November 1, 2007

Project seeks reasons for loss of women in biological sciences

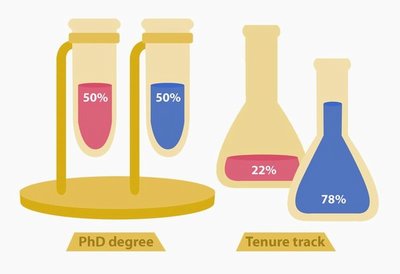

Compared to men there’s a higher percentage of women earning doctorates in biology than in most other fields of science. Recently, for example, the numbers have been nearly 50-50 some years.

But even before women get onto the bio-sciences tenure track, they start to disappear.

In the top 50 biological science departments nationally — in terms of funding — women made up 22 percent of tenure track faculty in 2005. That’s 35 percent of assistant professors, 27 percent of associate professors and 16 percent of full professors.

Where’s the nearly 50-50 going?

“In biology we have women to lose — we call it the leaky pipeline,” said Claire Horner-Devine, a UW assistant professor of aquatic and fishery sciences.

A joint UW and University of California Santa Cruz project with National Science Foundation funding is trying to find out the reasons for that leaky pipeline, and, just last month, offered what organizers hope will be an annual symposium for junior and senior women scientists in biology to learn from each others’ experiences.

The symposium Oct. 14-17 at the UW’s Pack Forest conference center involved eight assistant professors and 22 other women with doctorates who are pursuing tenure track positions. They came together with 18 senior women faculty as speakers. Twenty seven institutions were represented.

Participants were surveyed before the meeting and surveys will be conducted in six months and 18 months to shed light on what’s happening, says Horner-Devine, principal investigator for the WEBS project, which stands for Women Evolving Biological Sciences.

From presenters at the symposium, one key issue appears to be that women and other minorities encounter what Horner-Devine described as “little pieces of implicit bias all along the way.”

She and co-PIs Joyce Yen of the UW Advance Center for Institutional Change and Samantha Forde of UC Santa Cruz point to psychological research that, for example, shows that research papers with female authors attached to them scored lower with reviewers compared to identical papers with male authors.

Those attending the symposium said another implicit bias is that women appear to be asked more often to do outreach, without pay. That’s not necessarily bad or good, but on top of all the other obligations of being on the tenure track, it might be enough to break the camel’s back, says Horner-Devine.

For others the career track gets derailed when one falls in love with a fellow holder of a doctorate and the couple then faces the challenge of duel careers in academia. When the married women speakers at the symposium got talking, for example, they discovered that almost all had married fellow biologists, says Yen. As program and research manager for the UW’s Advance Center for Institutional Change, Yen tries to help people overcome such hurdles. Horner-Devine says the UW was a help when she and her husband — who holds a doctorate but is an environmental engineer rather than a biologist — decided to come to the UW.

“Women biologists often feel isolated in their careers and don’t know where to get the information they need,” says Forde. “They need to be equipped with strategies to successfully navigate the critical transition from graduate school to the tenure track.”

One perspective emerging from the symposium is that there are a lot of ways to make that happen, Horner-Devine says. It doesn’t all have to be the traditional path at a research university shortly after earning one’s doctorate. Alternative paths might be working for a non-research university, splitting a tenure-track position with another person or working on soft money and not pursuing tenure — the speaker doing this said she felt as if she actually had more freedom to explore the topics she was most interested in.

Horner-Devine is early in her career, having been at the UW three years — two as research faculty and now as an assistant professor. She came up with the idea behind WEBS after talking with peers and friends and realizing there was a need for women biologists to have a place to turn for support and ideas when making career decisions — both big and small.

Junior scientists from the UW taking part in the symposium included a recent alum of the biology department and two women who currently have post-doctoral positions in aquatic and fishery sciences. Biologists are also found in forest resources, oceanography, marine affairs and health sciences.

The next WEBS symposium is planned for Oct. 19-22, 2008.