Lesson Six: The Continental Fur Trade

A type of steel trap used by an early fur trapper

in the St. Paul, Oregon, area. (Harvey J. McKay, St. Paul, Oregon, 1830-1890. Portland, Binford and Mort, 1980. p. 2)

Fur Trade Timeline |

Pacific Fur Company, 1811-1813s

North West Company

Hudson’s Bay Company

Oregon Treaty of 1846 defined the boundary between the U.S. and Canada at the 49th parallel, and brought an end to HBC dominance in lands that became American territory. Oregon Territory created as a political unit of the United States in 1848, Vancouver Island was created as an HBC colony in 1849, and British Columbia was created as a colony in 1858—actions which marked an end to fur-trade dominance and the beginnings of settler-dominated societies in the region. |

Fort Vancouver, (right). Sketched by Captain H. Warre, (1819–1898). The flag visible here is actually the Hudson's Bay Company flag. From Warre, Henry James, Sketches in North America and the Oregon Territory. London, Dickinson & Co., 1848. Plate 12.

Fort Vancouver, (below). (Reports of Explorations and Surveys, to ascertain the most practicable and economic route for a railroad from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean, made under the direction of the Secretary of War in 1854-5. Washington, D.C., 1857. Vol. 12, pt. 1. plates 42 and 44. Sketches by J. M. Stanley, 1853.)

Fur traders were not the same as settlers in that they did not come to establish permanent towns and farms or to dispossess Indians from their lands. But the land-based fur trade did lay the foundations for the settlement that ensued in the Pacific Northwest and western Canada after 1840. Like the maritime explorers and traders, land-based traders scouted the coastline and developed relationships with Indians west of the Cascades. They also expanded European and American activities inland. Fur traders explored virtually all corners of the American Northwest and Canadian West; organized systems of trade and travel across these regions; and pursued extensive and intricate relations with a variety of Indians. Moreover, operating out of a headquarters at Fort Vancouver (in what would become Washington state), fur traders explored southward as far as California and eastward as far as Utah. Furs from the entire Far West of North America made their way to Asian and European markets by way of the Columbia River and the Pacific Northwest. Reinforcing the pattern established by the maritime fur trade, the land-based fur trade linked the Pacific Northwest as a resource hinterland to markets across the globe.

Fort Walla Walla, (left).

The companies that dominated this trade were British. An American firm, the Pacific Fur Company of John Jacob Astor, attempted to conduct trading at posts along the Columbia River between 1811 and 1813, but it lacked the financial resources and national support required to succeed. Moreover, most of Astor's employees were Canadians whose experience in the fur trade came from working for British rivals, especially the North West Company of Montreal. Thus it was no difficult thing for the Astorians to sell out to the North West Company in 1813 and go to work for the British competitor. (A good book on the Pacific Fur Company is James P. Ronda, Astoria and Empire [1990]).

The presence of the North West Company beyond the Rockies reflected the intensity of the business competition in the Canadian fur trade during the later 18th and early 19th century. Since early colonial times in British North America, commerce in furs had been instrumental in pushing Europeans westward into the continent, as rivals in the trade competed with one another to get the best and least expensive supply of pelts. Driven by business rivalries, fur traders explored new territory, developed relations with native groups, devised networks of trade and transportation, and claimed land for their respective nations. With the expulsion of France from North America in 1763 after the Seven Years War and the breakaway of the United States from Great Britain after 1776, much of the competition for fur in the North American Far West narrowed to a contest between the Hudson's Bay Company or HBC (a London-based monopoly with its North American headquarters on Hudson Bay in northern Canada) and the North West Company or NWC (a Montreal-based firm, employing many French Canadians, which emerged out of chaotic competition among smaller firms during the 1770s and 1780s). With a royally granted monopoly on commerce in all watersheds draining into Hudson Bay, the HBC had a tremendous natural advantage over the NWC, which had no such privilege and which had to compete against the HBC's much lower overhead. In response, the NWC became much the aggressor in pushing westward in search of new, cheaper supplies of fur and a Pacific-coast outlet that would enable it to export its furs to market efficiently. The company's aggressiveness took a number of forms in the Pacific Northwest, including dispatching Alexander Mackenzie (1793), Simon Fraser (1806-1808), and David Thompson (1807-1812) to explore the far western region and establish trading posts there, and being on hand during the War of 1812 to take over the Pacific Fur Company operations at Astoria and along the Columbia River. Thereafter, the British prevailed among the powers competing for control in the region.

