November 8, 2001

In Adams novel there’s no place like ‘Home’

Back in the 1960s, after Professor Emeritus Hazard Adams had completed more than 10 years of teaching, he decided it was time to put his money where his mouth was. “I had been teaching literature, and I thought that if you’re going to teach literature you ought to have tried to write,” he says.

Adams had written scholarly articles, of course, but he hadn’t written anything like the material he was teaching. So he started a novel, following the dictum given to beginning writers to “write what you know.” The resulting work, The Horses of Instruction, was set in a university in the ’50s.

“It seemed to me that in that period, the academic profession changed radically,” Adams says. “Faculty became entrepreneurs. Their loyalty was no longer to the institution but to their own careers, or to their disciplines. I tried to write about that.”

Having gotten his feet wet as a novelist, Adams went on to write a second academic novel, Many Pretty Toys, which was set in the late ’60s and revolved around the political issues of the time, primarily Vietnam.

But there’s something about the number three that signals completion. So Adams couldn’t be content until he’d done a trilogy. He’ll be reading from and talking about his third academic novel, Home, at 7 p.m., Monday, Nov. 12 at the University Book Store.

“But that’s it,” Adams says. “I’m not writing any more academic novels. I’m finished with that.”

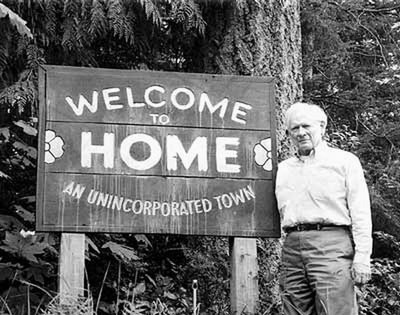

Home is set here in the Northwest, where the protagonist, Edward Williams, is a historian who has become interested in utopian communities, particularly one called Home. Home was a real community located in a sheltered cove that is west and slightly north of Tacoma. Founded in 1894, it was to be a place where anarchists could live with no government, cooperating as much as they chose in order to get things done.

Adams became familiar with Home because he owns property on nearby Hartstene Island, where one of his neighbors was Murray Morgan, the late historian of the Northwest. “Murray and I had a conversation one time about Home, and I got interested in it,” Adams says. “So I went to the UW library and discovered they had some materials on it, including copies of the newspaper that was published there.”

Adams’ research eventually led him to the granddaughter of one of Home’s founders, who lives on the site of the original community. Though the commune collapsed in 1920, there is still a collection of houses there and it is still called Home. At the granddaughter’s house, Adams viewed several scrapbooks full of historical materials about Home. By that time he was hooked; he would have to write the story.

The novel Home places Williams in the middle of two academic controversies while he is researching the historical Home – a sexual harassment case and a battle over the appointment of a professor to a prestigious chair. And though Adams insists the university portrayed is not the UW and that none of the characters are based on people here, he writes knowledgeably about the internal squabbles and jockeying for position among various factions of the faculty and between faculty and administrators.

The knowledge comes from personal experience. Like his protagonist, Adams became a dean and then a vice chancellor (at the University of California Irvine) before electing to return to the faculty back in the ’70s. “The catalyst was when I was first asked if I would be a candidate for president somewhere,” he says. “I looked at myself and thought, ‘I don’t want to do that.’ I got out the next year.”

In the book, each chapter is preceded by an actual article from the Home newspaper, Discontent: Mother of Progress, allowing Adams to draw parallels between the academic infighting and the conflicts between the Home community members and the surrounding populace. But he says the novel is not a satire.

“Novels about academia tend to fall into two groups,” Adams says. “Satires are one group, and the other involves a sort of serious over-identification with the institution. I think you don’t have to be solemn to be serious and you don’t have to be satirical to write intelligently about academic life.”

Whatever academic novels may be however, writing them differs dramatically from the scholarly writing academics generally do. Adams has written 20 scholarly books and only four novels, and he says that academic writing requires much more preparation – mastering an area of study and being aware of what other scholars have contributed to the field.

“In a novel it seems to me you start in a more pristine state. You don’t have all that baggage,” he says. “Even when you do research you can pick and choose which parts of what you find out that you want to use. In some ways it’s more fun.”

Enough fun that Adams is already thinking about his next novel, which will be about dogs. “I think writing is an intellectual adventure,” he says. “There is something compulsive about it. I enjoy writing, and I enjoy it now more than I used to because I don’t have a sense of professional stress about it.”

That’s because Adams has been retired from the Comparative Literature Department since 1995. He has been teaching one quarter per year since then, however, giving him a full 50 years in the profession.

This year he retires for real. To do more writing? Adams smiles. “We’ll see,” he says.