Lesson Twenty-seven: Extinction in Ecotopia

Environment and Identity in the Late-20th-Century Pacific Northwest

In 1975 a Berkeley writer named Ernest Callenbach published the novel Ecotopia. Set twenty-four years into the future, in 1999, the book portrayed how a part of the United States—northern California, Oregon, and Washington—had seceded from the rest of the country in 1980 and established the new country of "Ecotopia," an ecological utopia. The fictional new nation outlawed the internal combustion engine, did away with most cars, replaced many city streets with streams, and planted flowers in potholes. It prided itself on a "steady-state" (or no-growth) economy that recycled virtually all wastes, ran on solar power, and reduced the work week to 20 hours. The standard of living declined, but most Ecotopians did not seem to mind. They lowered their material expectations, found ways to enjoy their newfound leisure time, and derived more happiness from living harmoniously with nature. They became better-rounded people; men in particular got more in touch with their "feminine" sides. Indeed, women's influence was critical in redirecting and running the society.

Cover of Ecotopia (above). (Courtesy of Ernest Callenbach, Ecotopia, Berkeley: 1975). The green land and falling water of "Cascadia" (below). Marymere Falls in the Olympic National Park near Lake Crescent. (Special Collections, University of Washington, Postcard Collection Photo by W. Ray Scott. Published by National Parks Concessions, Inc., Olympic National Park)

Cover of Ecotopia (above). (Courtesy of Ernest Callenbach, Ecotopia, Berkeley: 1975). The green land and falling water of "Cascadia" (below). Marymere Falls in the Olympic National Park near Lake Crescent. (Special Collections, University of Washington, Postcard Collection Photo by W. Ray Scott. Published by National Parks Concessions, Inc., Olympic National Park)

Ecotopia is not great fiction. For one thing, it tends to read as a male fantasy about the benefits of feminism. For another, there is at least one glaring contradiction in the approach of Ecotopians that needs better explanation: in order to attain their independence, the radical environmentalists used nuclear blackmail by threatening to detonate atomic bombs in major American cities if they were not granted their autonomy. Many observers concurred that, as a work of fiction, Ecotopia left something to be desired. Twenty-five publishers rejected the manuscript before it was issued by a Berkeley collective, Banyan Tree Books. Yet the novel began to attract adherents and sold amazingly well, so well that it was brought out as a Bantam paperback and sold thousands and thousands of copies. Readers perhaps regarded the novel not as good fiction but as a kind of wishful nonfiction, a forecast of how the future could or should evolve. (Bantam now markets the novel as one in a series of "Bantam New Age Books: A Search for Meaning, Growth and Change.")

Ecotopia was especially popular among readers in the Pacific Northwest. As late as 1979, when the novel was still selling at a rate of 1,000 copies every month, Callenbach estimated that at least half of the sales took place in the Pacific Northwest. The plot possessed a certain resonance for people in Oregon and Washington. The idea that the American Northwest was some kind of ecological utopia gained popularity outside the region as well. In 1979 the British magazine New Scientist labeled the Pacific Northwest "ecotopia." Then in 1981 the journalist Joel Garreau published a trendy book called The Nine Nations of North America. Garreau asked readers to put aside old political boundaries and recognize the new geographical and cultural realities remaking North America into different states. These included Mexamerica (Mexico and the American Southwest), Quebec (separated from the rest of Canada), the Foundry (the industrial Northeast), the Empty Quarter (most of western Canada and the American Great Basin and Rocky Mountains), and Ecotopia (the coastal strip running from Monterey, California to Anchorage, Alaska, including the western half of the Pacific Northwest). Garreau argued that, in some measure, Callenbach's Ecotopia was coming into existence in northwestern California, coastal Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia, and southeastern Alaska.

By the 1990s, the notion of cross-border, ecotopian region, distinct from the rest of North America and shaped in large part by a special relationship to nature, persisted in the form of "Cascadia," a territory conceived as running roughly from Eugene, Oregon to Vancouver, B.C. Boosters of Cascadia included mainstream businessmen, academics, and politicians as well as more countercultural environmentalists and visionaries. Agendas for Cascadia varied widely, from free-trade across the 49th parallel to environmental protections of the highest order, so its promoters seldom saw eye to eye. But they tended to agree that the far American Northwest and far Canadian Southwest shared some fundamental cultural traits, including a Pacific-Rim outlook as well as key environmentalist attitudes, and the same verdant and well-watered environs. In 1992 Paul Schell (a King County developer, academic, and politician who was elected mayor of Seattle in 1997) explained that Cascadia implied a relatively well-preserved and well-appreciated natural setting inhabited by people "with a love of the outdoors and reverence for the environment passed to us from native people." Another promoter of the idea, David McCloskey, depicts Cascadia as "a great green land on the northeast Pacific Rim," "one of the newest and most diverse places on earth," and "a land of falling waters."

