February 28, 2002

An India state of mind: Memories of Chandigarh motivated prof’s new book

Vikram Prakash knew what he was doing when he finally sat down to write the story of Chandigarh. “I had to convert the mythical story into the real story,” he says.

It’s a story he’s been living with since childhood, when, he says, “My sisters and I would sit in the smoke-filled drawing rooms while scotch and soda flowed and accusations and denunciations were hurled across the room.”

The discussions were not about politics — at least, not directly. They were about architecture — the architecture of Prakash’s home city, and the larger-than-life man who created it.

Prakash, now an associate dean in the College of Architecture and Urban Planning, grew up in Chandigarh, India, a city created out of whole cloth in the 1950s, just before he was born. The Indian state of Punjab lost its capital to Pakistan when partitioning of the two countries occurred in 1947, Prakash explains, and India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, decided to create a new capital city.

“They thought for a while about picking an old city,” Prakash says. “But then they decided for the symbolic value of saying, ‘We are doing something new and making something great,’ that they would make a new city.”

Chandigarh was the result — built on what had been rural land dotted with 17 villages. To design its major buildings Nehru brought in Swiss/French architect Le Corbusier (he only used one name), the “icon of European architectural modernism.”

Because Prakash’s father was one of the junior architects on the project, Prakash was hearing stories about it from the time he was very young. Though the city was completed by then, people were still arguing about it. Was it a success or was it not? Was Le Corbusier a genius or was he an idiot?

“Nehru once said, ‘The most important thing about Chandigarh is not whether you like it or not but that it hits you on your head and makes you think,'” Prakash says. “Nehru believed that it catalyzed Indian architecture and planning into thinking for itself what should be done instead of sticking with the slow bureaucratic processes it was used to.”

The city certainly made Prakash think. He has been thinking about it, he says, all his life. He first wrote about it in his master’s thesis 10 years ago, then went on to other things. “Then I finally came back and said, ‘Let’s get it out of me.’ I felt like the only way I could get the city, Le Corbusier, that whole legacy out of me was to put it down on paper.”

This spring, his book, Chandigarh’s Le Corbusier, will be published by UW Press.

In a way, the title is ironic. One could just as easily say “Le Corbusier’s Chandigarh,” and it would point to one of the reason’s Prakash was driven to write the book. He tells the story of being given a 10-pound Swiss franc note by a colleague and discovering a picture of Le Corbusier on it. Looking more closely, he saw that in the background was the architect’s drawing for the Chandigarh Secretariat.

“The Secretariat is a symbol of state,” Prakash says. “It’s like the White House. Now, the White House is neo-Palladian English architecture, but can I put the White House on the English pound? So the Swiss claim this building because it was designed by Le Corbusier, who was born in Switzerland though he later became a French citizen. But I have always looked at these buildings as ‘my’ buildings. So the question is, who owns architecture?”

And whose vision is embodied in the architecture? Prakash argues that the Indian bureaucracy involved in the project made the decision to turn Chandigarh into a modern garden city reminiscent of the districts occupied by the English in Indian cities before independence — a sort of colonial appropriation of the master’s lifestyle. Le Corbusier — who designed the government buildings — had a different idea.

“Le Corbusier dedicated the whole capitol complex not to the city of which it was the head but to his own romanticized vision of India embodied in a happenstance village which exists just north of the capitol,” Prakash says. “I think he subconsciously identified the village people and the thousands of manual workers on the site as a romantic conception of the noble savage. And he had this kind of strange, almost sad vision that somehow he was designing for them.”

Prakash bases this view on several parts of Le Corbusier’s design. The architect built artificial hills between the capitol buildings and the city, and the typical government employee enters the complex through an underground roadway. On the ground level, an esplanade with reflecting pools actually faces the village, and is used mostly by the village people. Children play cricket there, Prakash says, and villagers hang laundry there and bathe their water buffaloes in the reflecting pools.

In his sketchbook, Le Corbusier wrote, “The view of the existing village is intact and beautiful.” But today, the architects that Prakash takes to visit Chandigarh complain they can’t get a clear photo of the capitol that isn’t marred by a clothesline filled with laundry or a villager on a bicycle.

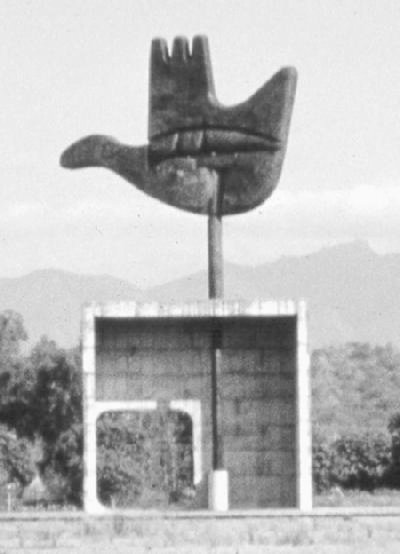

Perhaps the ultimate in conflicting visions is represented by the Open Hand, a Chandigarh monument that has become a symbol of the city. Le Corbusier designed it in the 1950s and begged Nehru to have it built, Prakash says, but both men were long dead by the time it actually was built — in the 1980s. The reason was political. Le Corbusier tried to persuade Nehru to build it by telling him it was a symbol of India’s non-alignment in the Cold War. But Nehru thought it had become a symbol of the modernism he had pushed too hard and which was then becoming unpopular. So he was afraid to have it built.

Much later, when the idea of the monument was revived, its symbolism was changed. One tourist brochure calls it “a giant metallic hand of an unseen power” — which Prakash says is a Hindu concept. Another says it represents Indian civilization’s “greedlessness and magnanimity.”

“It really means whatever anybody wants it to mean,” Prakash says.

But the final irony is that while the Open Hand is a symbol of Chandigarh — stamped on every official document — it is also the symbol of the Fondation Le Corbusier, the archive of the architect’s work.

Who owns architecture? Prakash wrote his “final answer” in his book:

“Trademarks can be copyrighted, but the public inhabitation of architecture opens it up for appropriation by all those who want to make a claim. It is a symbolic text, simultaneously woven into as many life-worlds as would have it. Things mesh, inevitably. In the end, therefore, I felt vindicated by the intentions of the Swiss government: if they could claim the Chandigarh Capitol as their own, surely I could claim Le Corbusier for India.”

Now that the book is finished, Prakash says he feels finished with Le Corbusier. But there is a final hurdle to surmount. Prakash’s father — who went on to become the dean of Chandigarh’s architecture school — has written two books about the city but hasn’t seen his son’s version.

“He’s seen some earlier drafts,” Prakash says. “I’m a little nervous about showing him the finished book.”