April 5, 2007

Every exhibit tells its own unique story to designer Whiteman

When Andrew Whiteman was a child growing up near New York City, he loved to go down to the Museum of Natural History and stand in front of the dioramas in an otherwise darkened hall.

“I’d get lost in that moment,” he says. “It was a cheap vacation.”

No wonder, then, that Whiteman grew up to be an exhibit designer for the Burke Museum — though that isn’t what he started out to be.

He was in a master’s level program in anthropology when he landed an internship at the Arizona State Museum, and no sooner did he get there than he was put in charge of a small project that involved working with a local Native American tribe.

“It was a children’s exhibit and I was to help the curator design the show,” Whiteman says. “In my graduate program I’d been feeling isolated from the reality of my subject matter, but on this project I suddenly felt connected. I was able to meld my intellectual interests with my design side — my head with my hands.”

Whiteman was hooked.

He finished his master’s degree and immediately began working at the Arizona State Museum on an exhibit called Paths of Life. It involved 10 Native American communities living in Arizona and Northwest New Mexico — all “living, breathing, thriving peoples,” Whiteman says. And after that he stayed on in Arizona as a freelance exhibit designer, until the Burke job beckoned.

“I was really attracted to the Northwest,” Whiteman says of his move to the UW in 2000. “And the Burke really is unique. We work with so many cultures here. It’s like walking into the pages of the National Geographic.”

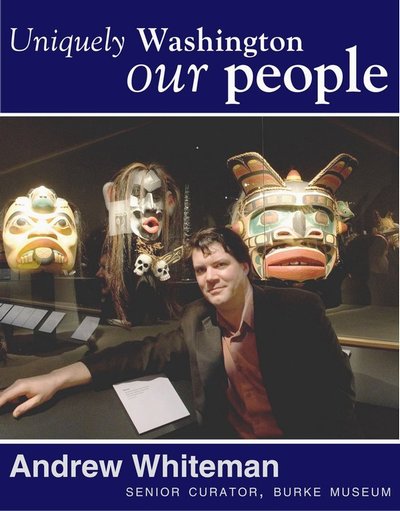

Whiteman’s most recent job was designing In the Spirit of the Ancestors, the Burke’s current exhibition of contemporary Northwest Coast Native art. Designing an exhibit, he says, begins months before the objects appear in the gallery, when he’s invited to meet with the curators who are putting the show together.

“I do a lot of listening,” he says of that time. “I hear them describe the objects and talk about the intent or mood of the exhibition. I find out exactly where it will be located and I try to learn whether we have assets such as video or sound that can be included.”

As those elements firm up, Whiteman begins to take a close look at the objects to be exhibited. Curators make some of the decisions about which objects will be grouped together when they decide on themes for an exhibit, but it’s up to Whiteman to make sure each object looks its best.

For In the Spirit of the Ancestors, the curators decided that all the objects would be grouped according to type — prints with prints, textiles with textiles, etc. And they decided to display an unusually large number of objects.

“When the curators started talking to me about a 2,000 square foot exhibit that involved 75 to 100 objects, I thought, ‘I can’t put all those inside our typical suite of exhibit cases,'” Whiteman said.

“I needed to build something exceptional. So instead of a lot of little cases I have two big ones. In the main gallery I have one very large case that accommodates eight textiles, and then all the rest of the stuff is in the other case. If we had lots of small cases we’d never be able to handle the visitor traffic and still show off all the objects.”

He also paid a lot of attention to lighting. Harking back to his childhood days in the Museum of Natural History, he says he wanted visitors to “get lost in their experience with these objects,” and lighting was one way to do that.

In the end, Whiteman says, it’s all about stories. “Learning stories, telling stories, that’s what I’m doing,” he says. “Every project is different, and it’s fun.”