The ideas of Ecotopia and Cascadia were to a significant extent exceptionalist. They viewed one particular corner of North America as a special region, and intimated that the various parts of it (including those on either side of the international boundary) had more in common with one another than they did with the rest of their respective nations. Callenbach carried exceptionalism to its logical conclusion by portraying Ecotopia as independent from the rest of the United States. To a limited extent, art was imitating life in Callenbach's novel, because during the early 1970s residents of Oregon had begun their own separatist campaign by trying to persuade migrants from California and elsewhere not to move to their state. Oregonians were in one sense tilting at windmills, because the law of the land prohibits one state from excluding those from another. Moreover, the campaign was, for some, merely a clever way to call attention to environmental problems. The anti-Californian effort also came couched in humor: Oregonians attempted to discourage newcomers with jokes about the high annual rainfall, the state bird being the mosquito, and the state animal being the earth worm. The governor promised to erect a "Plywood Curtain" to keep Californians out, and bumper stickers read "Don't Californicate Oregon" and "Keep Oregon Green, Clean—and Lean."

Governor Tom McCall presenting an environmental award to Richard Chambers, who was the mind behind Oregon's bottle bill. (In Brent Walth, Fire at Eden's Gate, Portland, 1994, p. 255. Photo by Joseph V. Tompkins and courtesy of the Chambers family.)

Governor Tom McCall presenting an environmental award to Richard Chambers, who was the mind behind Oregon's bottle bill. (In Brent Walth, Fire at Eden's Gate, Portland, 1994, p. 255. Photo by Joseph V. Tompkins and courtesy of the Chambers family.)

But numerous Oregonians were quite serious about the campaign. They held Californians to blame for many of the environmental problems associated with growth in Oregon, and they hoped to alleviate those problems by discouraging in-migration. Not all Oregonians joined the effort: A groups of business and labor leaders founded the Western Environmental Trade Association in 1971 to combat the "environmental hysteria" or "environmental McCarthyism" that they feared would undermine Oregon's economy. But the anti-Californian attitudes persisted. In the 1980s and 1990s, many in Washington and Idaho came to join Oregonians in their hostile attitudes toward Californians, assigning to refugees from the Golden State a disproportionate share of the blame for the environmental (as well as social and economic) problems of the Northwest. (See Lesson 1.) They shared the Ecotopian or Cascadian sense that their region was exceptional, because of its environment and because of its residents' desire to protect that environment, and they worried that the influx of outsiders—particularly from the Golden State—endangered what was distinctive about the Northwest.

The anti-California campaign, although highly visible, was hardly the main achievement of regional environmentalism. Just as a spate of political reforms had made Oregon into America's "Laboratory for Democracy" in the progressive era, during the later 1960s and the 1970s the state led the nation in implementing new environmental reforms. Led by Republican Governor Tom McCall (1967-75), it (among other things) cleaned up the Willamette River and created an adjacent "greenway"; instituted a state department of environmental quality; passed a law requiring minimum deposits on beverage bottles and cans; protected parts of six streams in the state as "wild" rivers; expanded the state park system (while setting aside a percentage of campsites for Oregon residents only); and developed a far-reaching land-use planning system that created urban-growth boundaries and mandated that cities and counties formulate comprehensive plans to comply with state land-use guidelines. Washington proved more reluctant to pass environmental reforms (the state turned down "bottle bills" in 1970 and 1982, for instance), but beginning under another Republican Governor, Dan Evans (1965-77), it followed a similar path. The Northwest was relatively progressive in terms of environmental reform (although Idaho lagged behind the other states), even if it did not entirely live up to the "ecotopian" label.

Given the Northwest's ecological sensitivities, then, it seems quite paradoxical that during the 1980s and 1990s there emerged in the region two well-publicized environmental crises that flatly contradicted its green reputation. Both crises revolved around the question of endangered species, with the two animals in question—the northern spotted owl and assorted runs of salmon and steelhead—serving as indicator species for the health of much broader ecosystems (the old-growth forests in the case of the owls, and riverine watersheds, among other things, in the case of salmon). That these crises would emerge among such an environmentally progressive people—that extinction could flourish in Ecotopia—requires some explanation. How could ecological catastrophe occur in ecotopian Oregon and Washington? Was the Northwest's environmental reputation fraudulent?

