The Klondike Gold Rush

Curriculum Materials for Washington Schools

Developed by

Kathryn Morse

Center for the Study of the Pacific Northwest

University of Washington Department of History

Curriculum Packet PDF

Table of Contents

|

III. Themes to Guide Discussion and Work |

VI. Chronology: Seattle and the Klondike Gold Rush VII. Bibliography: General Sources on Seattle and the Klondike

|

|

I. Introduction

The enclosed curriculum materials consist of a variety of original documents related to the Klondike gold rush and Seattle and a set of maps of the Pacific Northwest and Alaska. These materials are intended to provide students with an opportunity to learn about and investigate a specific topic in Washington history: How the Klondike/Alaska gold rush played a role in Seattle's economic growth and its rise to a position of economic dominance among Northwest cities. The materials also allow for the investigation of other topics as well, including the experience of men and women in the gold rush itself, in both Alaska and the Yukon Territory. Combined with a few other resources, these materials provide teachers with a focused curriculum unit on the Klondike and Seattle that combines history, geography, and literature, and adds an in-depth focus to the broader consideration of the history of trade and economic growth in the Pacific Northwest

The materials can be used in myriad ways. Most of the document "cards" or fragments, make reference to a particular place within the geography of the Northwest, the Yukon, and Alaska. The cards can thus be organized in reference to the maps. Students can start with the cards and find the places in question on the maps, and begin to understand what those places were like during the gold rush. They can also use the cards in tandem with the maps to follow miners into and out of the Yukon and Alaska, and get a firm grasp on the geography and natural features of the region. There are sources from miners who took different routes—Chilkoot Trail, White Pass Trail, Stikine River and Teslin Trail, and Yukon River. They can use the cards and the information from Klondike guidebooks to calculate the distances and costs involved in traveling to and outfitting for the goldfields, and gauge the methods of Seattle boosters in making Seattle a leading outfitting city. Outfitting lists and price lists provide a way for students to calculate just how much weight miners transported with them to the North, how far they had to travel, and what that travel entailed. The cards can then provide the basis for discussions, debates, and writing on the themes that emerge from the Klondike. Further suggestions are outlined below.

II. Historical Context

In the 19th century Seattle's economic development was curiously linked to gold. The California gold rush of 1849 created a sudden, large, and growing market for timber, and Seattle got its first rush of trade profits in shipping milled lumber south to the Bay Area and the Sierra goldfields. Gold discoveries in northern and eastern Washington drew more settlers north of Columbia in the 1850s and 1860s. A gold rush to the Fraser River in the 1850s, and a later one to the Cassiar region of British Columbia, drew many California miners to the Northwest, and formed the basis of a fledgling mining industry supplied by merchants in Victoria, Vancouver, and Seattle. Seattle remained a small, timber-oriented town, however. The growing community pinned its hopes for economic expansion on the coming of the intercontinental railroad, but the Northern Pacific foiled those hopes in 1883 by ending its tracks in Tacoma rather than Seattle. By that time Seattle and Tacoma had begun their long-standing rivalry over which would be the premier metropolis of Puget Sound, but Portland remained the larger, more influential trade center north of San Francisco.

In the 19th century Seattle's economic development was curiously linked to gold. The California gold rush of 1849 created a sudden, large, and growing market for timber, and Seattle got its first rush of trade profits in shipping milled lumber south to the Bay Area and the Sierra goldfields. Gold discoveries in northern and eastern Washington drew more settlers north of Columbia in the 1850s and 1860s. A gold rush to the Fraser River in the 1850s, and a later one to the Cassiar region of British Columbia, drew many California miners to the Northwest, and formed the basis of a fledgling mining industry supplied by merchants in Victoria, Vancouver, and Seattle. Seattle remained a small, timber-oriented town, however. The growing community pinned its hopes for economic expansion on the coming of the intercontinental railroad, but the Northern Pacific foiled those hopes in 1883 by ending its tracks in Tacoma rather than Seattle. By that time Seattle and Tacoma had begun their long-standing rivalry over which would be the premier metropolis of Puget Sound, but Portland remained the larger, more influential trade center north of San Francisco.

