clear for activities, projects, discussion questions, and assigned reading.

Why. Following this advice is beneficial to everyone, but particularly to students with learning disabilities and English language learners.

How. Avoid making a huge "content dump" on your students. This can easily happen when you send students to an external website that might have tons of information on a topic. Tell your students what you expect them to do at the site—e.g., read the content in detail and be prepared to discuss it with the group, browse the content so that you know what topics are covered but it is not necessary to read the material in detail, spend 10 minutes at the website so that you know what useful procedures are described in case you need to use them in your course project).

16. Make examples and assignments relevant to learners with a wide variety of interests and backgrounds.

Why. Following this tip will increase the motivation of students with different interests and backgrounds to learn the content and skills presented in the course.

How. Keep in mind the great variety of characteristics that your students may possess, including those related to gender, race, ethnicity, culture, marital status, age, communication skills, learning abilities, interests, physical abilities, social skills, sensory abilities, values, learning preferences, socioeconomic status, religious beliefs, etc. Consult the Class Climate section of Equal Access: Universal Design of Instruction for guidance.

17. Offer outlines and other scaffolding tools to help students learn.

Why. Many students, including those with learning disabilities and challenges with outlines, notes, copy of presentation slides—that help them take notes, prioritize learning concepts, and organize their work.

How. Summarize major points; give background and contextual information and deliver effective prompting. Offer outlines, summaries, graphic organizers, and other scaffolding tools to help students learn. Provide options for gaining background information, and vocabulary. Share glossaries, chapter outlines, study questions, and practice exercises. Give reminders and prompts when referring to content previously presented.

18. Provide adequate opportunities to practice.

Why. Following this tip allows extra practice precisely to the students who need it, without lowering your standards for learning and without requiring more practice than some students need.

How. Consider posting for all students the amount of practice you think should be required of average students and then offering optional additional practice (with problems and solutions) for any students who decide they need more practice.

19. Allow adequate time for activities, projects, and tests (e.g., give details of project assignments in the syllabus so that students can start working on them early).

Why. Following this tip will reduce the chance that your are grading on speed when that is not the main objective of the test or other activity.

How. Strategies to ensure that students have adequate time for activities and projects is to take care in spacing out assignments throughout the course, include complete instructions for all activities in the syllabus so students can plan ahead and organize their time effectively, and give students early access to the course materials and assignments. Similarly, when requesting that students watch a video, indicate how long it is. When asking them to visit a website say for how long and what they should focus on.

20. Provide feedback on project parts and offer corrective opportunities.

Why. Providing feedback on project parts and offering corrective opportunities benefits many students, including those who have difficulties with executive functioning and who come from cultural backgrounds that make it easy for misunderstandings to occur.

How. Offer regular feedback and corrective opportunities. Arrange for peer feedback when appropriate. if you assign a large term project, have students submit their project plan and perhaps some draft parts of the assignment before the final due date. This practice can ensure that students do not go too far afield from your intention for the project.

Accommodations

Since it is likely relatively few students with disabilities will need accommodations if you apply universal design principles to your course. Plan for accommodations for students whose needs are not fully met by the instructional content and practices. This includes knowing how to arrange for accommodations. Learn campus protocols for getting materials in alternate formats, captioning videos, and arranging for other accommodations for students with disabilities. Be sure to tell students how to arrange accommodations on the syllabus.

Final Thoughts

Applying UDHE is not difficult when it is baked into all aspects of the course design from the start. In my online courses I enter instructional content in HTML within the LMS content pages, in part to save students the step of opening an attached document. I use built-in LMS features to provide alt text for images and format lists and hierarchical headings and then insert descriptive hyperlink text. I insert the content of the syllabus within an LMS content page but also offer a version accessibly formatted in Word for students who want to print it or tailor it for their own use by removing content they do need and adding personal notes. With all written content designed to be accessible and videos captioned, no student in my online courses has needed an accommodation for media remediation.

UDI practices can be developed during the process of creating an assignment. As you begin to formulate a design for the assignment, reflect on how it might be inaccessible to students with specific characteristics. For example, in an online course I conceived of an assignment where students would find an image of a space that applied a UD practice but was not labeled as such. Then, in the course discussion board, each student would share the URL or attach the image and state why it is a good example of UD. After that, each student would read the messages posted by classmates and comment on at least one of them. Following is a draft of the assignment.

| Search online for an image that is an example of a feature of a space that is an application of UD but is not labeled as such. On the course discussion board share the URL or attach the image and state why it is a good example of UD. Then read the messages posted by your classmates and reply to at least one of them. |

To whom might this draft assignment be inaccessible? Clearly, (1) finding and describing the image and (2) accessing the content of images presented by classmates would not be accessible to a student who could not see images, perhaps because of blindness or because of a very slow internet connection. I addressed both of these issues as I created the final assignment described next. I have bolded the text added to address the two potential access issues I identified.

|

Search online for an image that is an example of a feature of a space that is an application of UD but is not labeled as such. On the course discussion board share the URL or attach the image and state why it is a good example of UD. Describe the image enough so that someone who cannot see the image can understand the point you are making. Alternatively, describe a feature of a space you are aware of that is a good example of UD and explain why it is a good example. Then read the messages posted by your classmates and reply to at least one of them. |

I have offered this assignment multiple times. Although several students have used the alternative assignment, I do not know why. If any of these students were blind, they would not have needed to disclose because all of the materials and methods I use in the courses are fully accessible. What I do know for sure is if I had used the draft version of the assignment, if a student who is blind enrolled in the course, that student would have needed to request an accommodation.

Resources and Acknowledgment

In this module I shared definitions, a framework, and concrete practices for beginning to make your course accessible to and inclusive of students with disabilities. There are many comprehensive resources that share accessibility checkers, elaborate on legal issues, share detailed technical guidelines, provide vendor-specific information, and document promising practices. You will find many of them on the home page and in the Resources section of the AccessDL website.

The content of this instruction is a product of the AccessCyberlearning 2.0 and AccessINCLUDES projects (Grant #DRL-182540, #HRD-1834924, respectively). Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the editors and authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NSF.

Copyright 2020 University of Washington