December 7, 2006

New online museum makes Olympic Peninsula history more accessible

The UW Libraries have partnered with communities on the Olympic Peninsula to create an unusual online museum that provides access to much historical material that previously was in private hands.

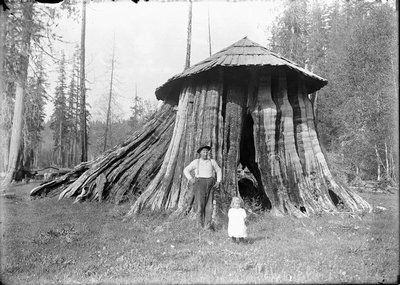

The Olympic Community Museum, www.communitymuseum.org, which was launched recently, encompasses material relating to the history and people from the “West End,” including photographs, diaries, letters, images of artifacts, maps and other written documents.

The idea of an online museum had been raised at community meetings in Forks, but it began to take on reality three years ago when Rod Fleck, a UW alum and city planner in that community, contacted the UW’s Educational Partnerships and Learning Technologies office. Partnership office staff in turn approached the Libraries, according to Paul Constantine, associate dean of UW Libraries in charge of research and instructional services.

“Vi Riebe, a member of the Hoh tribe, began by asking if we could make certain pictures and stories that she had in her family available on the Web,” Fleck said. “We expanded the discussion, thinking about how we could put any historical object on the Web, and what a virtual museum might look like.”

“EPLT and Libraries staff wrote a grant to the Institute for Museum and Library Services, a federal agency that likes partnerships,” Constantine said, “and obtained funding for a three-year project to assemble the information.”

Some of the information was available from public sources in Forks, Port Angeles, La Push and even in UW Special Collections. “But much of the material was in people’s attics and drawers,” Constantine said. “So we tried to get the community involved.”

Because the libraries was seeking material from individuals and groups that in many cases had never worked with museums or the UW before, the UW team worked through local individuals who organized community meetings and acted as trusted intermediaries. The community meetings also were venues for discussions concerning the background behind photos and documents about which historical information was scant.

Because the Olympic Peninsula was one of the last developed areas in the lower 48 states, the historical record does not extend very far back — which was not necessarily a bad thing, since those attending the meetings could recall some of the events and activities recorded in documents and photographs from their own experience or from stories told to them by their parents.

The team also broke new legal ground in licensing material from tribes and individuals for public access. “Preston, Gates and Ellis created model documents, on a pro bono basis, for securing permission,” says Anne Graham, UW senior computing specialist at the libraries. “For tribes, the concept of copyright doesn’t necessarily coincide with US law, so Preston, Gates was performing groundbreaking work in this area.”

When the Web site was unveiled in October in Forks, the community was thrilled, Constantine says.

“Now, they feel more connected to the world,” Graham says. “And their sense of pride in their community has been enhanced.”

Some local leaders see the online museum as part of a project to enhance tourism. A walking tour of historic Forks now includes large, vintage photographs of the buildings in their heyday. The photos, taken from the online museum, were enlarged and mounted by staff with the UW’s Olympic Natural Resources Center in Forks.

Users can browse the museum Web site in a number of ways. All 12,000 items on the site are searchable, but the site also contains nine special exhibits, ranging from information about the great Forks Fire of 1951, told in oral histories, to a short course in the Makah language. There are also curriculum packets geared toward high-school age students, developed by doctoral students in the UW Department of History and the Center for the Study of the Pacific Northwest.

Constantine describes the community museum as “typical, except that, for most museums, when you go there you can see only a portion of the collection. In this museum, everything is accessible.”

“What did we get?” asked Fleck. “Exactly what we’d hoped for, and more. There is so much material you can just go through it for hours and not realize that time has passed. As a UW alum, I know that one criticism of the University has been that it didn’t often consider issues beyond the campus. But this has gone way beyond the borders of the University. It’s a different type of virtual museum, and the tools that have been developed in this process can be used by those concerned with community history around the world.”

Although the grant-funded portion of development has ended, the UW team is still interested in finding ways of adding material to the site, some of which is continuing to flow in to community representatives on the West End. “We’d like to find a way to make it easier for people to submit information about images in the collection, for example,” Constantine says.

The Web site was designed by Angela Rosette-Tavares. Theo Gerontakas, a metadata librarian, entered most of the information about the items in the collection — and in many cases collected the metadata as well. The community partners included many tribes and organizations on the peninsula. Material also came from the National Museum of the American Indian and from the Museum of History and Industry.