January 15, 2004

Man captures landscapes big and small

One thing you won’t see a lot of in Bob Underwood’s photography portfolio is people, at least not in any recognizable form.

|

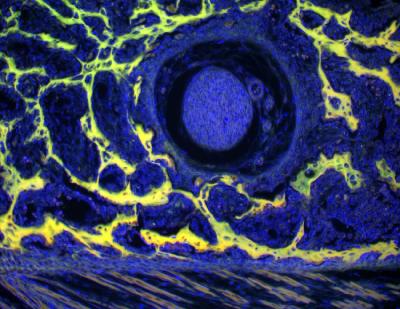

| Underwood says one can see images reminiscent of nature in almost all of his photos, whether they’re from the macro-world or the micro-world. This is an image of human flesh magnified about 5,000 times. |

Underwood is a master of the big and the small, the micro and the macro. The only photos he takes of people are at the cellular level. He captures morphological images for the UW’s Division of Dermatology. And on the other end of the spectrum, he shoots landscapes, images in black and white of wide open spaces, conjuring the works of Ansel Adams.

“I have a perpetual need for balance,” the soft spoken Underwood says to explain his broad photographic repertoire. Indeed, even the technology he uses ranges from antiquated on the one hand to cutting edge on the other.

The images he captures at the UW are helpful for scientists searching for ways to compare diseased or damaged cells with healthy ones. But one can’t look at the images without seeing much more. The vibrant colors and the abstract images are nothing and at the same time could be almost anything.

“I’ve been doing it for 19 years and I like it,” he says. “It doesn’t get tiring. Physically, sometimes, I get tired. But it’s not emotionally tiring. I get sort of philosophical about it. I get to look into a world that other people can’t see.”

That could soon change. Underwood is so taken by the colorful images that he’s decided to publish a children’s book using scenes from the molecular world. The writing has been completed. The next step, he says, is to find someone to publish the book, which has a working title of There’s No One I’d Rather Be Than Me.

|

“Anytime I entertain the idea of making money or trying to find a market for my work, it just screws everything up,” he says.

For example, there was the time he decided to show some of his work in a local gallery. Two pieces sold, but before Underwood collected a paycheck the gallery owner had closed shop and hightailed it out of town.

“I thought that was a message.”

The message was reinforced when on another occasion his work was stolen right off the wall. Still, he thinks it might be of value to share the images with the public, even if there’s no money involved.

“It doesn’t interest me to market my things, but I am toying with the idea of having some shows, just for the sake of showing the work, not to make money.”

The tools he uses are as diverse as the images they help him collect. To capture the minute inner-workings of the human body he uses a powerful microscope that can magnify things up to 100,000 times their original size. The scope works in connection with a high-end computer. To capture the landscapes, on the other hand, Underwood uses antique, large-format cameras, three of which he’s rebuilt himself.

His interest in the cameras goes back to some of his earliest days exploring photography. After enrolling in Everett Community College’s program and visiting area galleries he developed an eye for a specific kind of photograph.

|

“I got really hooked on these images that you could almost walk into. They had so much detail. You could see every leaf and every little vein on every leaf. On a pine tree you could see every needle. I got curious as to how they could do that.”

The answer was to use large-format cameras. He first went up to a 2¼-inch square format, then to 2¼ by 3¼, then to 4 by 5 and finally he rebuilt a camera that shot onto a 5-by-7 inch plate. One of the cameras he uses was built in 1872. But the age of the equipment, he’s found, doesn’t matter. The size of the image plate is the key factor, with larger plates producing more detailed images.

“If you take a 35mm image of a leaf, you might have five levels of gray to describe the topography or texture. But if you do it with a 4-by-5 inch view camera you get these really subtle and smooth gray values. It almost comes to life. And since you’re able to develop each image separately you can completely control the contrast.”

All in all, he says, it’s much more precise and contemplative than the standard process most photographers use today.

And while the technical differences between shooting at work and shooting the landscapes are significant, Underwood sees a great deal of similarity in the final products.

“The overall philosophy I have toward images is to look for metaphors in natural forms. Our eyes try to make up landscapes when looking through the microscope. We know things about our existence and we tend to see natural forms like sunsets and we attach our feelings to that. So part of looking at landscapes, whether they’re in the microscopic world or the macroscopic world, is looking at metaphors that enhance our understanding of our existence.”