January 22, 2004

New Jacobsen Observatory links two staples of astronomy at UW

New Jacobsen Observatory links two staples of astronomy at UW

It took 109 years, but the second-oldest building on campus finally has a name of its own.

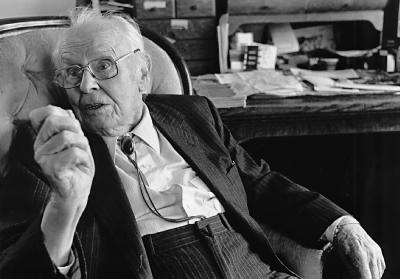

The Board of Regents last week agreed to formally name the astronomical observatory at the north edge of campus the Theodor Jacobsen Observatory in honor of the man who for more than 35 years was the only person teaching astronomy at the UW.

Jacobsen died last July at the age of 102, four years after publishing a book, Planetary Systems from the Ancient Greeks to Kepler, that he had worked on since his retirement in the early 1970s.

The observatory was built in 1895 — six years before Jacobsen was born and 33 years before he came to the UW — from sandstone left over from construction of Denny Hall, the first building on campus. For many years, the observatory dome rotated on surplus Civil War cannon balls. The six-inch refracting telescope, built in 1891, is still used today for public viewing.

In a 1999 interview, Jacobsen said his interest in astronomy started at the age of 7 when he received his first telescope as a gift from his parents. It consisted of a 2-inch lens inserted into a paper tube and was replaced three years later by a metal telescope with a 3-inch lens.

In 1914, Jacobsen’s parents moved their family from Denmark to San Jose, Calif. He graduated from Stanford University and became a Lick Observatory Fellow at the University of California, Berkeley, remaining for two years after receiving his doctorate in 1926. It was at Lick that he began his lifelong astronomical specialty — taking spectroscopic measurements of the four brightest Cepheid variables, stars a few-hundred light years from Earth, all visible with the naked eye. The stars are called variables because their brightness and size continuously increase and ebb.

In 1928, Jacobsen came to the UW as an assistant professor of astronomy and mathematics. A decade later he became a full professor and “executive officer” of astronomy.

For many years he kept an office in the observatory near the Burke Museum, though even back then the observatory was primarily for student use and public demonstrations. City lights have increasingly made it difficult to use the observatory’s telescope for scientific purposes.

Jacobsen said the only device in the observatory that he used regularly was a special-purpose telescope called a meridian instrument, which he used to determine the time from stellar observations for his course in practical astronomy.

He typically taught two courses per quarter, with anywhere from 20 to 45 students in each. “If there weren’t enough students for two courses, they gave me a section of trigonometry or elementary mathematics to teach,” he said.

Jacobsen was the sole member of the astronomy faculty for 37 years, until 1965, when George Wallerstein and Paul Hodge arrived as astronomy professors and Wallerstein became department chairman. In 1971, Jacobsen assumed emeritus status and began work on setting down some of the basic history of astronomy, which resulted in the book published in 1999.