February 16, 2000

Ecosystem health depends on complex relationship between organisms

It has long been known that a diversity of plants and animals can be a good indicator of a healthy ecosystem. But University of Washington research, to be published in the Feb. 17 edition of the journal Nature, suggests the health of the ecosystem is rooted in a complex codependency between plants and animals that produce organic matter and simple organisms that break it down.

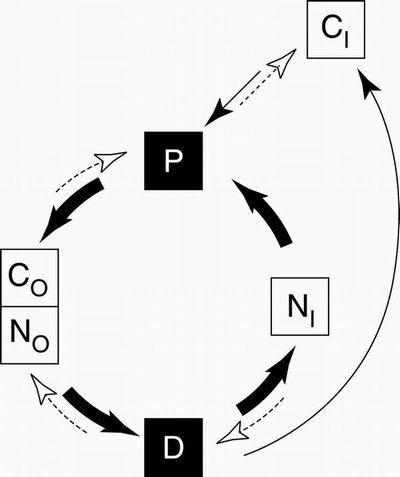

Plants and algae – referred to as producers – acquire nutrients from inorganic sources supplied by fungi and bacteria – called decomposers. Decomposers in turn acquire the carbon they need from the producers. The number of species in each group appears to correlate with how well the ecosystem functions, with greater diversity bringing more efficiency, said Shahid Naeem, a UW assistant zoology professor and lead author of the study described in Nature.

“The effects of producer diversity on ecosystem function is only part of the picture,” he said. “Decomposer diversity is also important. You can’t separate them.”

The research, conducted by Naeem and UW graduate students Daniel Hahn and Gregor Schuurman, provides insights into what occurs when a complex ecosystem is turned into a simpler one, clearing rain forest to make way for a banana plantation, for instance, or converting a prairie to a wheat field.

The findings came from the yearlong study of 112 microcosms created in petri dishes, each containing 50 milliliters of a growth medium and kept in the same temperature and light conditions. Each petri dish was loaded with zero, one, two, four, eight or 12 species of bacteria and zero, one, two, four or eight species of algae. (The only combination not used was zero bacteria and zero algae.)

The researchers found that algae production varied greatly, depending on the number of bacteria species introduced, and correlated directly to the diversity of both algae and bacteria species. They also discovered that increasing the number of algal or bacterial species could influence the number of carbon sources consumed by bacteria.

The research, conducted in 1998 and paid for by a grant from the National Science Foundation, suggests that the relationship between producers and decomposers strongly influences the way an ecosystem responds to changes in biodiversity, Naeem said. That means activities that might seem benign to an ecosystem, since they don’t appear to affect plants and animals, actually might alter the ecosystem by affecting decomposer species diversity. That in turn would affect producer species, the research indicates.

Most human activities that lead to a loss of biodiversity, such as habitat disturbance or modification, affect both producers and decomposers. The codependency between them, Naeem said, is an important consideration for conservationists dealing with an extinction rate that some researchers believe could cost the world half its species by 2050.

Some scientists, he noted, argue that humans alone affect species extinction in a way similar to an asteroid impact such as the one 65 million years ago to which the extinction of the dinosaurs has been attributed.

“It’s all disappearing very, very quickly. This doesn’t necessarily mean they’re all disappearing from the face of the Earth, but as you walk you will encounter fewer species per hectare, or per acre, or per meter,” he said.

“We’re a single species, but we’re a powerful species.”

###

For more information, contact Naeem at (206) 616-2122 or naeems@u.washington.edu