Lesson Eleven: Overview of American Indian Policies,

Treaties, and Reservations in the Northwest

Native Americans fishing for salmon. ("Salmon Fishing at Chenook" by James G. Swan, published in his The Northwest Coast; Or, Three Years' Residence in Washington Territory, New York, 1857)

|

The colonization of Indians by non-Indian society exemplified just how lines got drawn on the land in the Pacific Northwest. It was not a clear-cut or precise process, and it was not a process that was seen the same way by all the parties involved. Policy toward Native Americans in the Pacific Northwest was an extension of the Indian policy developed at the national level by the U.S. government. In other words, the rules and regulations for dealing with Indians were established and administered by various federal officials based in Washington, D.C.—by superintendents of Indian affairs and Army officers, by Senators and Congressmen, by members of presidential administrations and Supreme Court justices. Yet western settlers—the residents of states, territories, and localities—attempted with some success to modify national Indian policy to suit their own ends. Moreover, the natives who were the objects of these policies also attempted to modify and resist them, again with a limited degree of success.

To explain the development of relations between Indians and non-Indians in the Pacific Northwest, then, one needs to keep in mind that there were federal points of view, settler points of view, and native points of view. The plural—"points of view"—is deliberate. It is also crucial to keep in mind that there was no unified perspective among any of the parties involved. Neither the officials of federal government, nor the settlers of the Northwest, nor the Indians of the region were unanimous in their thinking about and responses to American Indian policy as it was applied in the Pacific Northwest. (Indians from the same band or tribe sometimes ended up fighting one another; some women proved more sympathetic to Indians than men did; the U.S. Army was often much more restrained in dealing with natives than settler militias were.) This lack of agreement was surely one of the things that complicated, and to some extent worsened, relations between Indians and non-Indians. It makes generalizations about those relations tenuous.

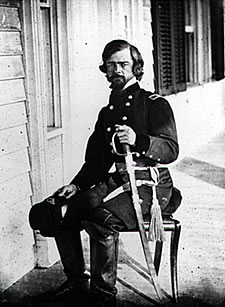

Joseph Lane (right). (Reproduced in Johansen and Gates, Empire of the Columbia, New York, 1957. Photo courtesy of Special Collections, University of Oregon Library.) Portrait of Isaac I. Stevens (below). The federal Office of Indian Affairs assigned to Stevens the task of carrying out the new reservation policy in Washington Territory. (Special Collections, University of Washington, Portrait files.)

Although it is risky, then, I want to offer the generalization that 19th-century America was an achieving, acquisitive, non-pluralistic, and ethnocentric society. It had tremendous confidence in its way of life, and particularly its political and economic systems, and it aspired to disseminate its ways to those who seemed in need of them or able to benefit from them—including Indians (and Mexicans and, at times, Canadians). The nation was tremendously expansive, in terms of both territory and economy. Its assorted political and economic blessings (at least for free, white, adult males) seemed both to justify and feed this expansionism. Thus expansion was viewed as both self-serving (it added to the material wealth of the country) and altruistic (it spread American democracy and capitalism to those without them). The nation's self-interest was thus perceived to coincide with its sense of mission and idealism.

American Indian policy bespoke this mixture of idealism and self-interest. White Americans proposed to dispossess natives and transform their cultures, and the vast majority of them remained confident throughout the century that these changes would be best for all concerned. Anglo-American society would take from Indians the land and other natural resources that would permit it to thrive, while Indians would in theory absorb the superior ways of white culture, including Christianity, capitalism, and republican government. For the first half of the 19th century, federal officials pursued this exchange largely with an Indian policy dominated by the idea of removal. Removal policy aimed to relocate tribes from east of the Mississippi River on lands to the west, assuming that over time the natives would be acculturated to white ways. There were numerous problems with this policy, of course. For our purposes, one of the key problems was that removal policy regarded lands west of the Mississippi as "permanent Indian country." By the 1840s, numerous non-Indians were moving both on to and across those lands, ending any chance that they would truly remain "Indian country." By midcentury the Office of Indian Affairs had begun devising another policy based on the idea of reservations. This institution, new at the federal level, has had a central role in relations between Northwest Indians and non-Indians since 1850.

