July 8, 2004

Rockin’ on: Climbing them, collecting them are Eng’s passions

The dust jacket of a book Ronald Eng glimpsed many years ago first planted the idea of rock climbing and mountaineering in his mind.

He remembers the book clearly, and now owns a copy. It’s called On Ice and Snow and Rock, by Gaston Rebuffat, the renowned French climber and guide. The colorful cover photograph shows Rebuffat suspended beneath a large overhang of rock, ready to muscle himself up and over the ledge.

“I really liked the drama of the photo, with him hanging there and looking unfazed,” Eng said. The image got him thinking that he, too, might enjoy the thrill of rock climbing. But a long time passed before he started his own climbing career.

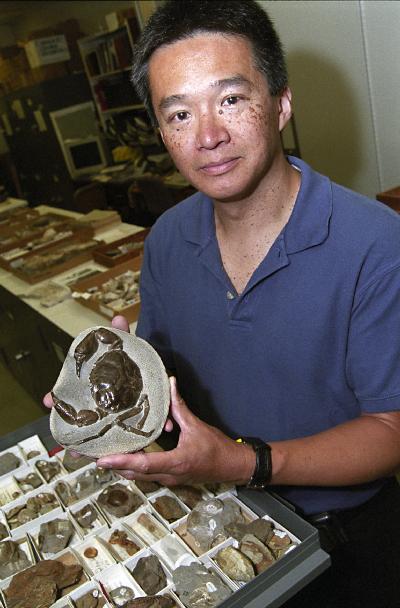

Years later, Eng, now 51, is an avid climber and the newest president of The Mountaineers, a Seattle-based club dedicated to mountaineering and the preservation of wilderness areas. That avocation dovetails nicely with his day job as an invertebrate zoologist and collections manager of the geology division at the UW’s Burke Museum.

Born and raised in the Boston area, Eng earned his bachelor’s degree in biology at Boston University, followed by a master’s degree in invertebrate zoology from Northeastern University. Next, he took a job as a senior assistant at the Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale University in 1979 and stayed until 1982, when he moved to become a curatorial associate at the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University. He said some life changes prompted him to relocate across the country for his job at the Burke in 1991.

Eng said even as a child he was intrigued by climbing and scrambling but didn’t start actively participating until later in life. “I didn’t even take my first hike until my 20s,” he said. An Appalachian Mountain Club rock climbing course back in 1984 piqued his interest and he continued to pursue the interest after moving to the Northwest.

“Our state is like a climber’s dream,” he said. “The terrain in the state offers almost any kind of mountaineering available. We have glaciated peaks, appealing rock climbing and alpine ice.”

Eng said he met his future wife, Laura Martin, when he helped teach a basic climbing course in the 1990s, and she was one of the students.

Several years later, he said, they both happened to be on the same climbing trip to Canada. “We spent a very intense week together, and I started looking at her in a different way,” he said. “The Canadian Rockies in winter — what better spot to get to know someone?”

Martin is now a trauma nurse at Harborview Medical Center. The two became climbing partners after that week in Canada and their friendship deepened. They married in 2001. Another life change came their way on April 15, 2003, when their son Alexander was born.

Of his job as geology collections manager, Eng said, “I am explicitly charged with the day-to-day operations of the collection. The collections manager maintains a sense of permanent order to the collections — to make sure they are accessible to people now and in the future, like an archive.” He said the division has about 3 million fossil specimens in all, some of which date back as far as 600 million years. The specimens fill drawers, shelves and entire rooms at the smallish museum on campus.

MaryAnn Barron, director of external communications at the Burke and a colleague of Eng’s, said his job seems “the perfect combination for him because it mixes his two passions in life — rock and the study of rock, and the climbing of rocks.” Barron said Eng has a real “passion for the Earth,” and is generous with his time and expertise.

One example of this, Barron said, is unrelated to his scientific work. Staff at the Burke were shocked and saddened at the death this spring of Wes Wehr, affiliate curator and well-known artist, author and composer. She said Eng organized Wehr’s memorial at the museum, bringing people in from states away to share their memories. “He put together a beautiful memorial, and he was the backbone of it,” Barron said.

Eng said as a climber he prefers scaling frozen waterfalls, which the Canadian Rockies provide in abundance. The best climbing ice, he said, is on vertical faces, where the water has frozen along its cascading route downward. He said he likes the intellectual as well as the physical challenges of mountaineering.

“It’s problem-solving, mental and physical,” he said. “You have to calculate and physically execute the solution. That’s where people make the big mistake where they get themselves into something they can’t get out of.”

Has Eng himself ever feared death on a climb? Not exactly, he said, thinking back. “It was not so much that I feared death as thinking, ‘I wish I weren’t in this particular spot.’”

Eng said he reminds beginners of the sport’s dangers when he teaches climbing, underscoring the constant need for caution. “I always say, ‘Remember, you can get badly injured doing this.’” He said this sense of informed consent helps people consider whether they have the right skills for any climb they might consider. Some overestimate their skill, he said, but others underestimate it.

He loves his job, but said if he had it all to do over again, as the cliché goes, “My dream job would be to study glaciers. It’s a perfect excuse to spend summers in the mountains,” he said.

And speaking of mountains, there are many peaks that Eng would like to conquer. “There are lots that I’d love to climb, but if I never make it, I won’t be shattered.”

Fatherhood has, pleasantly, taken priority over recreation these days.

But Eng said he may someday take his son along to teach him about the world of mountaineering. Nothing dangerous, of course, just for recreation.

“I look forward to climbing with him,” he said. “I can’t wait for him to be strong enough to carry the pack.”