April 29, 2001

UW professor helping create digital replicas of Michelangelo’s sculptures

An exhausted, yet exhilarated, Brian Curless recently returned from Florence, Italy, where he spent two months working as many as 20 hours a day on the first phase of an ambitious effort to create virtual replicas of Michelangelo’s sculptures.

“It was much harder than we expected, but we’ve got data that will knock your socks off,” says Curless, an assistant professor in the UW Department of Computer Science and Engineering. “We are able to get quarter-millimeter resolution, which is good enough to see Michelangelo’s chisel marks clearly. It’s an unbelievably faithful representation of the original.”

The Digital Michelangelo Project, led by Curless’ doctoral research advisor at Stanford University, Marc Levoy, aims to produce the first authoritative computer archive of the Renaissance master’s sculptures.

The high-resolution, three-dimensional images will break new ground in computer graphics research and could help make Michelangelo’s masterpieces available to art lovers and historians around the world.

The wonders of computer graphics technology would allow viewers to examine a sculpture from various perspectives, zoom in on details as small as chisel marks and change lighting conditions to see how they affect a statue’s appearance. Computers might even be used to “virtually” restore damaged sculptures or speculatively complete unfinished works.

Levoy and his team of computer science researchers and students are spending the 1998-99 academic year in Italy. Curless joined the group from mid-January to mid-March to help oversee the initial scanning work on Michelangelo’s “St. Matthew,” “The Unfinished Slaves” and “The David” – all housed in Florence’s Gallerie dell’Accademia

The Digital Michelangelo Project builds on Curless’ doctoral research on an advanced scanning and modeling technique that produced the world’s first 3-D fax. He scanned a small Buddha statuette, created a high-resolution 3-D model of it, and transmitted the model electronically to a stereolithography plant that used the data to produce an identically shaped replica of the original.

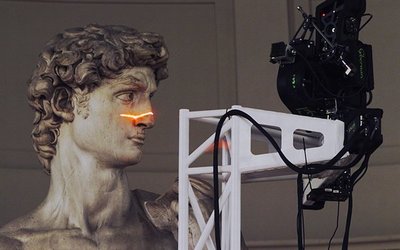

The technique uses laser scanners to shine light on an object and measure the reflection in order to produce a detailed map of the object’s surface. Multiple scans are taken to ensure data is acquired from as much of the surface as possible. Each scan is initially positioned by hand in relation to previous scans, then specialized software automatically aligns and merges all the scans together into a single, complete 3-D model.

The merging process also greatly reduces the amount of space and time required to store and render the model by fusing overlapping scans of a particular surface area into a single representation. This is a big deal, Curless points out, when you consider that capturing all 23 feet of “The David” statue and pedestal required 500 scans and produced a billion data points – enough data to fill tens of thousands of floppy disks.

Even with all of those scans, data is still missing from hard-to-reach places such as between the sculpture’s fingers and between locks of hair. These gaps represent less than 1 percent of the statue’s total surface area and may be filled in later with artistic software. The computer scientists are seeking ways to make clear what is based on real data and what is artistic representation, Curless says, so art researchers will be able to study the models as surrogates for the real sculptures. Another open question is how best to store and display these virtual sculptures, which represent some of the largest computer models ever created and would overwhelm most existing PCs.

“We’ve pushed the state of the art in computer graphics by scanning and modeling some very large objects at very high resolution,” Curless says. “The next step will be to figure out how to display these models, and that will push the state of the art even further. Our dream is to create a virtual gallery where you would open the door, walk up to ‘The David,’ float in the air and look him in the eye. That would be the ultimate experience.”

The $1.5 million project is funded by the Interval Research Corporation and the Allen Foundation for the Arts.

###

For more information, contact Curless at (206) 685-3796 or curless@cs.washington.edu.