Reservations were designed to isolate, concentrate, and "civilize" Indians in a more intensive fashion that removal had done. Natives would be confined to a more restricted and rigidly defined space, supervised by white military and civilian officials, and taught the English language, farming and industry, and Christianity. The policy assumed that Indians would be "de-tribalized," i.e. they would give up their collective identity as part of a native group and adopt the more individualistic orientation of Anglo-America. Some whites doubted that reservations would succeed, and some saw them only as a place where natives might be able to die off in peace. But official policy remained optimistic that reserves would convert natives into Christian farmers who believed in private property, and participated in the market economy and democratic politics. Of course, official policy was made in Washington, D.C., where government employees were quite removed from the native groups whose lives they hoped to change. Moreover, in the mid-19th century the U.S. government was not nearly as powerful as it is today. Its ability to convey official policy all the way across the continent, to impose its wishes on settlers and natives—who had their own ideas about what was appropriate—was quite limited. Corruption in the Indian service further reduced the government's ability to secure its objectives, and so did constant changes in the design, administration, and funding of policy.

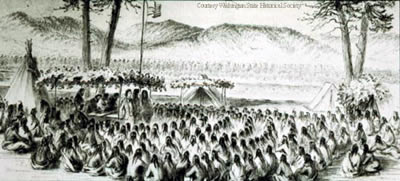

Isaac I. Stevens treaty council in the Bitterroot Valley, July 1855. (Drawing by Gustav Sohon. Courtesy of Washington State Historical Society. Reproduced in David L. Nicandri, Northwest Chiefs: Gustav Sohon's View of the 1855 Stevens Treaty Councils. Tacoma, 1986.)

Through the 1850s and 1860s, reservations in the Pacific Northwest were usually created by treaties signed between the United States and specific Indian groups. On the one hand, the treaties symbolized a significant amount of respect for natives. Apart from war, the government assumed that it needed to negotiate with Indian peoples, because it regarded bands or tribes as somewhat autonomous nations with clear rights to land and resources that non-Indians wanted. In theory, settlers were not supposed to be able to occupy land until the federal government had extinguished Indian title to it, either by treaty or by war (or, in the case of California, by taking the land over from another nation which, the U.S. assumed, had already extinguished Indian land titles). Treaties, then, were agreements or contracts between two political entities, each of which possessed a certain standing in the realm of diplomacy. That the U.S. government felt compelled to sign treaties suggests that, officially, it meant to treat Indian peoples with a measure of respect.

For many practical purposes, however, the treaty system proved cumbersome and unreliable. For example, it could take years before agreements reached between government agents and Indian groups were ratified; some treaties, indeed, were rejected by the Senate. So parties who signed treaties often did not know for long periods of time whether they would become the law of the land; yet, in Washington Territory, Indians who signed treaties were immediately directed to begin living as if they were in force. Moreover, neither the U.S. government nor the Indian groups consistently behaved according to the terms of the treaties that they signed and ratified. In the later 20th century, Indians have had remarkable success in the courts at getting the states and nation to live up to the terms of treaties that were signed in the 19th century. Their legal victories remind us that the treaties helped to preserve crucial rights for native groups. As Alexandra Harmon suggests in the accompanying article "Lines in Sand," furthermore, the treaties represented something like founding documents for many Indian groups, who previously had not regarded themselves as the kind of political entities—"tribes"—that the treaties assumed existed very clearly. That the benefits of this new status were realized only belatedly, often after much 20th-century litigation, suggests the difficulties that Indians faced in getting non-Indian society to honor the often contested terms of the agreements.

Even before Isaac Stevens began his treaty negotiations, the United States Army—anticipating conflicts between white settlers and Native Americans — established a military presence throughout Washington Territory. Fort Steilacoom, shown here in an 1880s photograph, was established in 1849. Pierce County settlers fled to the protection of this fort when hostilities broke out in 1855. (Special Collections, University of Washington, Fort Steilacoom file. Photo by Thomas H. Rutter.)

Although native peoples benefited in some ways from treaties over the long term, the treaty system proved quite disruptive, confusing, and destructive when imposed on Indians in the Pacific Northwest during the 1850s and 1860s. Native peoples had little or no experience with the legal ideas behind the treaties that they were signing; it is not clear how well they grasped the significance of the documents before them. Treaty negotiations, furthermore, were conducted primarily in the Chinook jargon, a trade patois of some 300 words and phrases which was not well suited for conveying the concepts needed for a clear understanding of the contractual documents being negotiated. There is also serious doubt whether most Indians believed that they had been suitably represented in treaty negotiations. Whites tended to assume that the "chiefs" who signed treaties spoke for entire tribes; yet white leaders also tried to recruit to the negotiations individual Indians who were regarded as more sympathetic to U.S. aims, and made fewer provisions for Indians who dissented. Government officials had one idea of how the politics of treaties worked, in other words, but it is not clear that Indians shared that idea. In short, the signing of treaties left a great deal of room for confusion and discontent. It is no wonder that the treaties of 1854-1855 in Washington Territory did not prevent the hostilities of 1855-58; indeed, in some regards they clearly helped to precipitate those hostilities.

