Bumping Against the Glass Ceiling

It's too bad Colwell didn't think to get a helmet then because she would bump her head on that glass ceiling many times in the next few years. She earned a full scholarship to Purdue University, and got a bachelor's degree with distinction in bacteriology. Her goal was medical school, but first she set her sights on a fellowship to earn a master's degree in bacteriology. Her department chairman denied her a fellowship because they "were not wasted on women." By then, she had met a handsome fellow grad student named Jack Colwell, and they were soon married. Colwell ended up switching subjects to genetics, got her master's degree, and she and her new husband were off to the University of Washington to pursue Ph.D. degrees—Jack in physical chemistry and she in microbiology.

Colwell and her husband, Jack, enjoy the sun on the balcony of their home in the Showboat Apartments while both were doctoral students at the UW in 1958. Photo courtesy Rita Colwell.

"One of my fondest memories," Colwell recalls, "was when Jack and I arrived from the Midwest. Our car was packed with books, clothes, records, everything we owned. We were so excited to come to Seattle, and we drove to Parrington Hall. This was before there was a 'Red Square,' and it was sunset. The sky was clear and Mount Rainier was so fabulously pink. This was our introduction to the UW. It was amazing."

Despite the fact that she and Jack loved Seattle—especially racing dinghies on Lake Union and spring skiing—her first experiences at the UW were not so uplifting. Her first adviser, a prominent geneticist, gave her "no support," although he seemed to find time to work with male graduate students. Eventually she found an adviser who would have a profound impact on her life—Microbiology Professor John Liston.

Not your run-of-the-mill, old-school professor who treated graduate students like cheap labor, Liston gave his graduate students lots of rein. He trusted Colwell to outfit his new lab, order equipment, work with the carpenter, and set things up. He also expanded his students' horizons, insisting they read authors such as James Thurber and Aldous Huxley and read about every subject under the sun—history, science fiction, humor, political science—in addition to their very serious work in the lab.

"Ricky was a self-starter from day one," Liston recalls. "She needed very little supervision." He recalls how she helped him build the scientific apparatus they needed for a course on aquatic microbiology, and how she would spend nights working in the basement of Bagley Hall on huge computers, writing codes and doing highly detailed statistical analysis of her research.

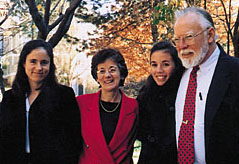

On the morning of her swearing in as director of the National Science Foundation, Colwell enjoys a moment with her family in front of her home in Bethesda, Md. From left are daughter Alison, Colwell, daughter Stacie and husband Jack. Photo courtesy Rita Colwell.

Colwell—who received her $170 monthly stipend at the UW from a $36,000 National Science Foundation grant—went on to become the first woman to earn a Ph.D. from the UW College of Oceanography. She also developed a reputation for trying innovative approaches and tackling unpopular theories—something that would serve her immensely well later in her career.

After earning her Ph.D. in 1961, she stayed on as a research professor at the UW until 1964, when her husband got a fellowship to join Canada's National Research Council in Ottawa. Colwell was offered a postgraduate position of her own at the same agency, but at the last moment, the agency decided that its anti-nepotism rule prohibited it from offering fellowships to husbands and wives simultaneously.

So Liston came to the rescue, getting more NSF money to fund a position for her on the UW faculty, and then finagling a visiting professorship at the very Canadian agency that reneged on its offer to her. It was a lesson in ingenuity and loyalty that would leave an indelible impression with her.

"She is a very loyal person to everyone she meets," says Bill Wiebe, '65, a classmate of Colwell's at the UW and now a professor at the University of Georgia. "She also remembers everyone and has a knack for getting people from different parts of the country together to work on great projects and ideas."

After her two years in Canada, she joined the faculty of Georgetown University (she was that institution's first woman faculty member in science), where she lasted until 1972, when the University of Maryland came calling.

By then, she had established herself as a major player in science. In the 1960s, she was the first researcher in the U.S. to develop a computer program to analyze bacteriological data.

Go To: Page 1 | Page 2 | Page 3 | Page 4

- Return to June 2000 Table of Contents