In 1821, the North West Company was absorbed by the Hudson's Bay Company because the British government forced the two firms to merge in order to bring a halt to their bitter competition. The HBC had never operated beyond the Rocky Mountains, so the merger basically pushed it into a role of substantial influence in a region with which it was unfamiliar. The Company adjusted rather promptly, however, to the opportunity, creating a fur-trading district that became known as the Columbia Department. It established a series of posts, refined means of trading and trapping for the furs, laid out networks of transportation, cultivated relations with Indians, and in general made the Columbia a profitable branch of the fur business. The HBC went further than this, however. It also initiated the first systematic, non-Indian logging, fishing, farming, and stock-raising in the Pacific Northwest and Canadian West—partly to provide itself with supplies and partly to trade the surplus product to markets in California, Hawaii, Alaska, and around the Pacific Rim. Links between this corner of North America and the rest of the world were once again strengthened, as was the region's identity as a place from which raw materials were extracted and shipped to the rest of the world.

Under the Hudson's Bay Company, then, the "fur trade" of the Pacific Northwest became much more than a trade in furs. Such a redevelopment represented the culmination of a series of business decisions made by HBC officials, and in particular George Simpson. These decisions represented, in a sense, the adaptation of the fur trade to a new North American environment. When the NWC and HBC moved their operations beyond the Rockies, they entered a region quite unlike what they had known in the East, and they had to change their ways. NWC and HBC officers encouraged several innovations. They increasingly shipped furs to market via the Pacific coast, rather than via Hudson Bay or Montreal, using the Columbia as their main artery of transportation. They replaced their birch-bark canoes with either canoes made of cedar (following the example of Northwest Indians) or pack trains of horses (which were also generally obtained in trade from Northwest Indians, especially the Nez Perce). They substituted salmon (at first reluctantly) for the pemmican (a preserved mixture of bison meat and grease) on which they had relied as a food staple east of the Rockies. And in regions south and east of the Columbia, they took to hunting fur-bearing animals themselves, in annual trapping expeditions, because the natives in those areas were less willing than Indians back east to hunt animals for the fur trade.

A hunting party (above) of Nez Perce Indians meeting with survey members near the Bitter Root River. (Reports of Explorations and Surveys. Washington, D.C., 1857. Vol. 12, pt. 1. plate 33. Sketch by J. M. Stanley, 1853.)

These adaptations occurred under the reign of both the NWC and the HBC, but it was the latter company that truly redefined the fur trade for in the Pacific Northwest. The Hudson's Bay Company was a remarkably well-organized firm with considerable powers in fur country. As a monopoly company chartered by the King of England, the HBC held some legal and judicial authority over the lands in which it operated, for example. Most importantly, as a monopoly it was capable of keeping British settlers out of and away from the lands from which it was extracting furs. It possessed a strong sense of discipline and order, and it demonstrated the ability to follow a long-term strategy in carrying out its operations. No doubt the individual most responsible for ensuring HBC economic success was George Simpson, who oversaw the operation of the Columbia Department for the London-based company.

Simpson made three tours of the Columbia Department, and with each visit he reorganized the trade in the area. On his first trip of 1824-25 (recorded in a journal, an excerpt of which makes up part of the reading for this unit), Simpson ordered changes that heightened the efficiency of the business, extended the trade so as to extract more fur and deflect American competitors, and insisted that traders in the region become more self-sufficient in order to reduce overhead expenses. On his second visit of 1828-29 Simpson, recognizing that the region's milder climate and natural resources offered opportunities not available elsewhere in the fur country, called for economic diversification that led to such things as exporting lumber, preserved salmon, and produce to Pacific markets in California, Hawaii, and Alaska. These changes made the Columbia Department one of the most profitable parts of the fur trade. On a third visit during 1841-42, Simpson reorganized the trade a third time, this time moving the majority of HBC operations northward in anticipation of losing the southern part of the Columbia Department to the United States. In this phase, a fort at Victoria replaced Fort Vancouver on the Columbia as the headquarters of the Department.

