November 30, 2006

Dance fever: Recovery can be hard

If there were a 12-step group she could turn to, one member of the UW dance faculty might find herself saying, “Hi, I’m Juliet McMains and I’m a glamour addict.”

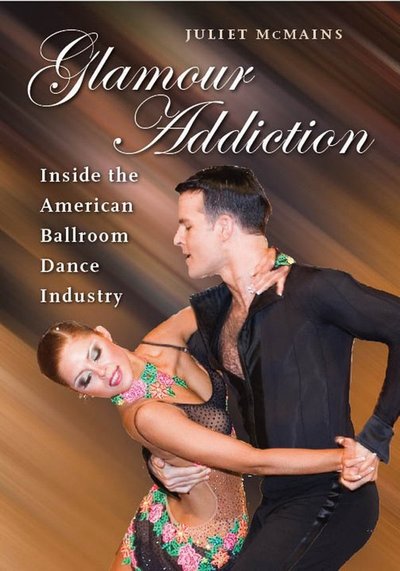

Instead, McMains is teaching World Dance History and Beginning Salsa at the University and staying carefully away from the professional ballroom dance world that once held her in its grip. And she’s turned her scholarly eye on that world in a recently published book called Glamour Addiction: Inside the American Ballroom Dance Industry.

Thanks to Dancing with the Stars, most of us know a little about what looks like the terribly glamorous world of ballroom dancing. But McMains is an insider with the unusual history of having looked critically at the world of competitive ballroom dancing, called DanceSport, even as she pursued success within it. Most DanceSport professionals, she explains in the book, come from working class backgrounds or are recent immigrants and have little more than high school educations. She, on the other hand, became deeply involved in the dancing while attending Harvard University, and continued pursuing it while working on a doctorate at the University of California Riverside.

Throughout those years, she was wracked by conflicting feelings. “I was really disturbed by how much the dance form that I loved seemed to embody so many of the values that I despised,” she said. “At the same time I was completely obsessed with it.”

Her addiction started innocently, when she saw a ballroom dance performance as a teenager. Already trained in ballet, tap and jazz dance, she took one look and knew that was something she had to do. In her book she writes,

“There must have been a man in the partnership, but I only remember the woman. She was unbearably sexy and sophisticated, and I made up my mind right then and there to become the heroine I imagined her to be.”

McMains began taking group lessons, which soon turned into private lessons, and during her undergraduate college years, she began entering ballroom dance competitions for amateurs, winning a case full of blue ribbons. Then she turned professional, moving ever higher in the DanceSport standings while simultaneously going to graduate school. She was twice a national Rising Star professional finalist, but none of it brought the satisfaction she was looking for. She became, in her own estimation, a victim of what she calls in the book the Glamour Machine.

“I wrote this book for the person that I was when I started ballroom dancing,” she said, “because I wish there had been a book I could have turned to so I could have said, ‘Oh, that’s why I’m feeling these conflicting feelings.’ Whether I would have made the same decisions if I had had this book when I started, I have no idea, but at least I would have been informed.”

The ballroom dance industry’s Glamour Machine, McMains argues in her book, is built around a promise of personal transformation — a promise that glamour will give a person whatever he or she wants. For a person without friends, glamour promises friends, for a person who feels too old, glamour promises youth, for a person with no romance, glamour promises romance.

“It will continually shift to promise whatever you’re missing,” McMains said. “But it never delivers. It just keeps you wrapped in this cycle of perpetual longing.”

The same could be said of any number of products on the marketplace that promise to answer the consumer’s prayers, but McMains argues that dance is particularly powerful because there is so much physical touch involved. A person who signs up for dance lessons will be paired one on one with an accomplished dancer whose job it is to give the student total attention, and in the steps of the dance, a simulated courtship takes place.

That part of the Glamour Machine also leads to some of the abuses of the industry. DanceSport teachers, especially female teachers, are often sexually harassed by their students, McMains said. The false intimacy set up by the dancing leads the student to expect more, and sometimes to press those claims forcefully. The teacher, who stands to make the most money from regular students, feels coerced.

The situation is heightened when DanceSport competitions are added to the mix. There, students who compete in the pro-am division do so with a teacher as their partner. The students pay all expenses for both themselves and the partner to attend the competitions, which go on for several days and take place at nice hotels.

The competitions typify the expense of DanceSport. Students at studios are pressured to sign up for ever more expensive training packages, then to enter competitions. For professionals, the cost is even greater. They often spend $30,000 a year on coaching, costumes and travel, McMains said. She said many professionals hope to move up in social class through the dancing, but the purses in the competitions are small — typically only $1,000 for first place — so dancing is hardly an avenue for acquiring wealth. In fact, DanceSport teachers are little more than indentured servants for the studios they work for, with the only avenue up being to open their own studio.

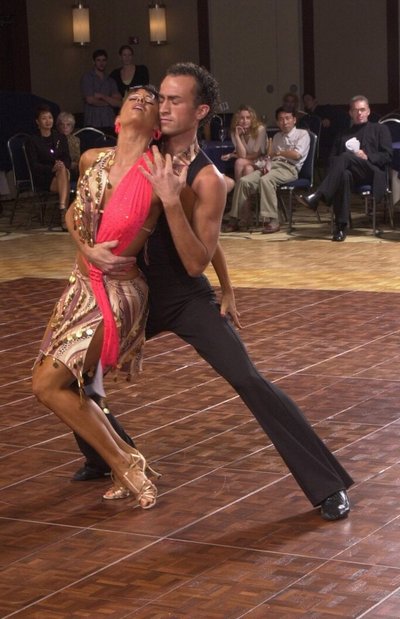

McMains also sees a form of racism in the DanceSport industry. One dance classification in the competitions is called Latin, yet the dances labeled as Latin bear little resemblance to the dances as practiced in their countries of origin. Moreover, the dancers — who are overwhelmingly white — perform the dances in dark body paint. McMains calls the practice “brownface,” comparing it to the blackface in minstrel shows.

With all its problems, however, McMains insisted she wouldn’t discourage people from getting involved in ballroom dance. “There are great benefits to the dancing,” she said. “Any dance helps people improve their command of their body and increases their self confidence. It’s also great exercise and good for stress relief. You just have to understand the dangers going in.”

She understands those dangers all too well. Her last professional competition was in 2003, and she hasn’t been to one since. “If you’re a glamour addict,” she said, “you’re always recovering.”