Seattle's prospects promised to rise, however, with the completion of a second railroad line, the Great Northern, from St. Paul to Seattle, in 1893. The completion of this second line, however, coincided with a severe economic panic, followed by a severe depression that lasted until 1897. At the moment that the railroad promised to open more and distant markets for Northwest timber, fish, and wheat, the national economy bottomed out. Unemployment soared in the Northwest, and around the country. Banks closed, and businesses failed.

Throughout the 1880s and early 1890s, a small number of gold prospectors and miners moved into and out of the Yukon River regions of the Yukon Territory and interior Alaska, making small gold strikes and moving from promising camp to promising camp. Alaskan villages, such as Circle City and Fortymile, were somewhat well known before the major strike along the Klondike River in 1896. The large, industrial Treadwell gold mine opened near Juneau well before the famous strike as well. Gold mining in the Yukon and Alaska was by no means an unheard of industry, and even in the depressed years of the mid-1890s, Seattle and other Northwest cities saw a few gold miners, and supplied them with food and equipment. In early 1896, months before the Klondike discoveries, miners showed up in Seattle in increasing numbers, taking passage for Circle City and Cook Inlet, following news of gold strikes.

Even this increasing gold-related trade did not promise Seattle anything in the way of a basis for sustained economic growth. In 1890, Seattle had a population of about 42,000 people. The city's economy had diversified in the 1870s and 1880s to include not only a small gold mining segment, but also coal mining, farming, wheat and fruit shipments, small manufacturing, dairy production, and a fishing industry that had moved north to include halibut and salmon fisheries in Alaska. But the timber industry, including a crucial shingle-production sector, remained the mainstay of the Washington, and the Seattle, economy.

In July of 1897, the steamer Portland arrived at Schwabacher's dock on the Seattle waterfront and discharged a horde of successful Klondike gold miners, weighed down with bags, sacks, and boxes of gold. The newspapers and telegraphs spread word of this shipment, and the similar one to San Francisco, all over the nation and the world. The depression-starved populace ate up the story. About 10,000 people in Seattle immediately decided to try their luck at the goldfields, and prepared to leave for the Klondike that summer. The immediate demand for mining supplies galvanized the grocers, clothing jobbers, and hardware mercantiles in the city. Several thousand people beyond Seattle arrived to look for work in the city, hoping to find jobs in the service economies fueled by the growing boom. Others flocked from all over the country to attempt to get to the northern interior before winter set in.

Within a few weeks of the arrival of the Klondike gold, the Seattle Chamber of Commerce met to come up with a plan for promoting Seattle as the outfitting center for the northern goldfields. The Chamber formed a Bureau of Information to advertise and publicize Seattle to the nation and the world at large, and to organize Seattle businessmen to join forces in this project. The Bureau of Information was led by its able and energetic secretary, an eastern newspaperman named Erastus Brainerd. The great fear, for Brainerd and other, was that another city, Portland or San Francisco, Vancouver or Victoria, would capture the prospective miners' attentions and draw them, and their business, to a city other than Seattle. Brainerd thus masterminded a huge media campaign designed to convince the whole country that Seattle was the one and only gateway city to Alaska. He used newspapers, letters, circular surveys, advertisements, an exhibit of gold, and petitions to the government to draw attention and business to Seattle.

The documents here include several items that pertain to the Seattle Chamber of Commerce's campaign to capture the Alaska trade, and thus to boost its own economic fortunes. There are several documents that show the competition between various cities for this trade. How do these cities still compete today? This connects to the larger Northwest history theme of how cities grow, and how they competed with each other to capture economic fortune. Seattle grew by becoming a center for trade with Northwestern hinterlands, which with the gold rush came to include Alaska. This can be compared to Portland and its Columbia and Willamette River hinterlands. It can lead to a general discussion of why cities become economically wealthy when hinterlands often do not. And that can lead to broader questions about rural vs. urban conflicts, resentments, problems, which characterize Northwestern history and politics.

