November 8, 2007

UW physician Nassim Assefi publishes debut novel

To take care of the sick. To give aid to those who cannot help themselves. To help people. These are some of the reasons you might hear when you ask someone why they went into medicine.

For Nassim Assefi, her strong desire to help others led to her walking away from the medical field.

Assefi was working on a burgeoning career as a woman’s health physician, having earned her medical degree at the UW School of Medicine and completed her residency training at Harvard Medical School’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. After her training, she returned to Seattle to work at Harborview Medical Center, where she did her first clinical rotation as a third-year medical student.

She had realized her life’s goal — working in the incredible community of Harborview, which Assefi calls “the most special place” she has ever worked. The hospital’s commitment to providing first-class care to all patients, whether rich or poor, reflected her own ideals of social justice and devotion to vulnerable people.

And then, in 2003, came her trip to Afghanistan under the sponsorship of the American Medical Women’s Association. In her work in the Harborview Women’s Clinic, Assefi had treated terrible injuries and worked with patients shattered by trauma here in the United States and abroad.

“I had in been in touch with terrible tragedies through the lives of my patients,” Assefi explained. “But nothing prepared me for Afghanistan.”

The country’s infrastructure had been utterly destroyed by 23 years of war, including the latest round between the Taliban and the U.S.-led coalition forces. Life expectancy was only 42 years, and the lifetime chance of dying from pregnancy was astronomical — about 1 in 7.

Assefi began to understand that as a women’s health expert, she was in a position to help in Afghanistan. Her parents were from Iran and she had worked in Iran after college, so she had some knowledge of the Afghan culture and religion, and could pick up the language pretty quickly.

“I felt like I couldn’t not go,” she said. And just like that, she took a break from her practice at Harborview to help rebuild women’s health care in Afghanistan.

Being a doctor is an empowering experience — being able to save a person’s life can give a person a very special perspective. But in Afghanistan, Assefi realized that her powers as a physician were quite limited by the humanitarian disaster unfolding around her.

“Doctors are supposed to be these saviors, these quasi-gods who can save lives,” she said. “Working in the developing world, you realize that whether someone lives or dies is much less about their access to a doctor and much more about the social determinants of health — food, clean water, education, human rights, basic infrastructure.”

Her experience in Afghanistan did more than just show Assefi how powerless doctors can be in the face of war and destruction. It also helped her realize the importance of preventing that devastation in the first place. That’s when she decided to work towards a different life goal — one aimed at helping people gain a better understanding of each other and reducing conflict between different groups.

“It was in this work that I realized the most powerful thing I could do was not necessarily to be a doctor, but to tell stories about misunderstood parts of the world,” Assefi said. “As someone who was born and raised in America and understood something about the cultures of the Middle East and Central Asia, I felt like I could help build a bridge between cultures.”

Assefi had taken up writing already — being trapped in Indonesia due to a monsoon left her with so much spare time that her patients’ stories began “bubbling up” out of her and onto the page. She had written a chapter for This Side of Doctoring, a collection of essays from women in medicine.

This time, however, her writing would have a different purpose.

When one country is about to invade or wage war against another country, Assefi argues, there seems to be an effort to spin that country’s image as an “evil” nation, or as a place that needs to be liberated. Here in the United States, many people have simple, one-dimensional images of countries like Iraq, Iran, or Afghanistan.

Assefi wanted to help people better understand those countries, by writing compelling stories about people there and showing how they have many of the same hopes and fears as Americans.

“The more we know about another country, the less likely we are to invade them,” Assefi said.

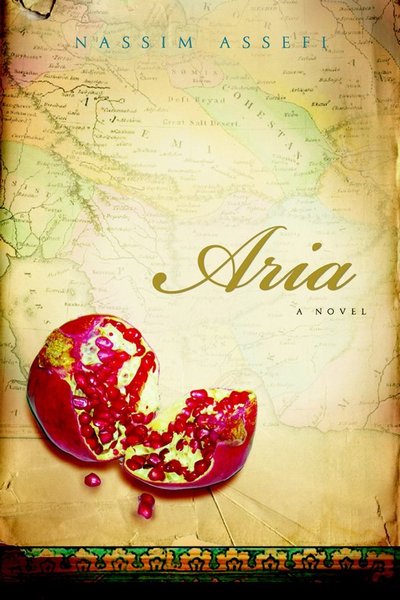

Out of that desire came Assefi’s first novel: Aria. The book tells the story of how Jasmine, an Iranian American woman working as a cancer specialist in Seattle, deals with the sudden death of her only child, Aria, in a car accident. The shattering loss leaves Jasmine searching for meaning, and spurs her into leaving her life in Seattle to travel the world and reconnect with her heritage in Iran.

Though many first novels are autobiographical, this book is not, Assefi said — she has never had a child, and her opinion of her home country of Iran is very different from Jasmine’s.

“This book grew out of the experiences of my patients, especially the immigrants and refugees who had been through war,” she said. “That kind of suffering is hard for people in our country to understand. My book is about what maximum loss looks like in a privileged country like the U.S.”

Building readers’ understanding of terrible loss — and of the cultures that many Americans fear or dislike — could go a long way to bridging the gap between the Western World and war-torn countries in the Middle East and South Asia. Being on a national speaking circuit as a published novelist has also given Assefi a chance to speak out about global health disparities, women’s rights in the Middle East, the impact of war on public health, and other issues important to the developing world.

“Right now, in these fragile times, I may be able to have more impact as a writer than as a doctor,” Assefi said. “Telling stories with authenticity and experience can change the world by bringing us closer together.”