The traditional ethos of growth is documented in the original caption printed with this view of a logging truck (right): "One of the most thrilling sights in the West is these large diesel trucks hauling logs on mountain roads." (Special Collections, University of Washington, Postcard Collection Pub. by Eastman's Studios, Susanville, California).

The outdoors as playground (left), and the urban focus of the environmental movement is prevalent in this image of family picnicking at Ediz Hook near Port Angeles. (Special Collections, University of Washington. Photo credited to the Washington State Department of Commerce and Economic Development.)

The outdoors as playground (left), and the urban focus of the environmental movement is prevalent in this image of family picnicking at Ediz Hook near Port Angeles. (Special Collections, University of Washington. Photo credited to the Washington State Department of Commerce and Economic Development.)

One thing to keep in mind is that ecological crises occur in part because people perceive them occurring and give them attention. The issues surrounding spotted owls or runs of salmon and steelhead, which may well have received less attention elsewhere, became prominent in the Pacific Northwest in part because of the environmentalist orientation of residents there (and especially those urban residents who lived at some remove from downturns in the timber and fishing industries, and saw the outdoors as a playground rather than a place to make a living). In other words, the population's awareness of ecological issues helped to ensure that the crises occurred. It also seems important to recall that threats to owls and fish were due in no small part to forces external to the Pacific Northwest. The practices of Japanese fishermen, for example, the weather pattern of El Nino, or federal policies regarding the cutting of timber in National Forests were all largely beyond the control of people in the region. In some ways, then, the fight to preserve owls and fish was a fight to assert control over the region. But it was also more than that. Although Northwesterners were not entirely to blame for the environmental crises of the 1980s and 1990s, they had contributed enormously to them. If inhabitants of the region were environmentally progressive during the late 20th century, they had also encouraged the very problems that so occupied their attention.

To account for the contradictory phenomenon of extinction in ecotopia, it helps to place the problem into historical perspective. The widespread ecological awareness that made the spotted-owl and salmon crises possible was relatively recent. Congress passed the Endangered Species Act in 1973, and average people only thereafter began to appreciate widely the value of biodiversity. As Expo '74 in Spokane had demonstrated all too well, a comprehensive environmental movement was rather new in North America. Moreover, although that movement enjoyed considerable success in the Pacific Northwest, it also encountered there a deeply rooted set of values that at many points ran counter to it. These values revolved around the traditional ethos of economic and demographic growth based in large part on extraction of such natural resources as trees and fish. Environmentalists lamented that it took so long to effect change and worried that any delays in implementing reform threatened the survival of species and entire ecosystem. Yet the reforms they sometimes proposed-like stopping all timber-cutting and road-building in federal forests, and removing certain dams from rivers-were the functional equivalent of stomping on the brakes and putting the regional economy into a dangerous skid. The environmental writer Barry Lopez, writing in Old Oregon (Autumn 1991), summarized the situation with words those spoke well to the Pacific Northwest: "One of our deepest frustrations as a culture, I think, must be that we have made so extreme an investment in mining the continent, created such an infrastructure of nearly endless jobs predicated on the removal and distribution of trees, water, minerals, plants, and oil, that we cannot imagine stopping."

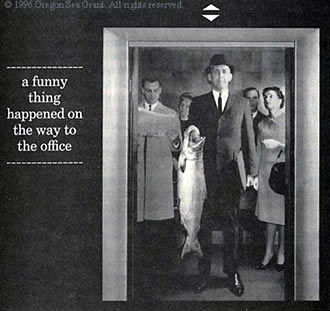

Salmon in the City (right). "Come to Oregon where the market is growing and the living is fun," said the headline to this 1963 advertisement run by Portland General Electric Co. in Fortune magazine. The ad explicitly linked salmon to the quality of life that would attract a business executive to the Northwest: "Mr. Carlson is a nut on fishing. He can . . . drive 20 minutes from his home in the heart of Portland and spend a couple of hours trying to latch onto a salmon and still be in the office by 9." (Caption & photograph in Joseph Cone and Sandy Ridlington, eds., The Northwest Salmon Crisis. Corvallis: Oregon Sea Grant, 1996.)

