March 16, 2000

Winds in Pacific climate cycle can foretell Gulf of Mexico hurricanes

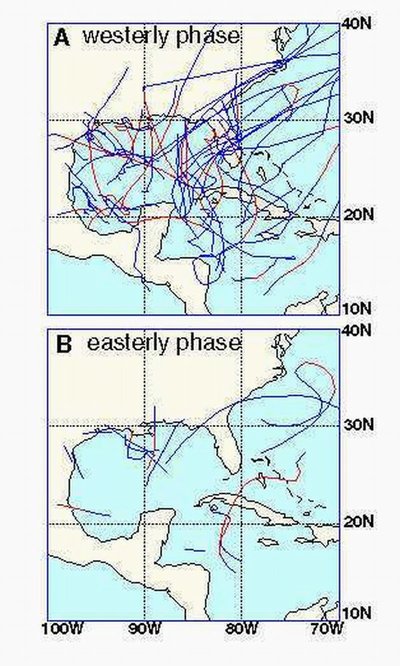

A short-term climate cycle that builds in the Indian Ocean and moves eastward through the equatorial Pacific Ocean is a key factor in the formation of hurricanes and tropical storms over the Gulf of Mexico and the western Caribbean Sea, University of Washington researchers have found.

The findings relate to westerly winds in the Pacific associated with a cycle called the Madden-Julian Oscillation. Data culled from climate and weather records from 1949 through 1997 show that, about 15 days after detection of those winds in the western Pacific, hurricanes and tropical storms are four times more likely to form in the gulf and in the western Caribbean, the scientists said. The area extends from eastern Texas to about the eastern edge of Cuba.

“If you saw a relatively strong wind burst coming across the western Pacific, you could say that within a couple of weeks you might expect hurricane activity in the Gulf of Mexico,” said Eric Maloney, a UW atmospheric sciences doctoral student. He and Dennis Hartmann, a UW atmospheric sciences professor, report their findings in the March 17 edition of Science.

Having advance knowledge that conditions will be favorable for hurricanes to form will give officials and residents of the Gulf Coast and Caribbean islands more time to prepare, and also could prove valuable to shipping interests, the scientists said.

“You can say maybe a week in advance that there are likely to be hurricanes in the Gulf of Mexico, but I can’t tell you whether they’re likely to hit New Orleans or Galveston,” Hartmann said.

Florida appears to be very vulnerable to such storms, Maloney said. “Florida is much more likely to be hit by a hurricane or tropical storm during westerly events.”

The Madden-Julian Oscillation repeats every 30 to 60 days. It rises in the Indian Ocean and stays close to the equator as it moves across the Pacific. The leading area of the system typically carries the easterly winds that are predominant in the tropics. The center of the system often contains storm activity, and the westernmost section carries the telltale westerly winds.

Maloney and Hartmann examined wind speeds at an altitude of about 4,500 feet. They found that when easterlies averaging 7 or 8 miles per hour were replaced by westerlies of the same strength, the difference of 15 mph or more correlated strongly with increased hurricane formation in the gulf and the western Caribbean. In addition, there are indications that the storms generated are more powerful if the westerlies in the Pacific are stronger.

The researchers examined data for June through November, considered the Atlantic Ocean hurricane season, in each of the 48 years included in the study. They found that conditions in the Madden-Julian Oscillation were strong enough to influence hurricanes about one-third of the time. Information from earlier years is sketchier and typically comes from shipping reports. In later years, most of the data were collected by satellite.

“We originally did the analysis from 1979 to 1997 and the results are exactly the same as for the earlier period,” Maloney said.

Previously, Maloney found a link between the stronger westerlies and the formation of hurricanes over the eastern Pacific, but there was no indication then that what was happening over the Pacific related to storm formation in the Gulf of Mexico and western Atlantic Ocean.

“The topography of Mexico is high, which is why at first we just looked at the Eastern Pacific,” Hartmann said. “It was only later that Eric looked at the Gulf of Mexico and found the signal was just as strong, which was a surprise.”

The research was paid for by a grant from the National Science Foundation.

The two plan further research into how the topography of Mexico and Central America interacts with the weather systems, and to better understand the relationship between the Madden-Julian Oscillation and hurricanes near the Americas. They also plan to look for similar links to storms forming in the central Atlantic.

###

For more information, contact Maloney at (206) 685-9303 or maloney@atmos.washington.edu, or Hartmann at (206) 543-7460 or dennis@atmos.washington.edu