Undaunted Undaunted Racism, hate were no match for humanitarian

Racism and hate were no match for humanitarian Harry Kawabe, who built a legacy of giving that still echoes today.

Racism and hate were no match for humanitarian Harry Kawabe, who built a legacy of giving that still echoes today.

Harry Sotaro Kawabe is a great example of a UW graduate who, despite facing systemic racism throughout his lifetime, built the economies of two cities in his adopted homeland of America and created a legacy of philanthropy that still touches thousands of people today, more than 50 years after his death.

As a young man, Harry Kawabe left Seattle to join the gold rush in Alaska.

Born in 1890 in a small farming village near Osaka, Japan, Kawabe came to Seattle in 1905 and found work as a houseboy. But the America he arrived in was not friendly to Asians. The same year he arrived in Seattle, the U.S. Attorney General ordered federal courts to stop issuing naturalization papers to Japanese individuals. This was only a few years before California passed the Alien Land Act, which prohibited Asians from owning land. (Washington passed such an act in 1921.) After learning English during his time in Seattle, Kawabe left for Alaska in 1909 to work as a cook and try his hand getting rich mining for gold.

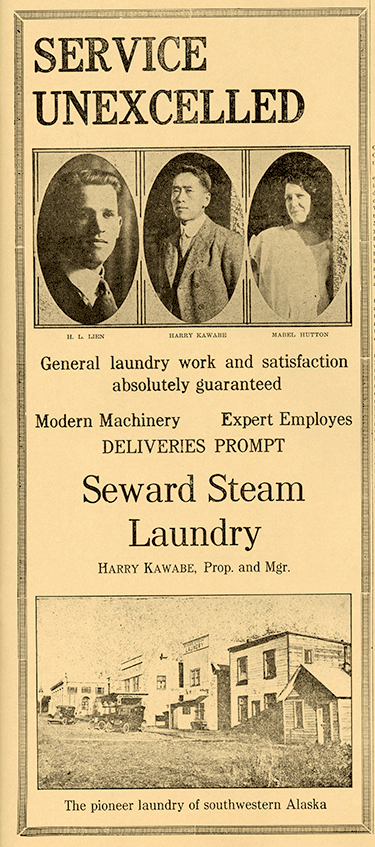

When that didn’t work out, he moved to the small town of Seward. There, his business instincts kicked in. He bought up empty lots and small businesses, in the process establishing himself as a prominent businessman and respected local citizen. He built a laundry business that served steamship and railroad lines. Investing in a gold mining operation near Alaska’s Moose Pass—halfway between Anchorage and Seward—Kawabe later ran several businesses in town, including a gift store, fur shop, bar and liquor store, hotel, barbershop, and several real estate holdings.

Kawabe built a laundry business that served steamship and railroad lines. (Historical images courtesy of the U.S. National Park Service)

He was living in Seward when Pearl Harbor was attacked on Dec. 7, 1941. Three months later, Kawabe was among the 120,000 American residents of Japanese descent—including 70,000 American citizens—who were forcibly relocated to detention camps in the American interior. Sent first to Alaska’s Fort Richardson, Kawabe was later incarcerated at Crystal City, near the Texas-Mexico border.

After World War II, Kawabe realized the deep financial losses he suffered during his incarceration. He returned briefly to Alaska, then moved to Seattle so he could pursue a business degree at the University of Washington. But he was no ordinary student, having already run businesses for decades in Seward and Seattle.

This time in Seattle was a heady period in Emerald City history. The Alaskan Way Viaduct was under construction near mom-and-pop laundries, jewelry and appliance shops, ice cream stands, as well as an earlier version of Uwajimaya and other groceries. (Many of those mid-century Seattle images appear in the works by photographer Elmer Ogawa, ’28, who told stories of the local Asian American community for several publications, including Northwest Times and Pacific Citizen. They can be found in University of Washington Libraries Special Collections.)

Shortly after his UW graduation, Kawabe became a naturalized citizen after the McCarran-Walter Act eliminated race as a basis for naturalization in June 1952. He and his wife, Tomo, lived in a brick house near 24th and Aloha, recalls Tomio Moriguchi, ’61, who sometimes drove Mrs. Kawabe and her groceries home from Uwajimaya on rainy days.

Kawabe Memorial House in Seattle’s Central District provides affordable housing to seniors.

Recovering from the financial losses during the war, Kawabe later made investments and grew his business assets in the Pacific Northwest. He was one of the first businessmen to envision exporting Alaskan natural resources to Japan. Shortly before his death in 1969 at the age of 79, he founded the Kawabe Memorial House in Seattle’s Central District to provide affordable housing for seniors, especially elderly Japanese Americans. The 154-unit complex was built through the HUD Senior Housing program in 1972. His last will and testament created the Kawabe Memorial Fund, which has funded more than 1,300 grant requests since 1971. In addition to human services organizations, the Kawabe Memorial Fund underwrites college scholarships to students from Seward High School, capital improvement projects for churches, and scholarships to train teachers, priests, and ministers. The funding committee meets three times a year to consider grant proposals.

This far-reaching philanthropy “reminds us that Kawabe always believed that entire communities—not just individuals—are capable of great things,” National Park Service historian Katherine Ringsmuth says on the Kenai Fjords website. The terrible treatment inflicted on this ambitious humanitarian didn’t discourage him from providing great resources to humankind and being an excellent example for us all.

Kawabe with cultural figures at the Kawabe Art Gallery in 1958. (Elmer Ogawa / Elmer Ogawa Collection, UW Libraries)

Pictured at top: Kawabe in 1967 (Elmer Ogawa / Elmer Ogawa Collection, UW Libraries)