The peculiar juxtaposition of extinction and Ecotopia resulted from a collision between two different impulses, or maybe two different eras. Ecological consciousness took hold before the old ethos of growth had really given way. The endangered-species crises of the 1980s and 1990s attested to the regional turning point. In our readings, William Dietrich covers the spotted-owl controversy in Final Forest. Here, the destruction of wild runs of salmon on Northwest rivers can illustrate how one period of history ran into another. [An historical introduction to the topic is Joseph Cone and Sandy Ridlington, eds., The Northwest Salmon Crisis: A Documentary History (Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 1996). See also Richard White, The Organic Machine: The Remaking of the Columbia River (New York: Hill and Wang, 1995), and Charles F. Wilkinson, Crossing the Next Meridian: Land, Water, and the Future of the West (Washington, D.C.: Island Press, 1992), ch. 5.] It is estimated that prehistoric runs of salmon and steelhead on the Columbia River numbered as many as 11 to 16 million fish annually, and that Indians caught as many as 42 million pounds every year without depleting the resource. By the later 19th century, non-Indians began commercial fishing on the river in earnest; in 1883 they harvested 43 million pounds of one species alone-the Chinook salmon. Thereafter the states and federal government began to regulate the fishery and to build hatcheries so as to propagate fish artificially. Yet the numbers of fish returning each year fell fairly steadily. Over-harvesting was one part of the problem (see Lesson 14), but destruction of salmon habitat-resulting from logging, farming, dams, and other things-was another. Northwesterners got increasingly alarmed about the declining Columbia fishery, but until the late 20th century they generally were not alarmed enough to do a lot about protecting it. By the late 1980s, eighteen different (locally distinct) stocks of salmon were extinct on smaller rivers and tributaries of the Columbia. In the early 1990s the number of returning fish had fallen to 2.5 million per year, and the annual catch had fallen to 5-8 million pounds. Each year brings more listings of threatened or endangered species, and more abbreviations or cancellations of fishing seasons. Each year also brings more proposals (at escalating costs) to "solve" the problem.

Industry along the Columbia River also contributed to the salmon crisis. This view shows the Long-Bell industrial development at Longview (below) while still under construction in 1924. (Special Collections, University of Washington, Long-Bell photo #1624, neg. #4461.)

On the surface it would seem that addressing the salmon crisis would be easier than addressing the spotted-owl problem. Wild salmon have a wider range of supporters, many of whom regard the fish as the critical icon of the Pacific Northwest. But in fact the threats to wild salmon come from things that are, even more than old-growth timber, fundamental to the political economy of the modern Northwest. Threats to the survival of salmon stem from changes to nature that would prove very hard to reform or undo. The habitat supporting wild salmon, especially spawning, has been severely compromised by the welter of activities undertaken by people in the region. Logging is one example of a threat to the species; a stream in an old-growth forest is estimated to produce seven times the number of fish as that in a harvested forest. Farming and grazing also disturb and pollute rivers and streams; urbanization and industrialization compromise them further. Hatcheries appear to be another threat to wild stocks of salmon. They have been deemed essential for keeping the numbers of fish high enough to support commercial and recreational fishing interests, but they undermine wild runs of fish in a variety of ways. To close down hatcheries, however, could jeopardize what remains of the fishing industry.

On the surface it would seem that addressing the salmon crisis would be easier than addressing the spotted-owl problem. Wild salmon have a wider range of supporters, many of whom regard the fish as the critical icon of the Pacific Northwest. But in fact the threats to wild salmon come from things that are, even more than old-growth timber, fundamental to the political economy of the modern Northwest. Threats to the survival of salmon stem from changes to nature that would prove very hard to reform or undo. The habitat supporting wild salmon, especially spawning, has been severely compromised by the welter of activities undertaken by people in the region. Logging is one example of a threat to the species; a stream in an old-growth forest is estimated to produce seven times the number of fish as that in a harvested forest. Farming and grazing also disturb and pollute rivers and streams; urbanization and industrialization compromise them further. Hatcheries appear to be another threat to wild stocks of salmon. They have been deemed essential for keeping the numbers of fish high enough to support commercial and recreational fishing interests, but they undermine wild runs of fish in a variety of ways. To close down hatcheries, however, could jeopardize what remains of the fishing industry.

