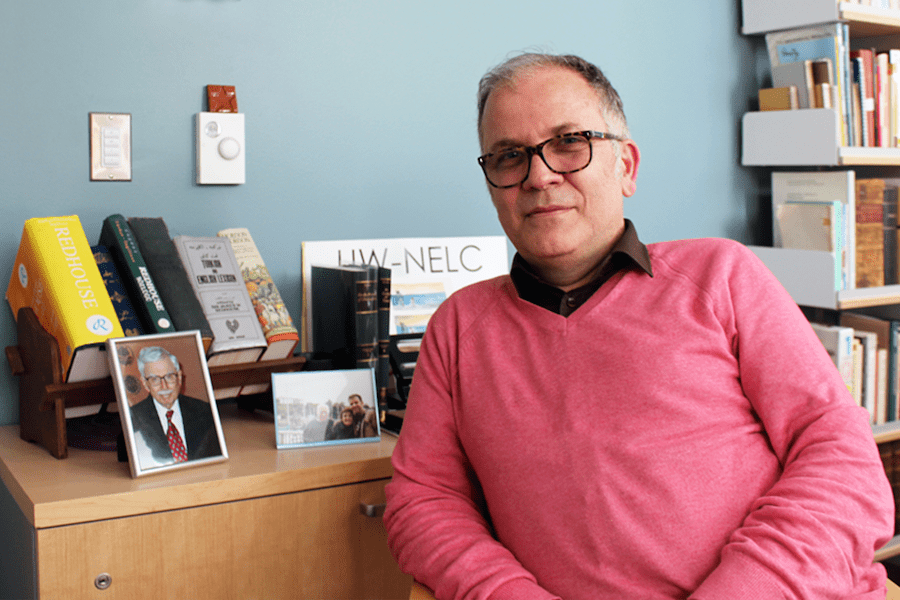

Faculty Friday: Selim Kuru

Selim Kuru’s love of literature all started with his mother, Nihal.

“She was an avid reader and had a library under lock and key and would release books for me according to my age,” Kuru recalls of his youth growing up in Samsun, a city on Turkey’s Black Sea coast. For Kuru, “reading turned into a game”—a recurring quest to unlock that next book from the library shelf in search of what hidden knowledge it might contain.

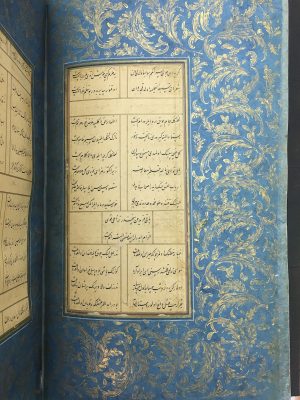

With time, Kuru became fascinated with the literary puzzles presented by the literature of Turkey’s Ottoman imperial past—centuries old poems and other intricate and artful manuscript texts rendered widely inscrutable when the Turkish language reform of 1928 introduced a new Turkish writing system based on Latin letters, ending a more than 600-year history of writing the Ottoman Turkish language in an adapted form of cursive Arabic script.

“As a Turk, you feel like you know Turkish, but then going to this Ottoman high literary language, it’s a bit like going [from modern English] to Elizabethan palace-produced texts,” Kuru says, drawing a comparison between the ornate shorthand writing often used for official court correspondence in England during the 16th and early 17th centuries and Ottoman texts from roughly the same period. “You may not immediately get the meaning.”

Turkey’s language reform of 1928 was just one in a string of what Kuru calls “truly singular events” that constituted the nation’s break from its imperial past to become a rapidly modernizing republic in the 1920s.

For Turkish scholars, however, the modern-minded reform meant the nascent republic was in danger of losing touch with centuries of literary, historical, and cultural tradition bound up in the old Ottoman manuscripts. The nation’s textual heritage, it seemed, was also in need of a modern makeover.

Thus, scholars began the Herculean labor of transcribing vast troves of precious texts and documents written in the Arabic/Ottoman script into Latin letter alphabet versions. Some 90 years on, the work is still ongoing with transcription of Ottoman script to modern Turkish constituting a core of scholarly work done on Ottoman literary, historical, and cultural texts to this day.

The pressing nature of the cultural preservation project meant that the process of creating Latin letter editions from large, widely dispersed groups of manuscript copies was often done hastily—most often skipping essential steps such as creating foundational editions in the Arabic script and examining representative samples of manuscript copies of a text.

Mahmud Abdülbâkî (1526-1600) wrote poetry under the pen name Bāḳī (the Enduring) during the reigns of four Ottoman sultans. Acclaimed “Sultan of Poets” during the so-called “Golden Age” of Ottoman literature, Baki was a regular guest at the salons and private entertainments of Sultan Suleyman the Magnificent (r. 1520-1566) and a noted scholar and jurist.

As a result, significant features of the original texts were lost, such as the spelling in Arabic script of Turkish words and significant rhetorical embellishments reliant on the visual characteristics of the Arabic script.

However, this 20th century-created problem, may be on the verge of a 21st century solution in the form of The Bāḳī Project, a UW-based international collaboration initiated and run by Professor Walter Andrews, who founded the Turkish and Ottoman Studies Program at UW. The project aims to establish a full digital representation of all the traces of the 16th century poet Bāḳī, widely considered one of the greatest contributors to Turkish literature.

