May 27, 2010

Flexible approach to anxiety treatment may result in better symptom relief

People with anxiety disorders showed a greater relief of symptoms and a better ability to function when their primary-care physicians used a flexible approach to treatment, according to a UW-led study.

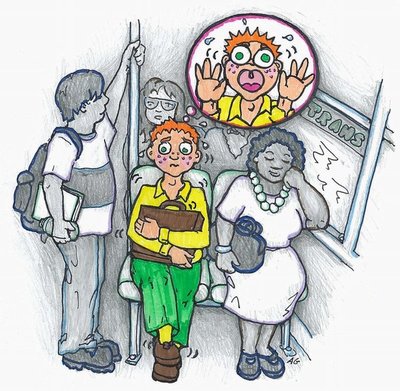

The study looked at the four most common anxiety disorders: panic attacks, generalized anxiety, social anxiety, and post-traumatic stress.

Patients who were given a choice of cognitive behavior therapy, medication, or both, along with computer-assisted treatment support, had a response rate of more than 63 percent. Patients treated with usual care had about a 45 percent response rate.

The flexible approach resulted in a remission rate at one year of more than 51 percent, compared to about 33 percent for usual care. The advantages of the flexible approach seemed to persist for at least a year.

Dr. Peter Roy-Byrne, UW professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, and his colleagues conducted the study, which is published in the May 19 Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA). Roy-Byrne is a researcher, teacher and psychiatrist at UW Medicine’s Harborview Center for Healthcare Improvement for Addictions, Mental Illness and Medically Vulnerable Populations, which goes by the acronym CHAMMP.

The study looked at ways that primary-care practices could improve the provision of commonly used strategies for anxiety disorders, rather than testing new therapies. The researchers called the approach CALM, for Coordinated Anxiety Learning and Management.

“Improving the quality of mental health care requires continued efforts to move evidence-based treatments of proven efficacy into real-world practice settings with wide variability in patient characteristics and clinician skill. The effectiveness of one approach, collaborative care, is well established for treatment of depression in primary-care practices, but has been infrequently studied for anxiety disorders, despite their common occurrence in primary care,” the authors write.

The CALM intervention included real-time web-based outcomes monitoring to optimize treatment decisions. It also had a computer-assisted program to optimize the cognitive behavioral therapy provided by non-expert care managers. The care managers also assisted primary-care clinicians in promoting adherence and optimizing medications.

“In this way, CALM seeks to accommodate the complexity of real-world clinical settings, while maximizing fidelity to the evidence-base in the context of a broad range of patients, clinicians, practice settings, and payers,” the authors noted.

The randomized controlled effectiveness trial of CALM compared with usual care took place in 17 primary-care clinics in four American cities. Between June 2006 and April 2008, 1,004 patients, ages 18 to 75 years, were enrolled.

The patients in the study had one or more of four anxiety disorders addressed by the CALM model. More than half of the participants had two or more anxiety disorders and two or more chronic medical conditions. Two-thirds of the participants also had major depression.

They subsequently received treatment for 3 to 12 months. Follow-up assessments at 6,12, and 18 months after the beginning of the trial ended in October 2009. Anxiety symptoms were measured with the 12 item Brief Symptom Inventory.

The researchers found that the scores on measures of anxiety symptoms were significantly lower for patients in the intervention group at 6 months, 12 months and 18 months.

“The clinical effectiveness across a range of patients and clinics suggest that the CALM treatment delivery model should be broadly applicable in primary care. However, implementation of this model will require reimbursement mechanisms for care management that are not currently available,” the authors wrote.

The CALM model “fits primary-care clinician preferences for interventions that have the capacity to address a range of common mental disorders rather than just one,” the researchers noted. Patients who have more than one psychiatric disorder at the same time are the rule rather than the exception, both in the general population and in clinical practice,according to the researchers.

In addition to Roy-Byrne, the researchers on the study were Michelle G. Craske, Raphael D. Rose, and Alexander Bystritsky, all of the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California-Los Angeles; Greer Sullivan and Mark J. Edlund, both of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences; Ariel J. Lang, Denise A. Chavira, Laura Campbell-Sills, and Murray B. Stein all of the Univeristy of California San Diego; Stacy Shaw Welch of the UW; and Daniela Golinelli and Cathy D. Sherbourne of the RAND Corporation.

The research was supported by grants to Roy-Byrne, Craske, Stein, Sullivan and Sherbourne from the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health.