Dams on rivers present an even bigger obstacle to the survival of wild salmon and steelhead. In 1941 the main stem of the Columbia had three dams on it. Today it has fourteen, and the Snake River has ten. The entire watershed sports more than 400 dams, according to one account. On the main stem, salmon returning to spawn die at a rate of 13% on fish ladders at each of the four lower dams, and 5% or less at fish ladders on each of the upper dams. The downstream run for young salmon is even more deadly. Until quite recently, when efforts have been made to provide more water over the dams during spawning season, salmon headed toward the ocean died at the rate of 15% per dam (in years of especially low flow, the rate reached 35%). For every 1,000 salmon swimming downstream past eight different dams, 730 died along the way in an average year.

View of the hydroelectric power plant and dam on the Elwha River (right) near Port Angeles in 1914. (Photo by Asahel Curtis, neg. #28530, copy neg. Original neg, Washington State Historical Society, Tacoma.)

To date, solutions proposed for these high mortality rates have not reversed the decline. The Army Corps of Engineers, for example, loaded trucks with salmon fry on the Snake and upper Columbia, drove them downstream via Interstate 84, and released them below the last dam. The fish took a freeway to the ocean, and in doing so never learned very well the scent or shape of the river, which was essential for them to return and spawn. Spilling more water over the dams has seemed to help, but has not truly stemmed the decline. Now people have begun to speak seriously about taking down dams in order to restore salmon runs. That expensive solution seems workable on the Elwha River on the Olympic Peninsula, where the two existing dams are not essential to the local or regional economy. But dams elsewhere in the Northwest, especially on the Columbia system, are so integral to the regional economy that it is very hard to imagine what life would be like without them. They provide inexpensive electricity to power farms and industry as well as to heat and cool homes. (Nisqually Indian Billy Frank questions the idea of cheap hydroelectricity: "It's not cheap. It's all been paid for by the salmon. When these lights come on, a salmon comes flying out.") The dams provide water for irrigation, allowing arid parts of the Northwest to become big agricultural producers. They control floods and erosion along the river, make inland navigation possible as far upriver as Lewiston, Idaho, and offer such recreational opportunities as boating and water-skiing. So many interests throughout the region depend on and benefit from the dams so much that it is very difficult to imagine taking them down.

It is useful to keep in mind that the system of dams is itself a quite recent development. The last big dams on the Columbia and Snake were completed the late 1960s. That is to say, at the same time that the environmental movement was beginning to crest—a few years before Callenbach published Ecotopia—the system of river improvements, envisioned in the 1930s to reform regional society and recast the regional economy, was being "perfected." Just as the dams were finished and the benefits from the newest ones began to flow to those who had long awaited assistance from the Columbia Basin Project, environmentalists mounted new and sustained challenges to the dams. Their critique proved forceful, but it ran counter to what had been the basic thrust of regional society for more than a century. Since the 1840s Americans in the Northwest had been trying to harness nature in order to create wealth and transform the region into something more than a remote and isolated hinterland. Dams had helped to overcome the perpetual problem of economic underdevelopment in the Pacific Northwest. They represented, in a sense, the attainment of precisely what Americans had long wished for in the region. It may be possible, even desirable, to revise the goals for Northwest society and reverse course in order to protect salmon. But if the salmon cannot be saved, it may well be because the momentum of historical events for the last century or more has run in the opposite direction.

In the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s it became fashionable to lament the influx of Californians to the Pacific Northwest. Contrast this approach to that of the late 1940s. California experienced a drought in the years immediately after World War II. The shortage of water threatened farming in the Golden State, and some people there proposed pumping water from the Columbia River southward to help quench California's thirst. Two of the Northwest's leading newspapers, the Portland Oregonian and Seattle Times, had a different idea, one more in keeping with the region's pro-growth mentality and confidence in its projects to harness and use natural resources. "Why should not the people come to the water, instead of the water being transported...to the people? There are no barriers of which we are aware to the migration of [drought] refugees to the irrigable lands of Oregon and Washington, which are in easy reach of the great Columbia." This impulse—inviting outsiders to move to the region, to contribute to and benefit from the conquest of nature there—has dominated the history of the American Northwest. It remains to be seen whether another perspective, one emphasizing quality of environment more than quantity of growth, can or should truly supplant it.

Chuckanut Sunset (above): "Mona Lisa pale stuff in comparison," claimed this postcard writer while looking out at a Puget Sound sunset from Chuckanut Drive near Bellingham. (Special Collections, University of Washington, Postcard Collection. Photo by by Bert Long, Sr., published by Ellis Post Card Company, Arlington, Washington.)

| Course Home | Previous Lesson |