No doubt for Indians the most disturbing aspect of treaties was the fact that they ended up being assigned to reservations. Reservations implied a variety of unwanted changes for native peoples. The most important change was that they were frequently being asked, or forced, to move away from their homes on to lands with which they were not familiar, giving up forever the majority of their territory to non-Indians. Some groups, such as the Makah and the Yakama tribes, were able to sign treaties that guaranteed them continued access to substantial portions of their homelands. These groups still lost ground, literally and figuratively, but perhaps their dislocation was not as severe. Also, treaties generally permitted natives to leave reservations for the purpose of finding food and work elsewhere. In many places, then, Indians became a critical part of the labor force in the Pacific Northwest after 1850, and many natives seized upon opportunities provided by the non-Indian economy to promote their own economic and cultural agendas. Nonetheless, the treaties and reservations implied drastic changes that were created on non-Indians' terms; natives found themselves now having to react and respond to the initiatives of outsiders who generally viewed Indians as inferior, child-like, and needing to be "civilized."

The Puyallup Indians, along with the Makah and Yakima tribes, were assigned lands close to their native villages and fishing places. Show here is Yelm Jim's house (right) and fish trap located on the Puyallup River, c. 1885. (Special Collections, University of Washington. Photo by Mitchell, WA, UW neg NA695)

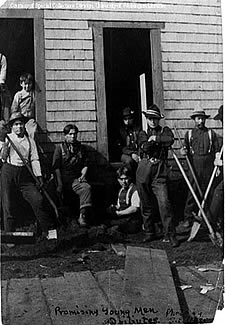

Posed in American dress and the proper tools, these Quiliute men (left) were described by their photographer as "promising young men." The view was taken by 1920, just before Indian policy began to change to allow Native Americans the opportunity to preserve their traditional culture. (Special Collections, University of Washington. Photo by Sarah E. Ober, UW negative #NA650.)

Relocation to reserves took Indians away from sacred sites and burial places. It also removed them from the natural environments that they had exploited for subsistence, and made them increasingly dependent on the government for food and other supplies. It frequently required Indians to live next door to other groups, including natives who had been their enemies, and in some cases Indian groups made life more miserable by mistreating one another on reservations. One reason that some of the Modoc Indians of northern California left the reservation and went to war in 1872-73 to remain on their homeland, for example, was that they were abused on the Klamath reservation in southern Oregon by another tribe. Finally, of course, the biggest changes expected of Indians on reservations were those insisted upon by the U.S. Office of Indian Affairs, which aimed to replace native cultures with Anglo-American ways by converting Indians into English-speaking, Christian, capitalist, farm families. Natives were asked to yield the majority of their lands as well as virtually all of their cultures. The pressures thus exerted against them by the U.S. government, especially when combined with the continuing ravages of disease and the mistreatment by settlers, proved enormous. The wonder is not, then, that some wars and a considerable amount of crime broke out between Indians and non-Indians in the Pacific Northwest between 1850 and 1880, but rather that more conflict did not occur.

Let me sum up how U.S. Indian policy was ideally meant to work in the later 19th century. First, the U.S. government would arrive in a new country and extinguish Indian title to land, preferably by treaties which represented lasting and binding contracts clearly understood by both parties. The government would then survey the land and make it available to non-Indian settlers, who would only then arrive to take up the land that Indians had yielded. The natives, having moved on to reservations, would proceed to be acculturated to Anglo-American ways; some officials even envisioned the full assimilation of Indians, which would make reservations unnecessary and result in their being disbanded. All of this would ultimately succeed, it was assumed, because Indians would ultimately see the wisdom of official policy and accede to it, and because the U.S. government possessed the power to make it work.

Of course, reality intruded upon this ideal scenario at many points and belied the assumptions that underlay it. The federal government did not arrive in the new country first, extinguish Indian title, and survey the land; settlers preceded them to the Northwest, so that U.S. officials were generally imposing their policies on places where Indians and whites had been mingling for decades. The federal government did not possess the power to enforce Indian policy as it was ideally constituted, live up to the treaties that it signed, or prevent settlers from upsetting relations with natives. Reservations did not become a satisfactory new home for Indians and did not convert the majority of them to Anglo-American ways. And Indians themselves did not come to see the general wisdom and propriety of government policies and goals.