George Simpson in the 1850s, (right). (In Galbraith, The Little Emperor. Toronto, 1976. Originally a daguerreotype; copy made by Notman in 1872. Photo credited to the Notman Photographic Archives, McCord Museum of Canadian History.)

One of Simpson's key concerns throughout these decades was the threat of competition from the United States. He worried that American fur traders, operating in the Rocky Mountains, might move into the Northwest and compete against the HBC (the HBC's monopoly applied only to other British enterprises), and took many measures to keep these competitors at bay. One such measure was a "scorched-earth" policy, whereby HBC expeditions (in contrast to company policy elsewhere) purposely left no beaver in the watersheds they trapped south and east of the Columbia River, so that there would be nothing to lure American fur trappers to the Northwest. Simpson also worried that American settlers might decide to move to the lands of the Columbia Department, not to trade fur but to establish homes and farms, towns and industries. These concerns of Simpson became apparent in 1829 when he interviewed an American fur trapper, Jedediah Smith, whose party had come to the Oregon Country. Simpson interrogated Smith about whether Americans were interested in the Northwest or might be planning to migrate there. Smith assured Simpson that the Northwest was too remote from the states and too difficult to get to for Americans. Simpson apparently accepted Smith's answers at face value. At the same time, however, Smith was composing a letter to U.S. Secretary of War—a letter which later became a report to Congress—that spoke of the attractions of the Northwest for settlers and of the ease with which overland migrants could travel to the region via South Pass in the Rocky Mountains.

George Simpson, (left). (University of Washington Special Collections, Portrait Files.)

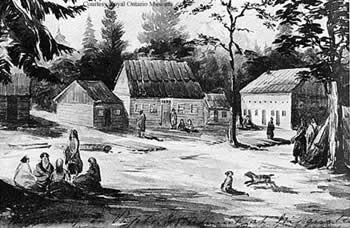

View of Nisqually Farm, 1845, (right). (Sketch by Henry Warre. Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto. Reprinted in James R. Gibson, Farming the Frontier: The Agricultural Opening of the Oregon Country, 1786-1848. Seattle, University of Washington Press, 1985. p.100.)

View of Nisqually Farm, 1845, (right). (Sketch by Henry Warre. Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto. Reprinted in James R. Gibson, Farming the Frontier: The Agricultural Opening of the Oregon Country, 1786-1848. Seattle, University of Washington Press, 1985. p.100.)

Although he did not say so to Simpson, Smith envisioned American settlers arriving and claiming the Oregon Country—or at least parts of it—for the United States. Simpson was perhaps inclined to accept Smith's deceitful answers because the focus of his company's concern was extractive industry, not settlement. Smith, representing Americans with many interests in the Far West besides fur, was interested in all the different kinds of economic opportunities that the Northwest offered. Simpson, by contrast, working for a commercially oriented company, had a harder time grasping why Smith and other Americans might regard the region as a desirable destination. William H. Goetzmann, in Exploration and Empire (1966), explains that the kind of information Smith passed along to Americans back east "inspired migration, and made settlement in the Far West seem possible. It was not the kind of information," however, "that Simpson and the other Hudson's Bay leaders received from their own men, nor was it the information they really desired to hear." Goetzmann concludes that, for all their accomplishments in the Far West, the British fur traders were more agents of commerce than they were agents of empire. Their focus was narrower—on the profits to be made from fur and other extracted commodities—and did not envision the settlement of the Oregon Country or its incorporation into the political mainstream of the nation. Americans, by contrast, had more diverse visions for the region—ones that included not only the fur trade but also many other activities—and by the 1840s, after a period of HBC hegemony, they were increasingly capable of asserting their visions in the region. No doubt their interest was heightened by Smith's mention of the many commodities besides fur that the HBC produced in the Columbia Department. Without knowing it and without intending to, the HBC was through its program of economic diversification advertising the resources and fertility of the Northwest to future American settlers.

| Course Home | Previous Lesson | Next Lesson |