April 3, 2003

Staffer works to eliminate water waste

Mark Davis wants your help in eliminating a major waster of water found in many UW laboratories. The culprit is water distillers, a common piece of lab equipment designed to turn de-ionized water into distilled water, using tap water as a coolant. In the process, Davis says, any of the three kinds of water can end up going down the drain in unnecessarily large quantities.

Davis, who works for the Scientific Instruments Division in health sciences, discovered the problem recently while repairing a distiller. He noticed that after the machine had shut down, water continued to flow.

“I got to wondering how much water was being wasted, so I measured it,” Davis said. “It turned out to be 42 liters per hour.”

Concerned, Davis reported the problem to a lab manager, who suggested he talk to Facilities Services. They in turn referred him to the Conservation Project Development Team, a collection of people from across campus who are working to conserve energy. The team empowered Davis to seek out distillers across campus and install water-conserving features when they’re needed.

So Davis is looking for distillers, which he says are found in nearly every laboratory group on campus. He’ll come out, check the distillers for water wastage and repair them when necessary.

He says that ironically, it is the distillers’ very reliability that has led to the problem. “Distillers do break down, but they’re pretty basic and easily repaired, so there are some machines as old as 30 years that are still being used.” And it is these older machines — built at a time when water was plentiful — that are most likely to waste water.

Upgrading the machines is simple. Davis explains it this way: In a typical distiller, de-ionized water comes in and fills a chamber. Heating elements heat the water and steam from it rises into an area containing circular tubing filled with tap water. The tap water cools the steam and it condenses into a reservoir of distilled water.

“The reservoir should have a float in it so that when the water fills the reservoir, a switch will be triggered to turn the machine off,” Davis said. “If the machine doesn’t have the float, the excess distilled water will overflow and go down the drain.”

All but the oldest distillers have the float, Davis says, but many don’t have a valve that will cut off the de-ionized water when the machine shuts off, and others lack a valve to shut off the tap water that is used as a coolant. As a result, it’s possible to have de-ionized and/or tap water still running after a distiller’s reservoir is full and the machine shut down.

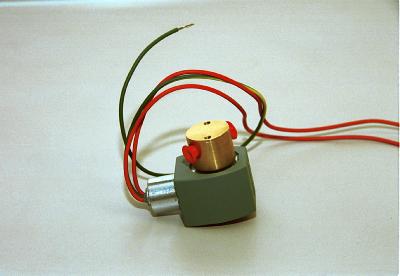

“What I do is install a solenoid valve that automatically shuts off the water sources when the machine is off,” Davis said.

The fix is a relatively simple one, requiring about an hour and a half of his time. That should prove to be a good investment, considering that the University pays $7 for every 100 cubic feet of water it uses.

Anyone with a water distiller is asked to contact Davis via e-mail, mad2@u.washington.edu or voicemail, 206-685-0474. Labs won’t be charged for his services.