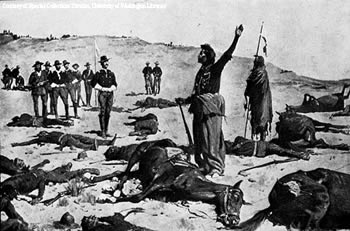

The Surrender of Chief Joseph, 1877.

The system did not work smoothly at all and, as it failed to achieve its goals, government tried to reform it and heighten pressure on Indians. By the 1870s, for example, it abandoned the treaty system, so that reservations would no longer be guaranteed by a binding contract. Thus the Colville Reservation in northeastern Washington, established by executive order in 1872, was reduced in size by about 50% during the 1890s by an act of Congress and an agreement with some of the chiefs on the reserve. In 1887, for another example, Congress passed the Dawes Act, which proposed to dismantle reservations by giving Indian residents individual allotments of land; the acculturation of natives would supposedly accelerate if they were forced to become individual owners of property and to abandon tribal affiliations on "collective" reserves. As a third and final example, after the Civil War and especially after 1880, the government relied increasingly upon boarding schools to accelerate the transformation of Indian culture. These institutions, which took native children away from their parents and homes and required that they speak English and dress like white people, epitomized the heightened pressure that the government placed on Indians, as well as the sense that solutions devised in the 1850s and 1860s had proven inadequate. Not until the 1920s and 1930s was the overall goal of transforming Indians into non-Indians reconsidered.

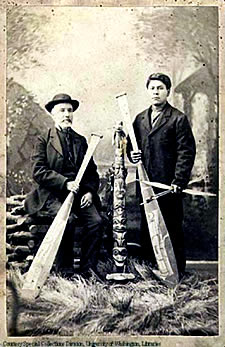

James G. Swan and his Haida interpreter, Johnny Kit Elswa. This picture was taken on a cruise to the Queen Charlotte Islands for the Smithsonian Institution, 1883. (Special Collections, University of Washington, portrait files)

To the north, in the territory that became British Columbia, non-Indians brought many of the same goals and methods to bear upon natives, and the experiences of conquest and dispossession were ultimately rather similar. However, there was a time in the 1850s when the approach of British agents offered a slightly different—and maybe slightly more sensitive—alternative. Indeed, within the American Northwest there existed a sense among some Indians that Canada provided a safer refuge. Consequently, the Yakama leader Kamiakin and the non-treaty Nez Perce leader Chief Joseph, in the 1850s and 1870s respectively, tried to escape north of the border during times of conflict with settler society.

Why was British Columbia different? Indian policy there during the 1850s rested in the hands of former Hudson's Bay Company employees, who had accumulated years of experience in dealing with Indians, rather than in the hands of distant federal officials. James Douglas, B.C. colonial governor through 1864, did things differently from how Isaac Stevens, governor of Washington Territory, did them. Whereas Stevens had to follow a national policy with often little regard for local needs and issues, Douglas was able to make local changes in policy and control some details himself. Douglas had the power, for instance, to write treaties and make them effective immediately, while Stevens had to wait for Senate ratification. In contrast to Stevens, who was urged to combine different Indian groups on the same reservations, Douglas tended to create more numerous and scattered reserves. This kept a larger number of native peoples on lands they considered their homes, and so reduced one key complaint that prevailed in Washington. B.C. natives also enjoyed more opportunity to purchase or homestead land. Finally, Douglas showed more restraint in dealing with native violence. He treated crimes as crimes by Indian individuals, as was less likely than Stevens to respond with military (as opposed to judicial) force.

A key difference between Washington Territory and early British Columbia helps to explain the divergent Indian policies — in American society the political leaders had to be more responsive to the anti-Indian attitudes of settlers. There were many fewer settlers in B.C. prior to the 1860s, which meant that there was less pressure on Douglas to accommodate their interests at the expense of Indians. (And once more Canadian settlers arrived, Indian policy turned harsher.)

Moreover, Douglas presided over a system where settlers' concerns were not as influential as those in the United States. Stevens worked in a political system that paid attention to the demands of citizens, especially the white male settlers who could vote and perhaps even advance the governor's political career. Douglas did not have similar pressures, in part because a more democratic system of government was not yet in place in British Columbia, so he could better afford to go against the popular preferences of settlers—something his former employer, the Hudson's Bay Company, had been doing for decades already.

| Course Home | Previous Lesson | Next Lesson |