June 3, 2010

Law student was once a defendant, now plans to be a defender

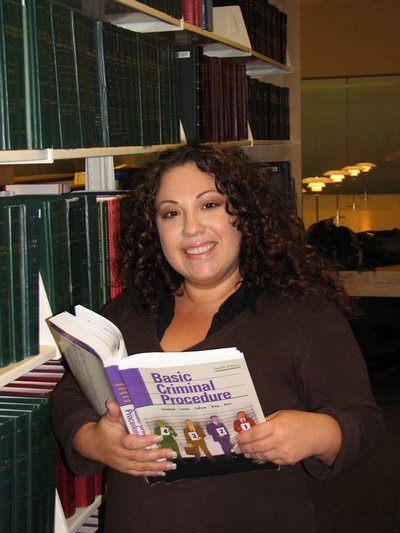

When Alena Suazo graduates from the UW School of Law in June, she’ll have the degree that qualifies her for the public defender job she wants. She’ll also bring other experience to the job.

Suazo, 30, was a member of a street gang in Camarillo, Calif. for nearly seven years as a teenager. Drugs, alcohol and petty crime were routine parts of her life. She also served time in jail after a juvenile conviction.

It’s been a long road, beginning with parents who wanted a lot for their daughter.

“I had really, really good parents,” said Suazo, who was raised by her mother and a stepfather who adopted her.

“My father really wanted to take advantage of the American dream,” she said. Miguel Suazo worked a day shift at a grocery store; Suazo’s mother, Debbie Suazo, worked the night shift so one of them could be home with their daughter. Miguel eventually became manager of the store’s produce section but then became ill and couldn’t work, so Debbie became the breadwinner. At the time, their daughter was about 13.

“My mom was really, really preoccupied with working and taking care of my father. I had to learn to be self sufficient. I turned to the neighborhood to find support,” Suazo said.

The Camarillo gang was multi-generational. Parents and grandparents had belonged. Suazo’s school and neighborhood friends belonged, and the gang became sort of a family for her.

“We hung out together, smoked pot, drank, were boy crazy, went to other neighborhoods and fought with other girls,” Suazo recalled. “It was a bunch of kids who loved and looked out for each other but didn’t have adult support.”

“When I was 15,” Suazo said, “I got caught stealing a car.” That led to several weeks in a juvenile detention center.

“My parents sort of freaked,” she explained. “They didn’t know how to deal with it.” Debbie Suazo made it clear that her daughter’s actions were making Miguel sicker.

Suazo assured her parents that she’d straighten out, but in the first semester after detention she skipped 45 days of school. In the meantime, Miguel Suazo was back at work but remained in poor health.

Suazo did poorly as well. “I went downhill,” Suazo recalled. “Drugs, drinking, partying…” Asked what kind of drugs, she said, “Meth, crack — everything except heroin. I had no path, no plan. My life was just ‘right now.’ I never thought about the future.”

In an alternative school, girls from a rival gang jumped Suazo, and all including Suazo were kicked out. Debbie Suazo then asked the local high school if it would take her daughter back. As a favor, administrators said yes.

“The freshman principal was the only person in the school who cared about me and my group. She worked with me, my friends and our families. We got second, third and fifth chances,” Suazo said.

But Suazo eventually went to another alternative high school and continued to go nowhere. Nobody demanded performance, and simply doing the work was a challenge. Students didn’t receive individual textbooks. If they wanted to take one home, they had to check it out at the end of the day and return it in the morning.

One day in class, a girl from a rival gang began punching Suazo. The school had a no-tolerance policy about violence, so both Suazo and the other student were expelled.

“It was really awful because I was doing well; at the rate I was going, I would have graduated in a year,” Suazo recalled. “I was still doing the other stuff (drugs, drinking, partying) but was taking school seriously. I wanted to make my parents happy.”

Suazo then landed in another school where she was placed in a class designated for troublemakers. She also continued in the gang. “My mom kicked me out of the house 17 times, and I probably ran away another 17 times,” Suazo recalled.

But the whole routine was getting old. About the same time a close friend died of a drug overdose.

“I wanted to go into rehab,” Suazo said. “I just got sick of being on drugs. I was just tired and wasn’t doing anything with my life.” Thanks to a rehab center, she quit drugs and graduated from high school through independent study, but she didn’t quit the gang.

Eventually, without a job or a plan, Suazo stole again. For several days, she was in jail.

Once out, Suazo went back to her friends. But one day when she was 19, members of a rival gang attacked her and two friends in her car, all but destroying the car and leaving the young women badly bruised.

Suazo’s parents decided it was time to move to Billings, Montana, and while Suazo swore she wasn’t going with them, she changed her mind at the last minute.

In Billings, Suazo met and married a man who was in the Navy. But she never fit with his friends, as they had backgrounds and worldviews different from hers. They spoke disparagingly of other races.

“I was ashamed of my background, but it was a catalyst for me,” Suazo said.” I figured if I went to college, I could talk about things besides jail and drugs.”

She began classes at a community college, then went to Chaminade University in Hawaii, where she changed her major from math to historical and political studies. She also got interested in law. The study of history, particularly slavery and Native American genocide, had made her more deeply aware of law and its impact on communities of color.

She began thinking about law school, even though she’d never known a lawyer nor had any idea what the experience would be like. “I just knew,” Suazo said, “that a person could do so much with a law degree. I believed I could use a law degree to make positive social change.”

The UW School of Law accepted her, but her initial time at the University wasn’t easy. As a Latina who’d struggled to pay for education and had spent no time around people with even middle-class pay checks, much less upper-class ones, she felt isolated. “It was a total shock, and I internalized it; I felt like an imposter,” Suazo said.

Eventually, however, determination kicked in — the same kind that had sprung her from the gang and into college.

She served on the UW Law School Diversity Committee. She co-chaired the Latina/o Law Students Association. She mentored a young woman who was in juvenile detention. These days, she works in the UW Student Legal Services.

Brenda Williams, a lecturer at the law school, saw the advantages of Suazo’s history when she participated in the tribal court public defense clinic. “Her background probably contributes to her ability to connect with clients of the clinic because they view her as a regular person,” Williams said. “She’s passionate about justice and never hesitates to speak for the underdog.”

After graduation, Suazo plans to spend at least nine months visiting Africa and South America on a Bonderman Travel Fellowship, which provides $20,000 for at least eight months of independent international travel.

Eventually, she wants to be a public defender because she understands the importance of legal representation, particularly if a person is poor and doesn’t know the legal system. “I’ve been fortunate — or unfortunate,” she said, “to have had the experience of having to have a public defender.”