April 13, 2006

Electrical Engineering celebrates its centennial year

When the Department of Electrical Engineering first came into existence at the UW, electricity remained a luxury in many areas of the country.

The year was 1905, and swaths of the United States were still off the grid. It was before the invention of the vacuum cleaner, electric washing machine, refrigerator or long-distance telephone call. Marconi made the first transmission across the Atlantic just four years earlier, and it would be another year before voice and music would be transmitted via radio.

Today, the department does leading work in areas ranging from genome science and nanotechnology to biorobotics and transportation systems.

“It’s come a long way from the original emphasis on electric machines, electrical transmission and communication,” said David Allstot, chair of the department. “Electrical engineering still includes that, but it’s also at the forefront of all the sciences. The field has become highly interdisciplinary.”

This month, the department will celebrate 100 years of growth and transformation with “A Century of Innovators,” a centennial celebration scheduled for April 29 to coincide with the annual Engineering Open House and UW’s Washington Weekend. The event will include tours of labs, panel discussions, interaction with past faculty members and opportunities to chat with current faculty and students about their research projects. The keynote speaker is Bernie Meyerson, chief technology officer for IBM’s Systems and Technology Group, who will speak on new approaches to computing.

For more information or to register by the April 17 deadline, go to www.ee.washington.edu/centennial or call 206-543-0540.

EE at the UW had its beginnings in the late 1800s, when university leaders, along with the rest of the academic community, began to recognize the need for specialists to deal with the practical applications being developed from the physics of electricity and magnetism. Inventions such as the telegraph, telephone and light bulb and the industries they spawned underlined the growing need for electrical engineers.

Originally, the classes were taught by physicists, according to Rich Christie, associate professor in the department who has put together a history of electrical engineering at the UW for the centennial. Electrical engineering’s location was with the Department of Physics in the basement of Denny Hall.

“The first class in electrical engineering was probably taught by Thomas Eaton Doubt, who was appointed instructor of physics at the University in 1897,” Christie said.

The following year, Doubt was promoted to professor of physics and electrical engineering, and EE, along with other specialized disciplines, was made a four-year degree, although it was still part of the physics department. The UW awarded its first degree in electrical engineering in 1902, with the graduation of Stephen Parker Rowell.

It took the arrival of a new faculty member, Carl Edward Magnusson in 1904, to establish electrical engineering as a stand-alone entity. In 1905, Magnusson, who held bachelor’s and master’s degrees in electrical engineering and a doctorate in physics, was named chair of the UW Department of Electrical Engineering.

“His academic credentials placed him head and shoulders above everyone else around electrical engineering in the informal academic pecking order,” Christie said. “His appointment during the 1905-06 school year marks the birth of the department as a separate, independent academic entity.

Magnusson would hold the position until 1941, guiding the department through nearly four decades of rapid change that saw such innovations as vacuum tubes, AM and FM radio, television and radar.

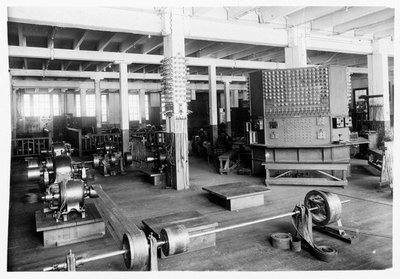

A change of location came in 1910 after the 1909 Alaska-Yukon Exposition, which left the University with several new buildings, including Engineering Hall, located where the current Mechanical Engineering building sits. EE would remain there until 1948, when the Electrical Engineering Building was built just across Stevens Way.

Magnusson became ill in 1940, and died the following year. Faculty member Austin V. Eastman was appointed new chair. Eastman is author of a textbook now considered a classic in the field, Fundamentals of Vacuum Tubes. It is still used nowadays by vacuum tube hobbyists.

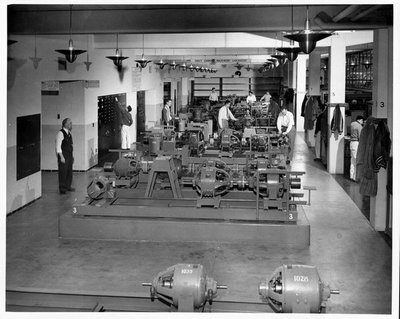

Another of Eastman’s ideas that had a long-term impact on department members came with the construction of the Electrical Engineering Building in 1948.

One of the unique features of the building was Eastman’s brainchild: a Morse code paging system. Each wall-mounted intercom had a telegraph key, which produced a Morse code signal throughout the building when tapped.

Members of the faculty and staff were assigned Morse code letters; the broadcasting of one’s letter over the system was the signal to pick up the phone.

Eastman was inordinately proud of the unusual system, according to Christie. “It expressed both the self-sufficiency of the department, and, to modern eyes, a certain provincial awkwardness.”

Although use of the Morse-code pager faded after the building was expanded with the addition of a fourth floor that lacked telegraph keys, pieces of the system remained visible throughout the building until it was razed in 2002.

Another idiosyncrasy of the structure — one that outlived the building itself — was the set of three bas-relief sculptures embedded in its exterior wall. Carved onsite by Everett DuPen, UW assistant professor of sculpture, the allegorical pieces often mystified the engineers who used the building.

“While consistent with the overall theme of the strengths of the human race found in DuPen’s oeuvre, they are not especially relevant to the field of electrical engineering,” Christie says.

Over the years, puzzlement led to rumors — unfounded — that the artwork was mixed up with some intended for medical buildings on the campus.

The reliefs are currently mounted on the west wall of the Paul G. Allen Center for Computer Science & Engineering, outside the EE administrative offices.

The new building provided expanded space as the department sought to keep pace with the rapid string of innovations over the next several decades: transistors, integrated circuits, the microwave oven, light-emitting diodes, lasers, communications satellites, computing microprocessors, magnetic resonance imaging — all of which overlap into electrical engineering.

A major highlight involved one of the department’s more famous alums. Donald Baker graduated in 1960 with a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering. He stayed on at the UW, working in the lab of Dr. Robert Rushmer, a pediatrician who began researching cardiovascular systems at the UW in 1947. Baker became interested in Doppler ultrasound, working out a technique that allowed technicians to view the inner anatomy of patients with crystal clarity and get precise information about how their bodies were working. He and the research team had prototype instruments running by 1967.

A natural entrepreneur, Baker then set the example for future technology transfer efforts, marketing and commercializing his invention to the benefit of millions.

In 2002, Baker received the Alumnus Summa Laude Dignatus award from the UW, the highest honor the University bestows on an alum.

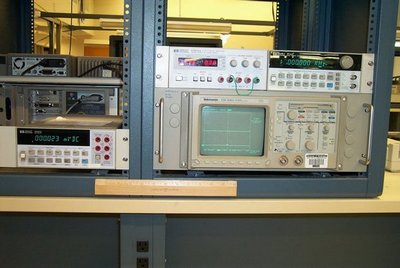

In 1997, a new Electrical Engineering Building was completed, and the department moved into its current home. There, researchers work with colleagues from a wide variety of other departments and fields on projects that run the gamut from genomic analysis and bioengineering to robotic surgery, advanced computing applications and photonics. That, according to leaders in the department, is where the future of UW Electrical Engineering lies.

“The engineer’s role is to build society and solve problems — we create things that make peoples’ lives better, safer and more productive,” Allstot said. “And it doesn’t matter whether you’re talking about something as complex as biomedicine and nanotechnology or as everyday as using your computer or commuting in traffic. Electrical engineering is involved in it all.”