February 6, 2003

Staffer feeds childhood fossil obsession at the Burke

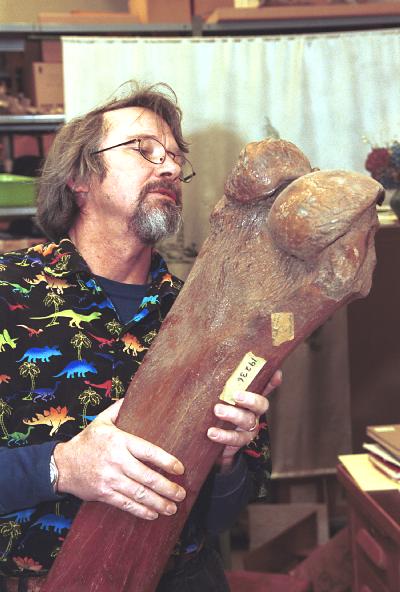

Bruce Crowley is a man who loves his job. It is, he says, the job he always wanted, from childhood on. That might not be surprising if his was a common profession — a doctor, say, or a teacher. But Crowley is a fossil preparator. He’s the guy who chips away the rock to reveal the dinosaur bone or the fish skeleton or the seashell.

Day after day Crowley labors in the basement of the Burke Museum. His domain is a large room filled with a variety of machinery and tools and covered with the fine powder produced when rocks are destroyed in the name of science. His is often slow work, he says. It took him three years to prepare one whale skeleton, for example. But that doesn’t dampen his enthusiasm.

“I like playing with the fossils. I just like having my hands on the fossils. I love the fossils. And it’s like Christmas getting them out of the rocks,” he says.

So how do you get to be a fossil preparator? It’s not exactly on the tip of the average high school counselor’s tongue. Crowley says it began when he was a kid and was friends with the children of sculptor Richard Beyer, creator of the beloved Waiting for the Interurban. When Beyer took his children to the Olympic peninsula to go fossil hunting, Crowley tagged along.

He was instantly obsessed and decided paleontology was the career for him. Trouble is, there aren’t many such positions available and Crowley, a Seattle native, was determined to work right here, at the Burke. Thinking his ambition was nothing but a pipe dream, he embarked instead on a life of wandering. He spent his 20s hitchhiking, and occasionally riding the rails, across this country and Europe, picking up jobs here and there to pay his way.

Fortunately, when he was ready to settle down, Crowley picked a woman with her feet on the ground and her head in the stars. “She had a stable career, and she pretty much insisted I follow my dream,” he says.

So Crowley enrolled in the UW and picked up his long-delayed degree in geology. Then he “forced” his way into the Burke’s basement, volunteering and learning from former preparator Beverly Witte, who continued to work part time despite being retired. Witte’s job had never been filled because of budget problems, but the Burke noticed Crowley’s skill and lobbied the Legislature to fund the position again. After years of volunteering and working on soft money, Crowley finally got the job he’d been waiting for.

That he’s still a fossil-obsessed kid at heart is obvious. Crowley smiles most of the time when talking about his work and laughs frequently. A shelf above his desk holds a collection of miniature plastic dinosaurs. He also has a collection of more than 50 mugs from natural history museums around the country. He complains that outfits with dinosaurs on them often don’t come in adult sizes, so he makes his own Hawaiian-style, mostly dinosaur-print shirts with extra-large pockets for the paperback books he’s always reading.

“I’ll read anything,” he says. “Once I even read a Harlequin romance, just because one of the characters was a paleontologist.”

Visit Crowley and he’s happy to show off the tools of his trade. At various times he uses sand blasters and jackhammers. The sandblasters are large, transparent boxes with holes for him to stick his arms in to do the work under a strong light source. The jackhammers aren’t what you see construction workers using; they’re less than a foot long and light enough to hold in one hand. He also uses acid baths and occasionally, rock saws. For fine work he uses picks like the ones your dentist uses on your teeth.

Everything is in service to one goal — to take fossils that often arrive in fragments or nearly unrecognizable within a rock and make them accessible — either for scientists to work with or the public to see or both. Crowley likes the fact that each specimen presents a different challenge and it’s up to him to figure out what to do.

Take the triceratops skull that was destined for display, for example. A number of the bones were missing, so Crowley created a triceratops head out of Styrofoam. He then cut away pieces of the Styrofoam to make room for the bones he did have. The bones were fastened to the Styrofoam and the whole piece painted an appropriate color.

“It helps to be the kind of person who can repair a blender with a rubber band and some duct tape,” Crowley says of the job. “If you can look at something and figure out how it works when you don’t have a blueprint or a proper set of tools — that’s the kind of technical problem solving capacity we’re talking about.”

Nevertheless, despite his years of experience, Crowley says he never knows when starting a job what he’ll end up with. One time he painstakingly exposed fragments of bone in a rock, only to find a crushed, deformed and partial skull in the end. But another time he was chasing the bone in a rock not thinking it was going to be anything spectacular and wound up with a whole dolphin skull. That, he says, is what makes the job exciting.

Identified as he is with dinosaurs, it’s ironic that Crowley more often works with fossils of aquatic life. We’re not in dinosaur country, he explains — more an area that was once underwater. He’s worked on a number of whale skeletons, and more salmon, snails and clams than he can count.

Though it’s not part of his job description, Crowley still goes out in the field on his own time, but he says that for every week in the field there could be years spent preparing the fossils gathered. And he likes his behind-the-scenes role.

“I think I’m accomplishing a public good and that’s nice,” he says. “But what I really like is when fossils are brought in looking yucky and seeming to be unmanageable, then look good after I’ve been fooling with them for a while. That’s really satisfying.”