“There is a lot of thinking and imagination behind his poetry,” Kuru says. “Bāḳī’s poems have a really lofty sense; they are like intricate jewels: very finely worked.”

The son of a preacher in a Sultanic mosque, Bāḳī came to be accepted as the leading poet of the Ottoman Empire—known widely as Sultânüş-şuarâ (سلطان الشعرا), or “Sultan of poets.” His development of a lofty style full of wordplay and veiled meanings earned him positions as a statesman, scholar, and friend of Ottoman sultan Suleyman the Magnificent.

“These [Ottoman] systems value poetry and its function of creating imagery, honing your linguistic skills, and learning cultural information as well,” says Kuru, who chairs the University of Washington’s Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations while also serving as associate professor, director of UW’s Turkish and Ottoman Studies Program, and The Bāḳī Project’s principal investigator. “Poetry is a part of learning.”

Today, Bāḳī’s poetic oeuvre exists as a fragmented array of some 180-odd manuscript copies known in Turkish as divan—each with its own unique differences based on age of creation.

At his death in 1600, Bāḳī’s divan encompassed some 650 or more poems ranging from panegyrics and occasional verses to love poems, fragments, and poems in Persian. Kuru says The Bāḳī Project seeks to make sense of and bring order to these remnants of the poet’s legacy. Currently, an international team split between the US and Turkey transcribes handwritten poetical selections from three divan copies from Bāḳī’s lifetime.

For more than 600 years, the Ottoman Turkish language was written in an adapted form of the cursive Arabic script. The language reform of 1928 introduced a new Turkish writing system based on Latin letters.

“Now, many people in Turkey and other states are entering different copies of the text and we are trying to develop a system to compare them along with giving each object/manuscript full representation,” Kuru says. “By comparing different poetical texts, we can chart a poet’s political development—as well as the poet’s own development.”

Kuru hopes the project will help scholars to discover things not previously known about the production of Bāḳī’s manuscript books—allowing researchers to test all copies against each other to detect variants and textual lineage as well as what might have been lost during the transmission of the documents.

However, winnowing out a more complete sense of Bāḳī’s own poetical process and personal development is hardly the end-goal for the project, Kuru says. In reality, Bāḳī serves as a convenient means to an undetermined end.

“This project is very important, not only because we have really excellent editions of Bāḳī’s poems, but meanwhile, we are developing tools such as transcription and compilation tools and how to set up an archive,” Kuru says. “It’s all about analytical thinking.”

With the advent of digital technologies and tools, it has become possible for researchers to accomplish transcription and editing tasks that would have been prohibitively time-consuming and expensive only a few decades ago.

One such tool is Scribe, a digital transcription tool created by researchers from the University of Washington Informatics School, aided by Turkish transcription experts and Ottomanist scholars. The Scribe tool creates a digital text, which eliminates the gap between the Arabic script in the original and the Latin letter transcription by associating every Latin letter directly with an Arabic script equivalent.

The result is a Latin letter transcription that produces, from the same source, a digital transcription in the Arabic script. This means that no gap exists between the Latin letter and Arabic script transcriptions and that any Latin letter input must produce Arabic script output that is directly comparable to the original text.

Kuru says it helped that Bāḳī only worked on small-form poems, making textual data easier to process.

“In the process, our students are learning things we wouldn’t even imagine,” he says. “Being there, working with us, without an interest in Bāḳī, necessarily, they’re learning other things and skills. Bāḳī is our anchor.”

That’s why Kuru continually stresses that the project is as much or more about process than any specific end goal.

“There’s a lot of promise in the digital humanities,” Kuru says. “You constantly have to discuss with different people for different steps, so it creates this intellectual community in a sense where everyone speaks a different language, but it adds up and comes together.”

So far, The Bāḳī Project has brought together experts from Engineering, Informatics, and Humanities. From his perspective as a scholar of Ottoman poetry and literature, Kuru says he would like to come to an understanding of what made Bāḳī so enduringly popular.

“It’s like asking why Shakespeare was the best English author of all time,” he says. “Nobody can explain it exactly; there are so many factors.”

Ultimately, Kuru says, the project will be cause for Bāḳī to “gain more space in the canon of Ottoman literature, because no other poet is being studied in this manner.” The project’s ongoing, open-ended, multi-disciplinary elements are at the core of the work Kuru hopes to continue at the University of Washington, especially when limited numbers of scholars of Ottoman studies so often demand a collaborationist approach.

To that end, each summer since 1997, Kuru has traveled to the island of Cunda off the Turkish coast to instruct graduate students from different American universities as part of a six-week program on Ottoman paleography, the study of ancient writing systems and the deciphering and dating of historical manuscripts. In 22 years, the program has graduated some 500 students.

But each fall, Kuru is pleased to return to Seattle—his home since earning his PhD from Harvard in 2000. He says the weather—“rain and gloom in winter, but nice summers”—reminds him of the Black Sea coast.

“Coming to Seattle was kind of like coming back home.”

Selim Kuru holds an M.A. from Boğaziçi University, Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü, İstanbul, Turkey and a Ph.D. in Near Eastern Languages and Cultures from Harvard University.