Brainerd's thorough work, tenacity, and sheer volume of effort paid off. According to its own sources, Seattle managed to draw 3/4 of the gold seekers to its stores and wharves. The actual number is difficult to pinpoint. The Seattle Trade Register reported 15,000 miners moving through Seattle from January through March, 1898, which was one of the most crowded periods. But that was only three months. The numbers must have reached three to four times that number in the next two years, but, given the transient nature of the population, it was difficult to tell. In January, the Trade Register reported that the jobbers, or supply houses, had stocked their premises almost beyond capacity. Several new outfitting establishments opened up in January 1898 as well. Grocers opened new businesses as well.

With thousands of men and women passing through Seattle on their way to the Klondike and Alaska, each of the city's and the region's industries received a boost. Seattle merchants sold meat, dried fruit, and flour to the miners, as well as clothing and equipment. They shipped lumber north to Skagway and Dyea to build new towns, boats, and docks. The Moran Bros. and other Seattle shipbuilders began construction of scores of new steamboats. On Whidbey Island, potato farmers and processors began to produce dried potatoes for the farmers, and sold tons of their traditional crop in novel ways. Ships that usually sailed north with tin for salmon canneries carried miners and equipment north as well, and returned with salmon.

The city's infrastructure received its share of benefits. With thousands of transient miners in the city, hotels and rooming houses were overbooked. The construction business boomed, with new houses and businesses, restaurants and hotels. Feeding and housing the miners created jobs, which drew more people, which created more jobs. The amount of money passing through Seattle banks went from $36 million in 1897 to $68 million in 1898 to over $100 million in 1899. The population, though always roughly estimated, may have reached over 60,000 by 1898, and would reach 80,000 or 90,000, give and take the transient population, by the turn of the century. The 1900 U.S. Census put it at 80,700, not counting Ballard and the suburbs.

Seattle was able to boost its economy when miners returned as well. Almost immediately upon learning of the gold strike, the Seattle Chamber of Commerce petitioned the federal government to establish an assay office in Seattle. The office was in place in the city by the summer of 1898. This meant that miners returning to Seattle could have their gold tested and given value right in the city, and that they could exchange that gold for coin or paper money. Before, they had had to travel to San Francisco to get an official government assay. With Seattle's assay office in place, gold, money, and spending power flowed straight into the city.

Where some money flowed, more money followed. Seattle's status rose in the eyes of major corporations around the country. Both railroads, the Northern Pacific and the Great Northern, invested millions in upgrading their Seattle waterfront facilities in order to handle the transshipment of goods from trains to ships and back again. Much of that transshipment expanded far beyond the Alaska trade to include expanding imports and exports to Honolulu, the newly conquered Philippines, and the Far East. With new wharves and docks, major steamship companies could establish headquarters in Seattle in order to serve the growing Northwestern trade network.

The Klondike gold rush was certainly a good example of a city taking advantage of a temporary boom. It was also more than that. Once Seattle had "captured" the Alaska trade, it moved beyond the temporary benefits to solidify the economic ties between the city and Alaska.

Seattle reached out and claimed Alaska as its hinterland, a large and distant source of raw materials, and a market for Seattle's commerce and production. It learned to funnel Alaskan people and resources into and out of Seattle, and used the wealth produced through this core-hinterland relation to re-make itself as a leading national metropolis. After 1900, the city saw new buildings, like the 1904 Alaska building, the city's first modern skyscraper. Engineers began plans for the Denny regrade, washing away hills to extend the city's commercial district. Planning began for the Lake Washington ship canal, to link inland freshwater lakes with Puget Sound. This urban and suburban development, combined with burgeoning trade connections, set the city on a new course in the 20th century. By 1905, the city directory labeled Seattle "The Metropolis of the North Pacific" and "The Gateway to Alaska and the Orient." In that year, the directory also stated that "the merchants of Seattle practically control the trade of Alaska, and the Yukon Territory, which is $20,000,000 per annum and is increasing yearly. . . . Seattle is the headquarters and base of supplies of the Puget Sound, Alaska, and Fraser River salmon fisheries, which produces salmon valued at $15,000,000 per year."

