March 5, 2009

Lights and landscape: UW profs to discuss design of Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition

With the flip of a switch June 1, 1909, thousands of electric lights illuminated the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition on what’s now the UW campus. The fair became an oasis of light in a city that at night was largely dark. Those electrical lights were also part of a carefully conceived design that helped make the exposition a success, and gave permanent shape to the University.

Four professors and a doctoral student in the UW College of Built Environments will explain the design of the exhibition and implications for both the city and the University at “Meet Me at the Fair,” a conference this Friday and Saturday, March 6-7 at the Museum of History & Industry. It’s part of a series of events marking the centennial of the exposition, which itself attracted some 3 million visitors in five months.

“It was an explosion of light, which was crucial to the fair’s success because people could come in the evening after work,” said doctoral student Tyler Sprague in a phone interview.

“From the illuminated dome of the U.S. Government building to the tumbling cascades lit from under water,” Sprague writes in an abstract for his talk, “lighting was both a technical triumph and a significant aesthetic display.”

But lighting is only part of the story.

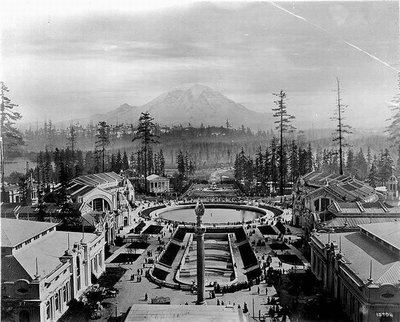

The exposition enabled landscape architect John C. Olmsted to show the Pacific Northwest the value of well-designed public open space. A partner in Olmsted Brothers, the family firm that introduced landscape architecture to America, Olmsted had already planned various works for the Seattle Parks Board and the UW, but little that embodied his vision for the city had been built. Thaisa Way, an assistant professor of landscape architecture, will explain how Olmsted designed for the exposition landscape a formally organized central space featuring expansive views of mountains, lakes and trees.

Until the fair, Mount Rainier hadn’t been a focus of campus planning, writes Jeffrey Karl Ochsner, an architecture professor who will speak at the conference, which is sponsored by the Pacific Northwest Historians Guild. The legacy of the exhibition, Ochsner says, is the planning framework for the campus — reshaped topography plus plantings, fountains and walkways — that remained after almost all Exposition buildings had disappeared.

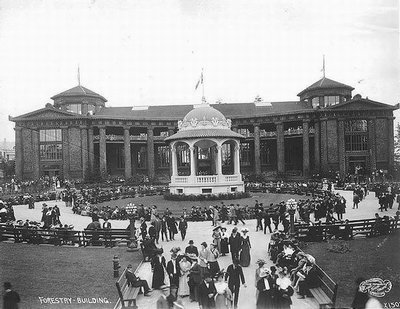

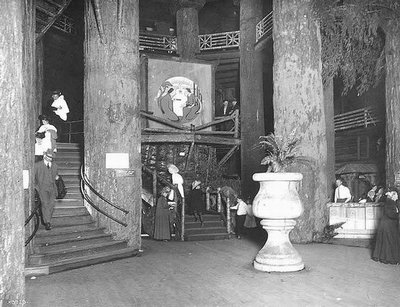

The Forestry Building was one that didn’t endure, even though considered the most striking at the fair, Kathryn Rogers Merlino writes in her abstract. An assistant professor of architecture and architectural history who researches best ways to adapt and reuse everyday structures, Merlino will talk about the Forestry Building at the conference.

Modeled after a Greek temple, Forestry was made of single, unpeeled logs of old-growth fir — some as much as five feet in diameter — to reflect the abundance of timber in the Pacific Northwest. Problem was, the logs weren’t treated to prevent dry rot and infestation, so in 1930, the building had to be taken down.

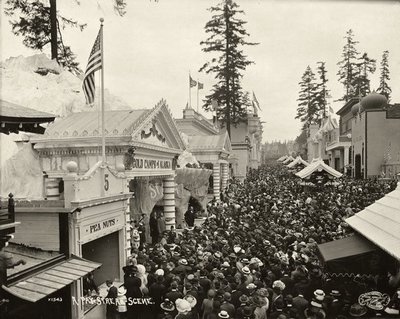

The Pay Streak, the amusement area of the fair, contrasted with serious exhibits in the main section, but reflected late 19th and early 20th-century social values. It was named after lines of ore over the bedrock of Alaskan creeks, where the richest deposits usually concentrated. According to Manish Chalana, an assistant professor of urban design and planning who will also speak at the conference, the Pay Streak perpetuated certain notions about Western superiority. For example, a group of thatched huts and people in them were billed as the “Igorrote Village: Great Exhibit of Wild People from the Philippine Islands.”

The Pay Streak, Chalana writes at the end of his paper, “communicated the very same message of Western social and industrial progress that was the Exposition’s whole raison-d’etre, under the guise of pure entertainment.”

For more information about “Meet Me at the Fair,” go to http://www.pnwhistorians.org.