The genome of the evolutionary ancestor of humans and present-day apes underwent a burst of activity in duplicating segments of DNA, according to a study to be published in Nature Feb. 12, the 200th anniversary of Charles Darwin’s birthday.

“The new study shows big differences in the genomes of humans and great apes within duplicated sequences containing rapidly evolving genes. Most of these differences occurred at a time just prior to the speciation of chimpanzee, gorilla, and humans,” said University of Washington researchers Tomas Marques-Bonet and Jeffrey M. Kidd who headed the study. Both are fellows in the lab of Evan Eichler, UW professor of genome sciences, a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator and senior author of the paper.

“It is unclear why, but the common ancestor of humans, chimps and gorillas had an unusual activity of duplication,” Kidd added. “Moreover, we don’t yet know the functions of most of the genes that were affected by these duplications.”

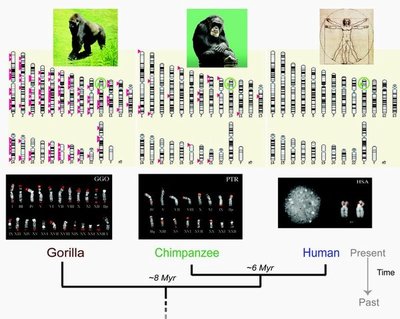

The great ape ancestors, from whom humans, gorillas and chimps descended, lived in Africa between 8 million and 12 million years ago. Most scientists think that the lineage that eventually led to chimps and humans diverged from the African great ape ancestors about 5 million to 7 million years ago.

“What’s exciting for us to learn,” Eichler added, “was that sequence duplication acceleration occurred in an era when other types of mutations had slowed within the hominid (human-like) lineage.”

“There was significant increase in genome activity in both the number of duplication events and the number of base pairs of DNA that were affected,” Marques-Bonet noted.

The results suggest that evolutionary properties of copy-number mutations, such as repeated segments, differ from other forms of mutations.

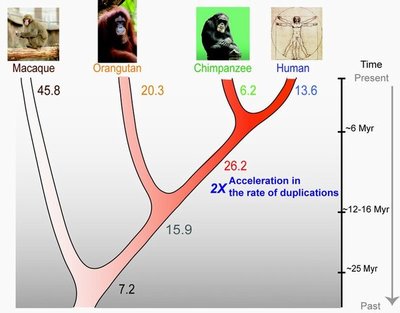

To understand the pattern and rate of genomic duplication during evolution, the researchers constructed a map of segmental duplications for four primate genomes: macaque, orangutan, chimpanzee, and human. They then compared the duplications across the four species. They characterized a duplication as shared if it occurred in two or more of the four species and lineage-specific if it was found in just one species. A small fraction of the duplicated content was human-specific, while the major part of duplications was shared with the other species.

“Our team found striking examples of recurrent duplications of DNA segments that happened independently in different lineages,” the researchers said. “Most of the shared duplications were already present in the chimp-human common ancestor, but these are highly variable in copy number between and within human and great ape species.”

Scientists have had difficulty determining why humans and chimps differ so much at a physical and behavioral level but are genetically so similar. Chimps and people share almost 99 percent of the non-duplicated sequences of their genomes; their proteins are virtually identical; and there are very few rearrangements that distinguish ape-human chromosomes. In contrast, the researchers noted that the duplicated sequences show much more variation than the other portions of the genetic code.

“There is still no final answer as to why chimps and humans are different,” Marques-Bonet and Kidd said. “Maybe segmental duplications that are specific to humans are another layer to explore, or maybe the distinction between human and chimps is not found in these genetic differences.

“What is certain is that genetic differences contribute significantly to what makes a human and chimp different, and we know that these regions of our genetic code are changing much more rapidly than most others. The next challenge will be making sense of all these differences and the genes that are affected by them.”

Co-authors on the Nature article, “A burst of segmental duplications in the genome of the African great ape ancestor,” in addition to Marques-Bonet, Kidd, and Eichler, were Mario Ventura and Maria Francesca Cardone, both of Sezione di Genetica-Dipartimento di Anatomia Patalogica a Genetica, University of Bari, Italy; Tina Graves, LaDeanna W. Hiller, Lucinda A. Fulton, Elaine R. Mardis, and Richard Wilson, all of the Genome Sequencing Center at Washington University in St. Louis; and Ze Cheng, Zhaoshi Jiang, Carl Baker, Ray Malfavon-Borja, Can Alkan, Gozde Aksay, Santhosh Girirajan, Priscilla Siswara, and Lin Chen, all of the UW. Marques-Bonet and Arcadia Navarro have an affiliation with the Institut de Biologica Evolutiva, Barcelona, Spain.

The National Institutes of Health funded the research.