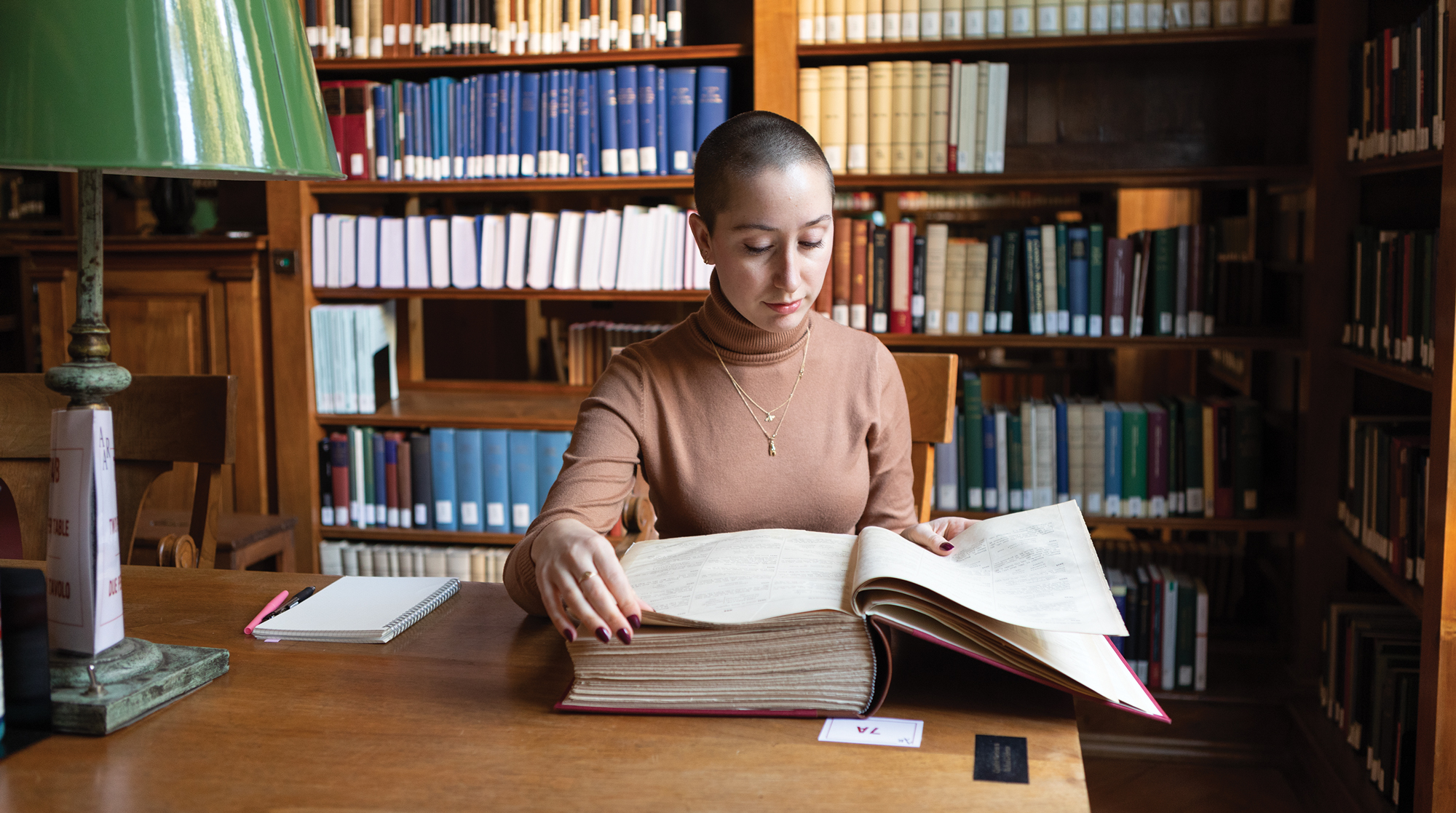

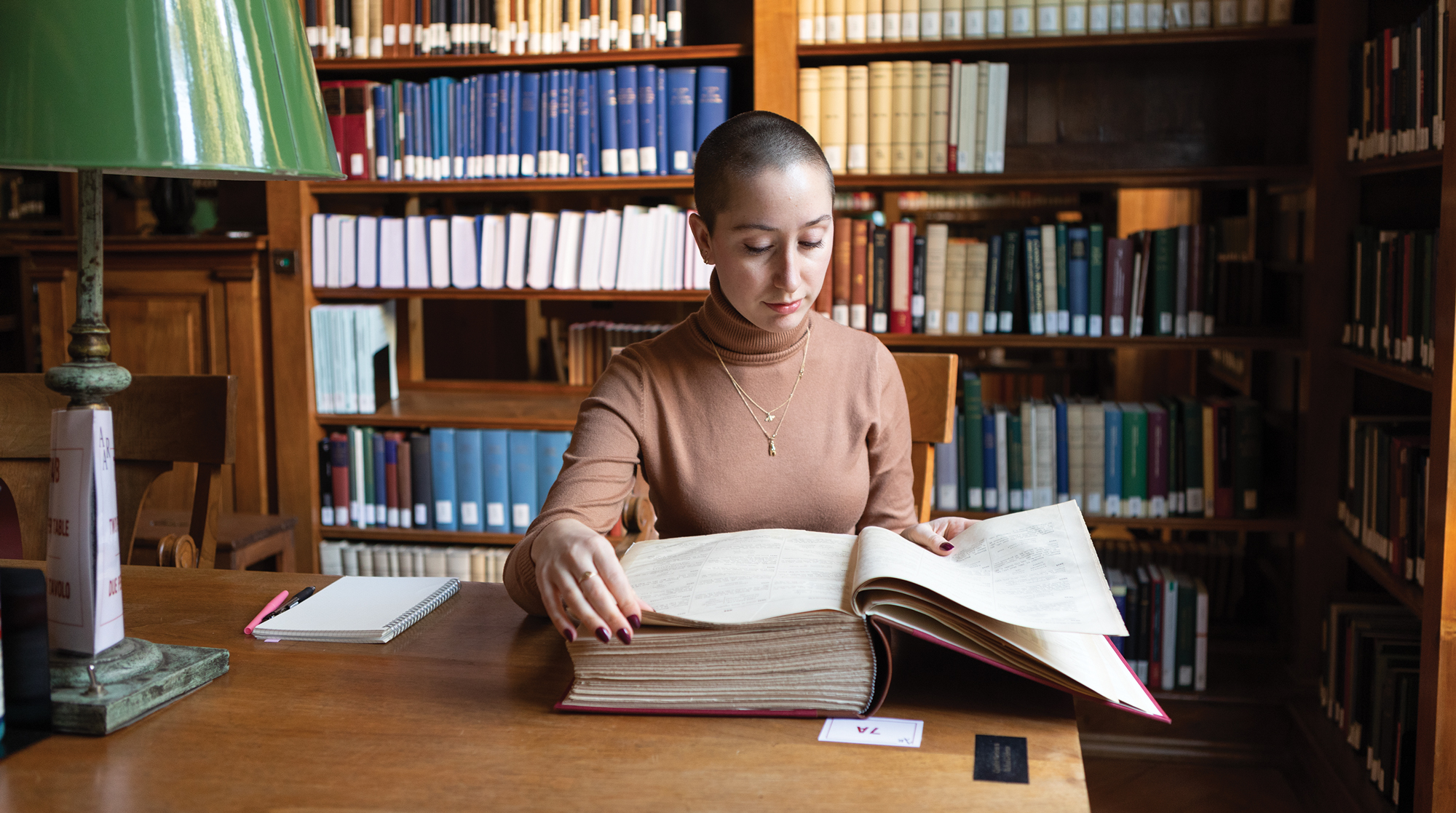

While most doctoral candidates spend their last year of school teaching and writing, Grace Funsten, ’17, ’22, spent hers in Rome visiting cool, underground chambers where the ashes of certain ancient Romans were housed.

A winner of the coveted Rome Prize, Funsten joined a group of select scholars in the Eternal City this year and pursued her studies from a home base at the American Academy. With a stipend and command of Latin, she steeped herself in funerary verse carved in marble. The epitaphs often recounted illicit love affairs, but Funsten saw a deeper context: These were indicators of larger political change and featured the voices of the non-elite, words that would otherwise be lost to posterity.

Funsten’s pathway to Rome started with a Latin class in high school. Studying classics at the UW, she became hooked on epigraphy, the study of ancient inscriptions, in a graduate seminar taught by Sarah Levin-Richardson. She was delighted by an epitaph for a dog called Margarita. It was written around the second century A.D., and in the dog’s own voice. She found the message was not so much an expression of grief as a parody of elegy. It even referenced the work of the poet Ovid, she notes. Funsten’s paper on the poem brought her her first recognition in the field.

Another poem Funsten studied this year was found in a large cemetery, called a columbarium, discovered off the Via Appia in 1852. Underground and several stories deep, this burial chamber was the resting site for the ashes of freed men and enslaved people, as well as traders and tax collectors. The engraving is difficult to access because it’s on private property, says Funsten, but there are photographs to work from. The words seem to tell the story of a woman who had multiple love interests. In Funsten’s reading, the poem suggests that the woman attracted attention with the jewelry her lover gave her and that an envious person killed her.

Funsten’s scholarship covers fresh territory. Its unique focus is verse epitaphs found in columbaria. “That’s exciting, because we don’t have poetry at all from enslaved or formerly enslaved people, or much writing from people of that time who weren’t professional writers,” she says. The epitaphs, which can offer a view into moments of great change, capture what is important to this non-elite group of people. “We’ve lost about 90% of the history from ancient Greece and Rome,” she says. “Here are otherwise untold stories.”