Engaging Your Employees

Lynn D. Hagerman, MPH, CHIC; Lynn Hagerman Associates, LLC

Leaders intuitively know that when teams and employees are fully engaged, things seem to flow more smoothly, the work feels lighter, and outcomes are better. Employee engagement can make the difference between a ho-hum environment with good-enough results and a working environment that truly excels.

Why Engagement is Essential

As leaders, we want a high level of engagement at all times but it becomes truly essential at times of change. When employees are genuinely involved in creating or contributing to new initiatives, they become more committed to positive outcomes and finding ways to meet stretch goals. They're more creative and invested in problem-solving. They're also more successful, and then, so is the organization.

A trusted resource on this topic is Richard Axelrod, author of Terms of Engagement: New Ways of Leading and Changing Organizations. While Dick Axelrod is an organizational consultant, he also has "walked the walk" as a senior leader, and his concepts evolved from testing in real-life leadership situations. In his work, Axelrod points to research findings that demonstrate the importance of employee engagement, including a 2010 global study of successful organizational transformations that identified employee engagement, co-creation, and collaboration as a key success indicator (McKinsey & Company 2010).

I have also experienced the difference in results when employees are engaged, through leading strategic planning, service development, implementation, and expansion efforts in a variety organizational settings.

One large initiative in particular stands out from when I served as Vice President for Safety and Health for GTE (now Verizon) in the 1990s. GTE was one of the first large companies in the U.S. to move to a smoke-free workplace. While it might be hard to imagine now, at the time this required a substantial cultural shift. We had 6,000 employees in facilities of varying size across five northwestern states, but we were able to make this change relatively painlessly and in a positive fashion through using community organizing principles—principles that closely resemble the keys to employee engagement that Dick Axelrod espouses.

Designing Work that Enhances Engagement

According to Axelrod, "Engaged employees put their wholehearted selves behind what needs to be done." Who wouldn't want to be in a workplace where that is happening most of the time?

Axelrod provides a few simple guidelines for how leaders can design work with an engagement edge:

- Find meaning.

- Put autonomy in charge.

- Construct scorecards.

- Create challenges.

Meaning. We all become more motivated and put more of ourselves into activities when it feels meaningful. The work itself may be intrinsically meaningful, as in being a doctor or teacher. Or, if it is ancillary to the delivery of a service, "meaning" can be found in one's own sense of purpose, in doing a job well, or seeing how it helps with the delivery of an overall effort. For example, custodians may help the University run smoother because they seek to provide a better physical environment or because they feel a part of an overall team that delivers on behalf of the students. (A case in point at the UW is custodian and 2010 Distinguished Staff Award recipient Ui-Hak Chong.)

Identifying the sense of common purpose is an essential leadership task. Leaders can reinforce meaning and renew purpose through meetings and conversations that reinforce the "why" of what the team or organization is doing.

Autonomy. To the extent that decisions can be made closest to the customer or to others affected, the better. Nordstrom is famous for the latitude it allows its sales staff to make decisions to please the customer. At what point in your organization—how many flights up—may the employees make decisions that affect their own work and/or the delivery of the service they are responsible for?

Leaders can consider how this distance—or lack thereof—might affect each employee's sense of autonomy and, as a consequence, level of engagement.

At GTE, we were unwavering in our goal to become smoke-free within 18 months, but we let each facility determine how to accomplish this. We genuinely involved employees by identifying informal and formal leaders at each facility and keeping control at the closest level to those affected. While implementation strategies varied widely from facility to facility, the goal was achieved by the target date. Since employees had determined how to implement the change at their own facility, they were engaged in the entire process and then had ownership in the initiative's success.

Scorecards. Leaders who have been involved with UW's Organizational Effectiveness Initiative have probably developed a respect for the usefulness of performance measures. Scorecards and other tools that focus on reporting individual, group, and organizational metrics in a timely manner provide feedback that allows for a shared sense of accomplishment, as well as for nimble turnarounds and course corrections.

Constructing measures is related somewhat to autonomy. Leaders should consider how easy (or hard) it is for employees to access feedback and to know how they're doing.

Challenges. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi has studied and written a great deal on the concept of "flow" (a mental state in which peak performance is attained). One of his most useful concepts relates to the interaction of skill and challenge, and its effect on boredom and anxiety. People, in any endeavor, need a good match between their skills and the amount of challenge involved.

To enhance employee engagement, leaders may consider how well an employee's skills are matched to any particular challenge. If there is insufficient challenge, people get bored; too much challenge, then anxiety sets in and people shut down and lose their ability to be creative.

Leadership Practices that Build Engagement

Axelrod proposes the following best practices for how leaders can engage with employees and promote engagement in their organization.

