May 6, 2010

UW medical historian James Whorton traces criminal and environmental poisoning in ‘The Arsenic Century’

The Arsenic Century by UW medical historian Dr. James C. Whorton weaves slander, intrigue, vanity, avarice and public health into a vivid story about “the poison of poisons” in the 1800s. Whorton is professor emeritus of bioethics and humanities in the School of Medicine.

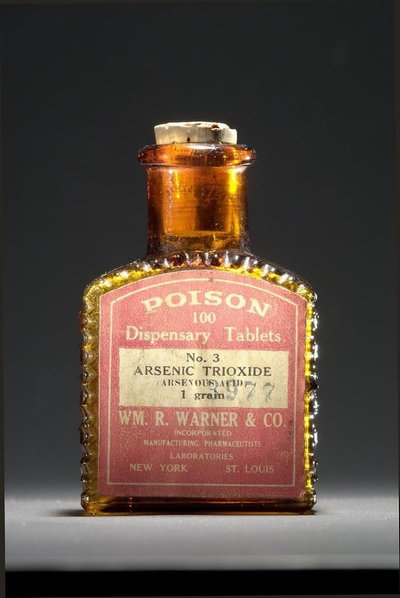

Subtitled How Victorian Britain was Poisoned at Home Work and Play, the book puts arsenic center stage as the villain who was difficult to escape. The bad actor was not the innocuous element arsenic, Whorton explained, but the compound arsenic trioxide. The compound was cheap and easily obtained for rodent control. It had no taste, resembled common kitchen ingredients like flour or sugar, and mixed evenly with food or drink. A small amount did the job. By the time a victim noticed a gritty texture upon swallowing, it was often too late.

Foul play was suspected if remains did not decompose in the grave, because arsenic poisoning could preserve the corpse. Yet, until the 1830s, Whorton said, there was no reliable forensic test for arsenic. In addition, ingestion was not the only route for poisoning: it could kill by inhalation and by contact with other orifices and breaks in the skin. To make criminal accusations even harder to prove, arsenic was incorporated into many medications, cosmetics, and fashionable dyes for clothing and household items. Arsenic poisoning also mimicked deadly diseases like cholera and dysentery. The difficulty in determining guilt meant murderers went free and innocents were hanged. Inquests, Whorton noted, often took place in a pub. Trials following an indictment would be held in courtrooms, with verdicts often handed down in a matter of minutes.

In the macabre comedy Arsenic and Old Lace, two charming spinsters send male visitors to their final reward with a home-brewed concoction. It was actually cyanide and strychnine that hastened their demise. Fatal arsenic poisoning is neither quick nor tidy, Whorton’s book tells of “fireballs consuming the entrails,” and of unrelenting retching and purging that went on for days. “Such an instrument of death and agony” was arsenic’s ghastly reputation.

Among the gruesome uses for arsenic in Victorian Britain was in ridding oneself of unloved husbands and unwanted children. In some cases, penniless mothers believed they were saving their offspring from constant hunger and sure starvation. Motives were not always that compassionate. As burial societies grew to help members avoid the paupers’ mass grave, Whorton said, impoverished parents would register children and then poison them. After a cheap burial, the parents would net a profit.

From pure greed, or simply to survive in a competitive business, many Victorian confectioners would adulterate candies with arsenic to tantalize shoppers. The chemical turned confections an appealing bright green. A pinch of the ingredient was usually too small to kill outright, but a candy habit could cause chronic health problems and a lingering death.

“One of the most disturbing discoveries in my research was how cavalier candy-makers were in using poison to increase their profits,” Whorton said. Others who suffered at the hands of commerce and fashion were the workers who made artificial flowers for the ornate ladies’ hats of the period, candles, the green wallpaper that was in high demand, and Paris-green ball gowns. Arsenic compounds provided the green dye. Purchasers, Whorton noted, were bringing the poison into their homes and social gatherings. Chronic arsenic poisoning became common among high society. In melodramas, “going into the green room” was tantamount to falling sick.

Whorton’s book also covers the seemingly paradoxical use of arsenic compounds in products supposedly created to help people feel and look better. Arsenic was used in medications, cosmetics, and as a strength booster. In that era, accidental death from arsenic, Whorton said, was far more prevalent than intentional harm. Later, advances in toxicology made the substance less attractive to those wishing to hide their murderous intents.

As is often the course with public health threats, Whorton said, gradual awareness of the problem and citizen action eventually resulted in prohibitions and safeguards limiting the use of arsenic during the later part of the 19th century. Britain, with its belief in freedom, was slower than the Continent to do so. Whorton pointed out that another early lesson in environmental health was the difference in people’s reactions to the presence of a toxin, a phenomenon that ecogeneticists now explore.

A few years ago arsenic compounds were still found in wood treated to withstand destruction by insects, until such use was banned. Arsenic continues to contaminate soil near smelters and mines, and is detectable in water supplies in some parts of the developing world.

Whorton became interested in the story of arsenic in the 19th century as a graduate student in the history of science at the University of Wisconsin, where he started researching pesticides and public health in pre-DDT America for his book on the subject, Before Silent Spring, published in 1974. He returned to the topic as a UW professor emeritus. He noted that he received a great deal of assistance with researching the book from UW health sciences librarians, who helped him locate old, obscure documents, materials and drawings.

Whorton’s other books include Crusaders for Fitness: The History of American Health Reformers (1982), Inner Hygiene: Constipation and the Pursuit of Health in Modern Society (2000) and Nature Cures: The History of Alternative Medicine in America (2002). He has written many scholarly articles and has given invited lectures on the history of medicine and public health, the history of health beliefs and behaviors, disease in history, and on how alternative and complementary medicine, like naturopathy and homeopathy arose.

The Arsenic Century: How Victorian Britain was Poisoned at Home Work and Play, was published this spring by the Oxford University Press.