Of course, no one realized any of this more than the city's economic community. Once the initial effects of the Klondike boom waned, the Chamber of Commerce took action to solidify trade ties with Alaska, and to continue to promote the city's growth. The greatest expression of their efforts was the 1909 World's Fair, Seattle's Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition. The AYPE celebrated Seattle as the center of an international trade system linking the city and its northern hinterland, and the Asian-Hawaiian-Philippine trade connections as well. On the fairgrounds at the University of Washington, the buildings and exhibits celebrated the peoples and products of all of Seattle's trade hinterlands and trade partners, highlighting the city's economic and cultural achievements. The fair's exhibits and rhetoric made it clear that Seattle was really the most important Alaskan city, even though it was not even in Alaska. Seattle's business community was dedicated to economic development in Alaska, because development in Alaska meant wealth for Seattle. Seattle's attitudes combined a great pride and self-aggrandizement with gratitude. During the AYPE, the city placed a statue of William Seward in Volunteer Park in order to honor the man that had convinced the country to purchase Alaska in 1867. Seattleites knew that they owed much of their newfound prominence to Alaska, but still asserted their own greatness. This tended to annoy Alaskans, a resentment that continues, along with Seattle's ties to Alaska, to this day.

The document sources here provide source materials with which students can investigate Seattle's role in the gold rush, and uncover the ways in which Seattle harnessed this event to fuel its own growth. However, there was more to the gold rush than that. For the hundreds of men and women who left home in search of gold, it was a futile act, an incredible amount of hard work, and a great adventure. Very, very few of those men and women found much gold. Some broke even, some came back destitute. A small, small percentage struck it rich. Most who did had to invest a lot of money in order to do so. While stories abounded of poor men and women who in one day became millionaires, it happened only to a tiny handful of people.

For the majority, the experience of the gold rush was not about getting rich, but about hard work, struggle, and privation in a new environment. The documents here provide a number of comparative perspectives on this experience—men and women, workers and miners. They include diaries and journal entries from the trails and rivers that led to the goldfields, and from the mining towns and mines themselves.

Most miners who outfitted in Seattle took one of four routes to the Yukon goldfields. The "rich man's route" was by steamship all the way—from Seattle through Dutch Harbor and into the Bering Sea. During the few months free from ice, steamers could enter the mouth of the Yukon at St. Michael's and get up river to Dawson City. This was a long voyage, and expensive, but provided a relatively easy trip. The Stikine River-Teslin Trail was another less popular route, due not to expense but to difficulty. Miners took steamers up the Stikine River from Wrangell, Alaska, passing almost immediately into British Columbia. From the head of navigation at Telegraph Creek, they commenced a difficult overland journey with sleds and pack trains that proved for many nearly impossible. The trail led them to Teslin Lake, and thence to the other lakes that formed the headwaters of the Yukon. The letters of Hunter Fitzhugh, excerpted in the documents, describe the challenges of this route.

The majority of miners took either the Dyea Trail over Chilkoot Pass or the White Pass Trail over White Pass. These famous trails left from Dyea and Skagway, respectively, two small towns at the head of Lynn Canal. Skagway was the bigger town, booming quickly as the break-and-bulk point for people and supplies that came off of steamships and were taken up the trails. The White Pass Trail was the less grueling of the two trails, passable by horses and mules. It was plagued by unbelievable mud and rough terrain, which resulted in the death of scores of horses and other animals. The trail was replaced by the White Pass and Yukon Railroad by 1899.

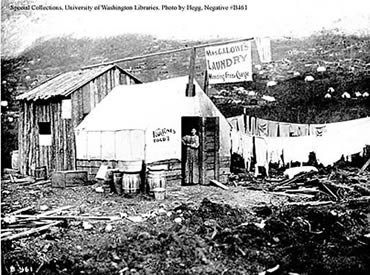

The Dyea Trail was the most famous, and the greatest physical challenge. Too steep for horses or mules past a certain point, miners had to haul their hundreds of pounds of supplies on their backs. They moved up and back on the trail, making multiple trips over each section, shuttling loads further and further up the trail. The greatest challenge came in the final ascent of the pass, which was as steep as a staircase, though this staircase was carved in snowpack. The ascent to the summit, and then the descent to Lake Lindeman, were for many the most grueling experience of their lives. Scores of miners gave up while attempting these trails. They sold their outfits to others and headed back down to tidewater to find passage south to Seattle or other cities. The trails became moving marketplaces, dotted with buyers and sellers, crude lodging establishments and restaurants. The miners proved a lucrative captive market for those who could find something to sell—and there always seemed to be something to sell.