No "Burning Platform." It can be tempting to create a sense of urgency through naming an issue as "burning" in its importance and potential impact, but in Terms of Engagement, Axelrod cautions against this. People may already be in a fear mode or may have higher anxiety in environments of rapid change. Using the burning platform can heighten the anxiety and rings as untrue when there's one new burning issue after another. This leads to people tuning out the issue and its urgency, and a kind of organizational "fatigue."

Straight Talk. It's important to share facts without distorting or exaggerating them. Although it can be uncomfortable at times, leaders must be honest and straightforward and must simply tell the truth.

In our smoke-free initiative at GTE, our straight talk was communicating to our employees that the company leadership believed the emerging data: second-hand smoke was a serious health risk. We were also clear that, as a consequence of this belief, creating or maintaining designated smoking areas inside our facilities was not an option, especially when ventilation systems in facilities simply re-circulated the air.

Transparency. Leaders should strive to be transparent about the facts of any situation and about how they're feeling about the situation, including any doubts or concerns. Being transparent as a leader can lead to being viewed as more human and open a path for employees to be more forthcoming about what is true for them.

At GTE, we were clear about why we were making the change to a smoke-free workplace and that protecting the health of all employees was our number one value. We were also clear about what wasn't negotiable (becoming a smoke-free workplace within 18 months) and what was negotiable (almost anything about how each facility went about becoming smoke-free).

Building Trust. Rapid and repeat change—such as has been experienced at the UW over the past few years—can create uncertainty and thereby take a toll on levels of trust. Finding a way to create an environment of higher trust, even in the midst of change, is an essential leadership pursuit and enhances employee engagement. Leaders may reflect on their own skills and personal style, and consider how their style enhances, or detracts from, trust-building.

Engaging Through Trust

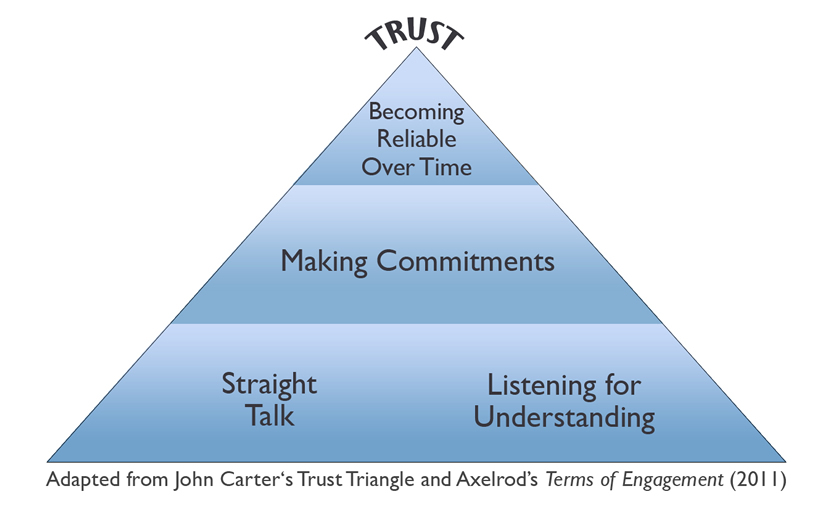

How leaders engage with their employees is crucial for establishing and maintaining trust. Axelrod references a "Trust Triangle" developed by John Carter of the Gestalt Institute. Several components form and strengthen this triangle:

- Straight talk and honesty, as mentioned above.

- Listening for understanding. Asking questions, more than telling, allows you as a leader to learn what is on people’s minds and to see what people have heard from what you’ve said. (Active listening is a great model to follow for this part of the triangle.)

- Making commitments and keeping one’s word. You may not be in a position to make commitments on behalf of the whole organization, but you can make commitments related to how you will lead your own department or team. Don’t be afraid to refer back to commitments that you weren’t able to keep. (Revising agreements is okay—that is part of trust building.)

- Becoming reliable over time. When employees learn what they can expect from you, this builds in some certainty when our world and working environments are uncertain.

Building trust is an ongoing pursuit and something that leaders accomplish over time. If your employees become certain that you will engage them honestly, be transparent about organizational/departmental issues, include them in the solutions, and expect them to be heard, trust will be enhanced and so will their level of engagement.

Lynn Hagerman, an experienced consultant and leadership coach, is a member of the University Consulting Alliance. You can reach Lynn through the Alliance at alliance@uw.edu.

========

SOURCES

Dick Axelrod, “Employee Engagement and the Organization Development Practitioner,” Practicing Social Change, Issue Three, April 2011

Richard H. Axelrod, Terms of Engagement: New Ways of Leading and Changing Organizations, Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc., 2010

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, Good Business: Leadership, Flow and the Making of Meaning, Penguin Books, 2003