November 4, 2010

UW losing 60-year tradition of salmon returning to campus

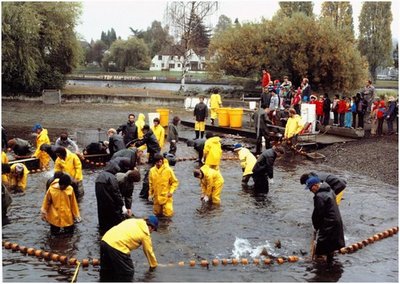

New directions in fisheries research, along with budget cuts, led the UW’s School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences faculty to decide to discontinue the research salmon run created some 60 years ago at the campus. Gone will be the decades-long tradition of salmon returning to campus each fall, just as the students do.

Ending the run will take place during the next four autumns as young salmon released each spring from 2006 to 2010 grow to adult size in the open ocean and return to the pond located next to Portage Bay, behind the UW Medical Center. These returning salmon will not be spawned so no more young salmon will leave the UW to grow in marine waters.

The UW run currently numbers between 1,500 and 2,000 salmon. Issaquah’s hatchery, in comparison, has returns of 10,000 to 20,000 fish. At the UW the run is about 80 percent chinook and 20 percent coho salmon. In the past, fish that returned to the UW pond would be artificially spawned, the eggs incubated in the hatchery and young fish released in the spring.

“The school intends to continue a variety of freshwater programs at the hatchery facility, including salmon research, but will obtain fish from other sources,” said David Armstrong, director of the School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences. “The expense of maintaining the run in the face of repeated permanent state budget cuts could not be justified, given that there are less expensive alternatives that still provide research and teaching opportunities for faculty and students.”

Savings in four years, once the run is eliminated, will be approximately $58,000 a year.

Classes for students interested in careers in fisheries management are no longer conducted using the pond or fish run, as they once were. Currently the UW hatchery is supplying eggs and young fish to a couple federal fisheries research groups, and ending the run may disrupt the data sets they’ve been building, but no UW faculty member has used the run since 2005.

Still, there’s a large body of published work by UW faculty past and present based on findings from the run and hatchery.

Fish returning to the pond were routinely weighed, measured and notes taken on such things as their ages, egg size and potential to produce abundant offspring. UW professor Tom Quinn found funding in the early 2000s to pull together all that data that had been committed to paper, computer punch card and digital records over the decades.

“My colleagues and I wrote four papers looking at the long-term trends in survival, growth, age at maturation and return timing of the run,” Quinn says. They looked at such things as whether releasing smolts when they were larger increased their chances of survival — it did not — and if years of preferentially spawning the first-returning salmon leads to runs that return early — it does. The latter is particularly interesting, Quinn says, because the advancement in timing came in the face of increasingly warm fall water temperatures, which favors the fish that arrive later in the year.

“I am trying to publish two more papers,” Quinn says. “These were studies that 30 years ago Ernie Brannon conducted, one of them with my help. Both involve experimental groups of chinook salmon released from the UW hatchery and I am looking at patterns of migration. One was a hybrid cross between UW and Elwha River salmon. I doubt that such an experiment would even be permitted today so it is important to go back and look at those data.”

Part of what’s being lost is that ability to manipulate a run for experimental purposes, said Jon Wittock, hatchery manager. The intention of most state and federal hatcheries is to bolster runs for conservation or fishing. Consequently, the managers of those hatcheries may be reluctant to let scientists alter the way some young fish are raised in order to study the effects of, say, higher water temperatures on the survival of the fish.

Further back, the UW run and hatchery were used for such things as studying salmon olfactory and homing abilities, work done by Brannon and then-grad-student Quinn, as well as investigating genetic variation, research done by Bill Hershberger.

The run of salmon was started in 1949 and the fish pond completed in 1961. The idea for the run came from Lauren Donaldson, who joined UW fisheries program 1932. After WWII, war department researchers who were concerned about the effects of nuclear weapons testing over aquatic environments asked Donaldson to consider the effects on salmon. That work would “be greatly facilitated if the fish were cooperative enough to return to the university,” Robert Stickney, former director and author of a book on the history of UW fisheries, wrote about Donaldson’s impetus to start the run.

“As many of us know, salmon spawn in the gravel of streams. They find their home stream by detecting the characteristic odor of the water in which they hatched,” Stickney wrote. “Detractors, many of whom undoubtedly thought Donaldson was a candidate for a rubber room, were, to say the least, skeptical that the fish could survive the trip past the polluted areas [polluted because of heavy industrialization] and through the locks and, once the fish reached the campus, there was no stream for them to climb.”

Undeterred, Donaldson made plans to pump lake water through the hatchery and release it into Portage Bay, as a way for the hatchery fish to find their way back, as well as erecting a fish ladder. He released 23,000 chinook fingerlings into Portage Bay in 1949. In 1953, 23 adults jumped up the fish ladder and entered the raceway as four-year-old adults.

In 1989, when his book was published, Stickney wrote, “Fisheries professionals from the globe over pass through Seattle in an almost continuous stream. Many of them visit the School of Fisheries, and most are interested in viewing the return pond to observe, if their time is right, the spawning activity. ‘So this is the pond made so famous by Dr. Donaldson,’ is the familiar statement.”

There’s also been a traditional autumn trek of school teachers and their classes to the pond to learn about the life cycle of salmon and watch the fish being spawned, which has been cancelled this year. Last year about 30 students visited.

That’s down from 3,000 in the early 2000s when Seattle City Light was providing most of the funding for what was called the “Salmon in the Classroom” project. When Seattle City Light stopped paying its portion, the fisheries faculty decided to discontinue the program because of the cost and partly because of concerns by some faculty that youngsters might get the idea that fish from hatcheries is an acceptable alternative to protecting habitat so natural runs can thrive, although the school kids were always informed about the difference when they visited.

In the wild, salmon die naturally after spawning. As part of the artificial spawning conducted at the pond all these years, the adult fish were first killed so that eggs and milt could be collected. The fish are killed in a humane fashion following protocols accepted by the UW’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. To end the run, the fish will be killed but no eggs or milt will be collected. Fish that are ready to spawn are generally not good to eat and, as in past years, the carcasses will go to a composting facility.

Wild fish in area streams could be harmed if fish from the UW’s run were to start competing with them for spawning sites or intermingle with them, which is a reason the fish need to be eliminated and not left to stray into other waterways.