May 7, 2009

British group Radiohead inspires staffer to write

Jody Tate was busy earning his doctorate in English from the UW when he heard Radiohead’s Kid A album, released in 2000. He loved it, started writing about the popular, iconoclastic British rock group, and hasn’t stopped.

“I was deep in graduate school and the album fascinated me,” said Tate, now 35 and a web developer for Network Systems. “It was like nothing I had ever heard. But the more I listened, talked with others and read about the album, I found out the sounds weren’t new — just new to me.” Once he realized their work had roots in other musical styles, “I followed down every lead I could.”

Plus, he said, “I had already picked up these research skills in graduate school, and it seemed a nice way of procrastinating. So instead of working on Shakespeare, I turned to Radiohead for a year and a half.”

Increasingly interested, Tate even lectured about Radiohead during a travel fellowship to France in 2001. He later turned that lecture into an essay on the group that got published in 2002 in Post Modern Culture, a journal put out by Johns Hopkins University. The essay was titled “Radiohead’s Antivideos: Works of Art in the Age of Electronic Reproduction.”

School chums in England, the members of Radiohead formed the alternative band in the early 1990s, led by songwriter Thom Yorke and guitarist Johnny Greenwood. After releasing a hugely popular single called “Creep” in 1992, the band’s profile rose with its Pablo Honey album the next year. Increasing attention came with The Bends, their well-reviewed 1995 album. But OK Computer, the group’s 1997 release, rocketed them — for both good and ill, Tate writes — into the realm of global superstardom. The British magazine Q ranked OK Computer as the single best album ever made.

Tate traveled to England on an American Embassy grant to lecture on Radiohead in 2005. Intrigued by the nature of discussion about this moody, darkly creative force in modern music, he put out “a standard CFP, or call for papers” with the aim of editing a book on the group.

He got about 30 legitimate submissions. He said, “The toughest part was just figuring out which essays went together the best, and commented on each other.” And, of course, he got some less academic replies — one essay, he said, pontificated on “why Radiohead is a badass group.”

The resulting book, The Music and Art of Radiohead was printed in 2005 by Ashgate Publishing. One Amazon.com reviewer called the book “well-written and an overall fantastic attempt to further understand the enigmatic peculiarity that is Radiohead.”

After that, Tate wisely decided to complete his doctorate, but his interest in Radiohead continued. He watched over the years as the group and its titular leader Yorke battled the stresses that come with fame and the demands of their record label, EMI, with whom they later parted company. He said his favorite album by the group is Amnesiac, which followed Kid A in 2001.

Radiohead commanded headlines worldwide when the group decided to release its 2007 album, In Rainbows, direct to fans over the Internet without a record corporation as middleman. Tate quite likes this album, too. “I can’t seem to listen to it loud enough,” he said.

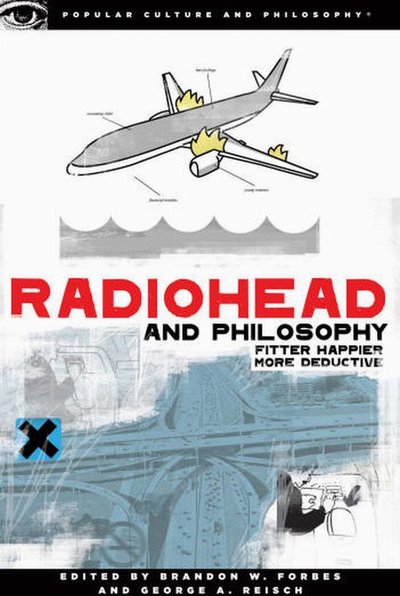

Last year, Tate was asked to once again write about his favorite group — this time for an upcoming book to be titled Radiohead and Philosophy.

He wrote an essay pondering the group’s successful — some even say groundbreaking — break from record company exploitation and dependence. Making use of a remark by Yorke likening record companies to “blood-sucking vampires,” Tate compared Radiohead’s anti-capitalism to that of Karl Marx. He titled his essay “We Capitalists Suck Your Young Blood.” The book is being published this year.

“This essay was more fun to write,” he said. “This book was not meant for an academic audience — it was meant for people who know Radiohead and want to know more about philosophy.” Another in the series, he said, was Seinfeld and Philosophy.

Of Radiohead’s decision to sell straight to consumers, Tate said, “It wasn’t their idea to change the music industry, but that’s what people said about it afterwards. They just thought it would be a fun thing to do.” And if fans like Tate are any measure — he chose to buy a deluxe, collectors version of In Rainbows online for 80 pounds — the band still made money even without corporate help.

Did Radiohead help break the music industry? “I’d probably argue yes, but it was also already falling apart,” Tate said.

And for good enough reason, many would say. Tate’s essay describes the stress Yorke and band mates felt when record company expectations rose along with the band’s star. “You could see increasingly in interviews with the band, as soon as they got the record contract that became a pressure that increased year after year,” he said. “They didn’t know how to handle that.”

Tate described how through this evolution Radiohead began to find its way again. The result was a more “human-sounding” album than its predecessor, their less-praised 2003 release Hail to the Thief. The band, and notably Yorke, seem renewed, Tate wrote. “To borrow from Marx, their working lives have reverted to lifetimes, where work is enjoyment.”

Tate is glad for them, and ready for more. “As long as they keep making albums I will probably keep writing about them,” he said. He maintains a blog on the group at pulk-pull.org.

But does all his intellectual analysis dampen his enjoyment of the music? Tate recalls a quote from a band member saying people shouldn’t “twiddle their goatees” over its music and just enjoy it. Tate, though goateed himself, isn’t worried.

“There is some sense that people think, oh, this is killing it. But the music still stands up,” he said. “And even now, when I get in the car I still turn it up probably too loud.”

“I don’t think you could do one without the other,” he said.