Most miners crossed the passes in late winter, February or March, and then camped along the headwater lakes, Lindeman and Bennett, until the ice cleared from the lakes and rivers in April and May. They built boats at the lakes, buying lumber from sawmills that appeared out of nowhere, or whipsawing their own lumber. This was particularly hated work, one man positioned beneath a log, one above, while the log sat on a high frame. The two men than push-pulled a cross-cut saw up and down through the log—the man on the bottom subject to falling debris, the one on top to losing his balance. Many friendships and partnerships foundered on this work.

In the spring, miners launched their heavily loaded barges, rafts, scows, and even small steamers, and headed down the long lakes to meet the Lewes River, which joined with others to become the Yukon. There were several challenges along the way, including the White Horse Rapids and Five Fingers Rapids, which wrecked quite a few boats and even killed people. Once they passed these points, most miners turned to the task of finding gold-bearing claims to mine. Some, hearing that the Klondike fields had been completely claimed, headed up other rivers in British Columbia, like the Stewart, to prospect for new gold-bearing ground. Some headed past the Klondike and Dawson, across the border to Alaska, where they prospected a series of American creeks, including Independence, Fourth of July, the Koyukuk River, and Manook Creek (also spelled Mynook, and Munook) near Rampart City, Alaska.

In 1899, news of a strike near the mouth of the Yukon led many miners to leave the fields of the upper Yukon for Nome, which became the site of a second large-scale gold rush. Hundreds took steamers north from Seattle in 1900 to mine the beaches and creeks at Nome. They joined the crowds from the Yukon in taking brief stabs at finding gold, but few lasted longer than a few months in Nome. Because Nome was on the coast, with direct access by steamship during the ice-free season, Nome was built almost instantly. Anything that could fit in a ship was brought from Seattle, from whole buildings to narrow-gauge railway tracks. Despite the ability to get almost anything to Nome, the miners still had to grapple with the environment and the complete lack of wood.

Hundreds of miners did go to the Klondike goldfields in Yukon Territory, and to Dawson City, the town that grew up at the mouth of the Klondike where it flowed into the Yukon. Few of these miners could get claims on the rich creeks of the Klondike district, but many worked for wages for other mine owners, or worked others' claims on a share system, which was called a lay claim. Some were able to break even doing this kind of work. Others made enough money to attempt to prospect other creeks on their own. Most made little progress, or turned to other jobs and other ways of making money. Huge numbers, hundreds, realized that without claims on the rich creeks they had no hope of becoming millionaires. They immediately got on steamers and headed down the Yukon for home before the rivers closed up for the winter. In the early winters, 1897-98, for instance, many attempted to leave during the winter, by dogsled. This was a grueling and dangerous trip as well.

For those who stayed, the work of gold mining provided its own set of hardships and challenges. The work was profoundly affected by seasons and the sub-Arctic climate. In order to find gold-bearing gravel, miners had to sink shafts next to existing creeks down to older stream beds that had been covered up with 10-20 feet of muck, dirt, and permafrost. Running water posed a challenge, so miners dug in the winter, when the creeks were frozen. They used fires and hot rocks to thaw through the permafrost and loosen the dirt. Digging and thawing, they excavated deep shafts, piling up the dirt and gravel on the surface, to wait for spring. Only in spring, when the ice cleared, could they get the running water needed to wash, or sluice, the "pay dirt" and separate out the gold. Miners panned samples of dirt all winter to test their claims and assess the amount of gold in any particular hole or drift, but they never knew how much gold they were going to get until the spring "wash up" when they sluiced the gold or used rockers to separate it out. This meant that miners could do back-breaking labor all winter, and end up with very little money at the end. Faced with such disappointment and uncertainty, many miners gave up quickly and headed home. Others found wage labor jobs, cutting wood or digging for other miners. The profitability of individual placer mining declined quickly after the first few seasons. Individual miners and small groups of partners could unearth the easily accessible nuggets. Mining for finer gold required much more massive and expensive equipment, especially dredges. After 1900, large companies began buying up claims along the Klondike and at Nome, and the creeks soon became the site of large scale technological mining. As a popular field for individual miners, Alaska and the Klondike faded rapidly.