November 16, 2006

The world’s unhappiness is ours, Farmer tells students

Paul Farmer came to the UW on Monday, urging his listeners to regard health care not as a privilege but as a right, something that must be part of the social contract.

“The unhappiness of the world,” he said, “is our unhappiness.”

A Harvard specialist in infectious diseases, Farmer founded Partners in Health, which builds and operates clinics for destitute people in places such as Haiti and Peru. The work has included some of the most difficult health problems, including AIDS and tuberculosis. Farmer and Partners in Health are the subjects of Mountains Beyond Mountains, written by Pulitzer Prize winning author Tracy Kidder. Earlier this year, a University committee chose Kidder’s book the lead read in UW’s new Common Book program.

Farmer, 47, is tall and wiry. He shuttles between the clinics, his faculty job at Harvard University Medical School and his home in Rwanda.

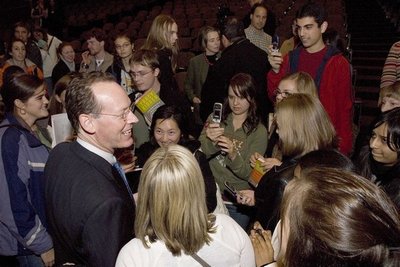

Monday morning, in a question and answer session with about 60 students, most of them in the Honors Program, Farmer said he’s optimistic about American students. Many, he said, realize their degree of privilege and are committed to community service.

The sheer volume of America’s resources makes the decisions of its citizens more critical than those of most other countries, Farmer said. “The trick now,” he explained, “is to think globally and locally.”

Consider, he said, that each year in Malawi, about 1,800 women per 100,000 die in childbirth compared to none in Iceland. Dying from childbirth can and should be stopped, not merely because of individual deaths, said Farmer, but because of the effects on the children who remain.

Peter Kithene, a 24-year-old native of Kenya and fifth-year senior at the UW, founded the Mama Maria Clinic for widows and orphans in Kenya. He asked Farmer what he would have done differently when beginning his clinics in the early ’80s.

Partnerships, said Farmer. He wishes Partners in Health had sooner sought alliances with other groups, including governments, even though they can pose bureaucratic challenges. Wryly referring to his recent efforts to build clinics in Rwanda, Farmer said, “Rwanda has a lot of directors.”

Farmer also said getting the right people in place has been frustrating. He cited an e-mail that day about a child who died because someone didn’t do a job properly. But, he said, persistence is still the key.

Pragmatism counts, too. A female UW student asked what field of work could make the most difference in eradicating poverty. Choose something you love, something you can do for a lot of years, Farmer said. And remember, there’s plenty of service work to be done in places like Seattle.

After the student session, Farmer had lunch with about 20 members of the Haitian community in Seattle. Waid Sainvil, who recently opened Waid’s Haitian Cuisine Bar & Lounge on East Jefferson Street, served Creole chicken and rice. He and his chef, Nurson Desruissau, said they want to send profits from the restaurant back to Haiti for a school, a clinic and a hospital. Around a large table in Parrington Hall, Farmer talked and listened to stories of Haiti, smoothly switching between English, Spanish and Creole French.

Some people in health and public policy still question whether Farmer’s work is widely replicable. They say it’s very expensive and much depends on the charisma of Farmer himself. However, people like Dr. Michael Chung, an acting instructor in the UW Division of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, believe Farmer’s work is replicable — it simply takes determination.

Chung trained with Farmer at Harvard and works in an HIV clinic in Nairobi, Kenya supported by the UW. The clinic uses Farmer models of high-quality Western care that save money with generic medications, lower-cost labor and less frequent lab work. In the last two years, the clinic has treated about 3,000 patients for about $400 annually apiece. (In his talk Monday night, Farmer said comparable treatment in the U.S. costs at least $10,000 per year.)

Setting up the clinic, training workers and running the place have been difficult, but doable, said Chung. “We have shown we can do it.”

Chung is also watching to see what Farmer does next: “He’s constantly pushing the envelope of what’s possible.”

- Watch Farmer’s talk via UWTV at: http://www.washington.edu/externalaffairs/mediarelations/galleries/farmer/.