April 23, 2009

UW professors follow ‘The Modern Girl Around the World’ in new book

Before the TV show Sex and the City made popular the image of the successful, independent, Cosmo-sipping woman of the new millennium, there was the Modern Girl, a worldwide figure of the 1920s and 30s who dressed provocatively, sought romantic love and seemed to buck the roles of dutiful daughter, wife and mother.

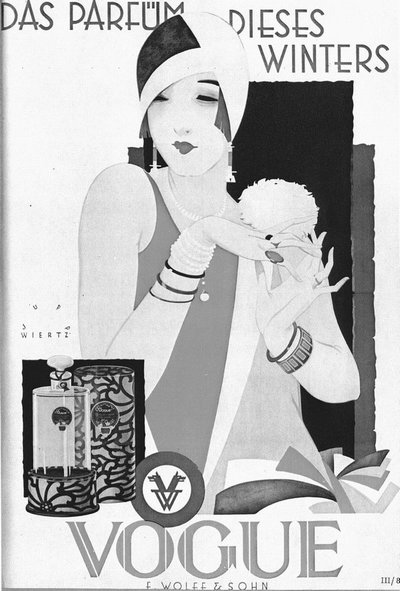

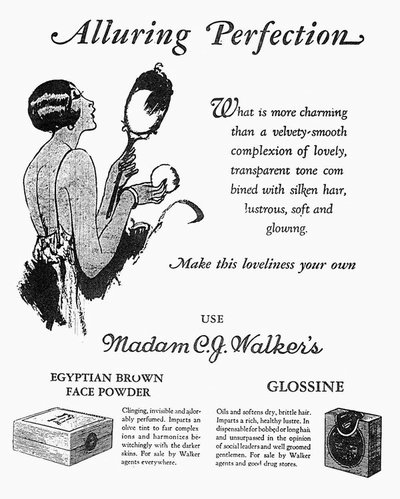

Recognized in North American culture as a “flapper,” the Modern Girl was characterized by bobbed hair, painted lips, high heels and an open, easy smile. She was a symbol of sexual, economic and political emancipation for women, but also a source of anxiety for those wary of her newfound independence and sexuality.

This modern female figure is the subject of The Modern Girl Around the World: Consumption, Modernity and Globalization (Duke University Press, 2008), a new anthology written and edited by the UW-based Modern Girl Around the World Research Group.

The research group comprises Priti Ramamurthy, associate professor of women’s studies; Alys Eve Weinbaum, associate professor of English; Madeleine Yue Dong, associate professor of international studies and history; Uta G. Poiger, associate professor of history; Lynn M. Thomas, associate professor of history; and former UW history professor Tani E. Barlow, who now teaches at Rice University.

The group spent seven years tracking evidence of the Modern Girl’s existence around the globe in the form of both real women and images in films, advertisements and illustrated magazines. The members had all encountered the figure in earlier research and saw the potential to learn more about how capitalism impacted women and their femininity around the world.

They initially set out to study the Modern Girl’s emergence over different time periods, but their research revealed that her image bubbled up simultaneously in cities from Beijing to Bombay, Tokyo to Berlin, and Johannesburg to New York in the period between World Wars I and II.

“This figure of the Modern Girl emerged simultaneously with forms of capitalism,” Weinbaum said. “It was very exciting to people in the group because we were trying to understand the material conditions of that emergence.”

The simultaneous appearance of the Modern Girl around the globe refuted prior assumptions that modernity had originated in Europe and North America, and then was emulated by the rest of the world. This discovery led the research group to believe that the Modern Girl did not originate in one place, but was rather an image influenced by multiple cultures, as well as each local culture in which she appeared.

The group developed a concept called multidirectional citation to define the multiple influences that shaped the Modern Girl’s image.

“The idea was to de-center the U.S. as the source of this modernity,” said Weinbaum. “In all the locations in which it was emerging, it was impacting the other locations in complex ways that needed to be understood and examined, instead of just imagining a figure that emerged in silent film and American advertising and was disseminated around the world by American businesses.”

Having come from different academic backgrounds and cultural specializations, each of the research group members focused on the Modern Girl in the context of a specific country in individual chapters, including South Africa, China, India, Germany and the U.S. Additional contributors examined her image in Australia, Japan, Russia and Zimbabwe. The resulting anthology analyzes how global commodities, like clothing, cosmetics and film, flowed across geopolitical locations to shape modern femininity.

The group’s multidisciplinary approach to the project was both challenging and rewarding, said Ramamurthy.

“We really struggled with the approaches that our disciplines had taught us to bring to bear on the question of what the Modern Girl was and what kind of work she did in different locations,” Ramamurthy said. “I think that some of the most challenging and most productive discussions were about what kinds of methodologies we use, the kinds of truth-claims that we were looking for. This is actually one of the things that we most enjoyed about the project.”

Although the Modern Girl no longer exists in culture the way she did in the 1920s and 30s, cultural anxiety about her sexuality and independence can be compared to the anxiety — or lack thereof — about today’s modern girl.

“Certainly there is still much anxiety about female sexuality, but we now see ways in which female sexuality and sexual expressiveness are deployed as signs of modernity and Western superiority,” Poiger said. “You see that, for example, in debates in Europe about such aspects as veiling, where being unveiled — but more generally, being sexually expressive — is seen as a sign of the healthy, modern woman.”

And interest in the Modern Girl goes beyond the research group, they said — students of history, women’s studies and international studies have all been fascinated by this historical figure.

“Almost all of us have taught courses on the Modern Girl in our departments for undergraduates,” Weinbaum said. “There is a resonance with contemporary struggles around identity and self-creation. While the historical times have changed, the kinds of struggles that she was involved in remain relevant for young people who are thinking about what it means to be a girl.”

The Modern Girl Around the World Research Group will give a presentation about The Modern Girl Around the World: Consumption, Modernity and Globalization on Wednesday, April 29, at 4 p.m. in 202 Communications. The presentation, sponsored by the Simpson Center for the Humanities, is free and open to all. A reception will follow.