April 8, 2010

Of salmon and the stage: UW anthropologist’s research comes to life as a play

It’s Complicated, might be the title of Sara Breslow’s dissertation. Or it might be The Last Best Place. The former is what she’s learned from her research; the latter is one of its products — a play that has already had two readings and is headed for a third.

A play? As in, a piece of literature performed on a stage? That’s right. With the assistance of a playwright, Breslow turned excerpts from her research into a theatrical script, but she’s also writing a more conventional dissertation that should earn her a doctorate in anthropology before the year is out.

She didn’t set out to write a play, of course. In fact, she went into her adventure 10 years ago with no theater experience whatsoever. Back then, Breslow had just started graduate school in environmental anthropology (that program has since been discontinued), and a colleague begged her to take over a summer internship she’d secured that was sponsored by the Environmental Protection Agency and the Society for Applied Anthropology. It was in the Skagit Valley, and it asked a seemingly simple question: Why aren’t more farmers in Washington State signing up for a federal program to voluntarily plant buffers of trees along rivers and streams for significant financial compensation?

The buffers were designed to help restore habitat for salmon, and the federal government was willing to pay farmers well if they would set aside some of their land for them.

“So I went about asking that question over a three-month period,” Breslow recalled. ” I interviewed about 20 farmers that summer. And what I realized was … it was a very heated controversy and I was completely new to it. I really got an earful.”

The farmers felt that they were being asked to give up too much land — in some cases so much that they would be forced out of farming. They felt the program would create negative byproducts such as invasive plants and rodents and wouldn’t work to restore salmon habitat anyway. Complicating the issue was the fact that while the federal program was voluntary, the state Growth Management Act was about to mandate that farmers create buffers.

“What I learned was that the reason farmers weren’t signing up for the federal program didn’t have much to do with the federal program,” Breslow said. “It was a story that had a lot of sides to it and I was aware that I was only getting one side of the story.”

So when she had a chance to return to the Skagit Valley the following summer to help do an oral history of fishing and fisheries management in the valley, she took it. More interviews followed — this time of fishermen and fisheries scientists.

“Two or three years later I came up with a dissertation proposal that was focused on conflicts surrounding efforts to restore salmon habitat on private farmland,” Breslow said. “My question was, why is there a conflict?”

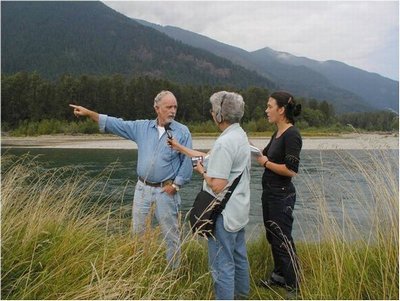

Again, it sounds like a simple question. But it isn’t, as Breslow soon learned. She lived in Mount Vernon for 18 months — networking through multiple communities, going to meetings and doing interviews. She found out that many groups were embroiled in the issue — farmers, fishermen, environmentalists, scientists, government agencies and one of the local Native American tribes.

Meanwhile, she reached a point of personal frustration.

“Part of what I enjoyed [about the research] was being in the presence of the person, and hearing their voice, just the quality of their voice — different ways people spoke the English language,” Breslow said. “So, anticipating writing an academic dissertation on this topic, I felt like a lot would get lost in transferring my ethnographic experience into text. And I’m an artist at heart. I felt there was this whole part of me that was checked at the door [of graduate school]. I wondered if I could let any of that in.”

Breslow took her concerns to then-chair of the Anthropology Department, Mimi Kahn. It was Kahn who suggested that Breslow might explore the idea of a play. And her adviser, Eugene Hunn, was open to the idea. With some trepidation, Breslow attended a panel discussion following a play at Intiman Theatre, and approached the artistic director with her idea. The director suggested she contact playwright and actor Todd Jefferson Moore. The two began working together, and ultimately became co-authors.

With Moore’s guidance, Breslow began by poring through her voluminous material, looking for the most dramatic excerpts. These she sent to Moore. Together they culled 100 pages worth down to something that seemed manageable. Breslow tried reading the material to selected audiences, most notably, Professor Steve Harrell’s undergraduate anthropology class. The class pleaded for a narrator to help them understand how everything tied together, and suggested that the anthropologist be the narrator. Thus, Breslow became a character in her own play, which came to be called The Last Best Place.

Moore, meanwhile, was trying to advise her on how to make what she had dramatically compelling. As someone who had produced documentaries, he knew that interviews alone wouldn’t be enough to hold an audience. Moreover, there were methodological differences. “Sara’s interviews were done as a scholar,” Moore said. “That’s different from when you interview for a documentary. And this material is complex. We had to find a way to help the audience understand the complexity without boring them.”

In the end, they did it by letting many of Breslow’s interview subjects speak for themselves, after her character (to be played by an actress) introduces them. At times there’s a rapid interplay between the anthropologist and her subjects, as when a farmer is discussing the proposed buffers. Breslow changed everyone’s names and at times did other things to hide their identities, but she still worries about using their words and accurately representing their positions.

In fact, being portrayed in the play herself intensified her sense of responsibility to her subjects, Breslow said. “The theater people involved sometimes wanted to take poetic license with my character to make things more dramatic, but I worried about how that would affect my work,” she said. “It made me doubly concerned about representing my subjects fairly.”

Her concerns, so different from a dramatist’s, made working together both wonderful and agonizing, Moore said. “She came from her world, I came from mine. I wanted passion and conflict, but in science passion is diminished.”

For her part, Breslow said, “I’m sometimes oblivious to the dramatic qualities but I’m so concerned with accuracy, ethics, issues of representation.”

The play has received two readings — one for Breslow’s family, friends and colleagues, and the second, sponsored by Seattle Repertory Theatre, to which the Skagit Valley people were invited. Their response was generally positive, Breslow said. And she’s currently talking to a project manager at the Nature Conservancy, who would like to present the play in the Skagit Valley, possibly this fall.

Moore thinks the play has a future as part of an educational process: present the play and stage a discussion afterward. He’d like to see it presented in Seattle and says that in addition to the Nature Conservancy, the Environmental Protection Agency and the Puget Sound Partnership are interested in it. That would fulfill some of Breslow’s hopes, as expressed in her program note for the play:

“I often wished I could invite farmers to listen to interviews with Indian people, or to invite restoration advocates to listen to interviews with farmers. Perhaps if they sat, like I did, in each other’s living rooms and offices and simply listened for an hour or two, they would begin to see a way through their differences. I realized that through theater I could bring these interviews to life — onstage, and maybe even in the audience. A play, unlike a dissertation, requires its audience to come together in the same room — perhaps for the first time, and witness a conversation that until now has only taken place inside my head.”