November 17, 2005

Russian director brings Chekhovian experience to drama school’s ‘Cherry Orchard’

Audiences may come to remember the UW’s 2005 production of Anton Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard, set to run Nov. 28 though Dec. 11 at the Penthouse Theater, as a near-definitive interpretation of the century-old classic. The creative guidance of esteemed Russian director Leonid Anisimov will likely see to that.

Anisimov, whose English is limited, sat down on a recent afternoon to talk a bit (with the help of translator Wes Hurley, a School of Drama graduate) about Chekhov in general and the coming production in particular.

“One thing I can promise for sure,” he said. “(The audience) will see the most Chekhovian production possible — as close to Chekhov (as you can get) in the modern world.”

Anisimov ought to know. He was trained at the Moscow Art Institute, was co-founder of the International Stanislavski Academy and, until recently, was artistic director of The Chekhov Theatre of Vladivostok. He also has been named an Honored Artist of Russia, the highest recognition possible in that country.

Locally, plays directed by Anisimov have earned soaring praise in recent years. The Weekly, one of Seattle’s alternative papers, described the acting in an Anisimov-directed production of Chekhov’s The Seagull as “moments laid lovingly down like pearls on velvet, each one with rich luster.” The Stranger, the other alternative weekly in town, said the production was “quite simply, what live theatre should be.”

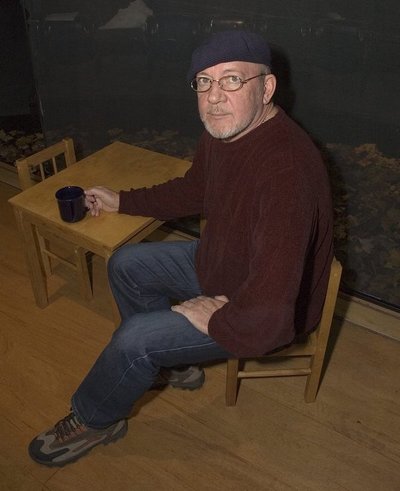

The fact that Mark Jenkins, director of the UW’s Professional Actor Training Program, is playing a key part in The Cherry Orchard only makes a more compelling case for the production’s excellence. It’s Jenkins’ first stage role at the UW in his 15 or so years here, though he is a vastly experienced actor who has performed elsewhere in recent years. How did Anisimov get Jenkins to take the pivotal role of Firs? Jenkins joked in response: “He pressured me into it.”

In fact, the two have worked together several times and have a sort of mutual admiration society going. Of Jenkins, Anisimov said, “He’s my best student, my most beloved and the best. He has a very open heart — the kind of heart you want to give everything.” Jenkins, in turn, said of Anisimov, “He’s as close to a genius as I’ve been around professionally. He’s got a very particular and incredibly sensitive perception of things.”

The Cherry Orchard, first produced in 1904 — 13 years before the Russian Revolution — is the story of a family dealing with its decline from the aristocracy and the inevitable need to dismantle its estate and chop down its beloved orchard to meet taxes and pay debts.

Asked the theme of the play, Anisimov considered his words a moment, then said, “There is something about to be gone, and something new to come in its place. What’s leaving is beautiful; what’s new is funny.” He thought a moment, then added, “What’s old is graceful and fine, and what’s new is very crude.”

Still, the age-old question remains: What is it to be properly Chekhovian? Is it comedy, as the author often claimed, or heavy drama, as lengthy stage tradition implies? Are we to laugh or cry at the failures, the foolishness, the longing sadness and glue-like immobility of Chekhov’s characters?

The author himself went to his grave sadly convinced people weren’t catching on to the intended lightness and humor in his writing. He even felt that the now-legendary acting theorist and director Constantin Stanislavski, with whom he often worked, missed the point.

Anisimov, also an expert on Stanislavski, said, “Chekhov is funny in an irony sort of way. It looks at people as if they are small children. Little children can cry, and the adults can smile.” Does he expect outright laughs from the audience through the Chekhovian gloom? “I expect smiles,” the director said. “And I expect points of laughter — the kind of laughter that comes from understanding.”

He said Chekhov would say “You have to laugh when you part with your past,” but that Stanislavski, somewhat annoyed at this, countered that such a view might be humorous to some, but to regular, work-a-day people, sweeping, irreversible change often means tragedy.

Just as Anisimov knows what audiences should expect from his production, he also knows what to expect from his actors at the UW, a skill borne of 30 years’ daily work in the theater. He said part of his mission is to teach American students about “inner action,” or the controlling of one’s energies. “The art of an actor is the art of energy,” he said, and soon added, “Inner action is the foundation for the creative process for any actor.”

Part of this process, to Anisimov, is the theory of “reliving,” which he has long taught and which he said is similar to what Americans have come to know as “method acting.” Asimimov said many actors mix up the ideas of “emotions” and “feelings.” The former, he said, are more fleeting and superficial, while the latter are deeper, arising from elements of memory, circumstances and energy. “To develop feelings is not enough,” he said. “You need reliving.”

Chekhov helped usher realism to the 20th century stage while also being linked to other forces delving into the delicious chaos of the absurd. Jenkins said, “Historically, dramaturgically, Chekhov sort of threw out all the conventions of theater up to that point — things like plot, resolution, dramatic arcs — and replaced them with a much more subtle interaction.” He noted that it’s often said of Chekhov that “people’s fates are sealed with the passing of a teacup.”

Of this production, Anisimov said, “I think the audience will be surprised, but the surprise will depend on the consciousness of the audience members. Some might be more surprised than others.”

For his part, Jenkins said the show will be “unlike any Chekhov people have seen before.”

Different, yes — but also possibly definitive.