April 9, 2009

UWT prof transcends art world to bring the world into her art

Recently, someone asked Beverly Naidus why she gave up the glamour of the New York art world to teach socially engaged art to college students — on a university campus that doesn’t even have an art degree.

Naidus didn’t flinch.

“I told her, ‘I don’t think you understand,'” Naidus says. “The art world is not enough. We have to be doing more in this time, and I have to be teaching.”

It wasn’t enough, she explains, to be making art that exposed the tragedy of chemically caused illness, nuclear nightmares, women’s body hate, racism and exploitation of the environment—some of the subjects typical in Naidus’ art. She needed to spread her message on a broader scale.

“The world is a mess, and we need to be out there getting other people involved in transforming it into something better,” she says.

Naidus, an associate professor in UW Tacoma’s Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences program, cut her artistic teeth in New York City. As an 11-year-old, she learned to ride the bus into the city from New Jersey and began visiting museums. All forms of art interested her, from dance and theater to painting and poetry, as a way to process her thoughts.

“My parents were the children of immigrants,” she says. “The dream was for me to become a businesswoman, a lawyer, a scientist or a doctor. But I had an affinity for the arts. Art helped me find coherence in a very chaotic and confusing world and helped me to feel less alienated and more empowered.”

In high school, Naidus considered anthropology or sociology as a career until a teacher told her she had an artistic gift. But she still hesitated. Family members warned her away from a career in art, she says. “I heard, ‘Don’t be an artist. Don’t be an artist. You’ll starve.'”

In college, though, Naidus realized she could do both: study all of those “serious” topics and make art about it.

“Art making gave me a frame in which to process all the things I didn’t understand, and it also allowed me to integrate issues in new ways,” she says. “I never went back to tell that high school teacher he was right. But I did send him announcements for my exhibitions in New York.”

Naidus has always created very personal art—for her, it’s a way of working through intense emotions and complicated ideas. She processes nightmares, pain, rage and self-doubt in her work. In the 1980s, while she was living in Southern California, Naidus began to feel ashamed that her body didn’t look like the models in magazines and concerned for her feminist friends, who were all on diets. She researched the causes of women’s body hate. A passionate series of drawings and collages led to the publication of a book (One Size Does Not Fit All) and, eventually, a course at UW Tacoma called “Body Image and Art.”

Illness and environmental issues are other themes that run through her work. Smog and pesticides in the Los Angeles area gave Naidus an environmental illness and eventually provoked her to give up her tenure at Cal State Long Beach and move away. She turned that experience into another body of art work — Canary Notes: the Personal Politics of Environmental Illness — and UW Tacoma class, Eco-Art: Art Created in Response to the Environmental Crisis. Her art has also focused on cultural identity, racism, war, global warming, genetically modified food and more.

In her courses, students are encouraged to examine their lives, their communities and the world as well as art. It’s common to see groups of her students engaging in art projects that express social messages. One year, students set up shop in the central campus square and encouraged passers-by to lie down and have their outlines drawn in chalk. The result was a celebration of body shapes and sizes. Another class addressed the human cost of war with an anti-war installation that prompted debate across campus (with many naysayers unaware that some of the student artists were veterans themselves). For a recent class, students invited women from across campus to join them for a series of photos that captured their individuality and strength.

“I have been so blessed to have students who are just on fire after they take my classes,” she says. “Many of my students have had very little exposure to art. In our classes they have an opportunity to learn about social issues of interest to them, like body image, war, labor or globalization, develop some formal skills and then tell their own story in an art work.”

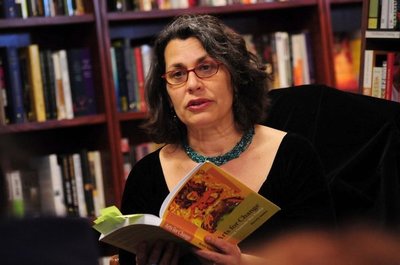

Naidus’ career in education inspired her latest book, Arts for Change: Teaching Outside the Frame (New Village Press, 2009). The book explores the motivations and challenges of teaching socially engaged arts in a university setting and includes the stories of 33 other practitioners around the world. Part of her intention is to help other art instructors successfully engage students and teach them to use art to raise consciousness.

Naidus continues to exhibit her work, and more recently has begun to use her art to imagine a healed world rather than focusing on its problems. She and another artist are currently turning part of the Beall Greenhouses on Vashon Island—an historic area now full of toxic soil—into a sacred garden filled with audience-participatory altars to seeds using permaculture. Naidus, a Vashon resident, calls it “eco-restoration art.”

In the meantime, she’s created a new interdisciplinary arts curriculum for UW Tacoma and has co-created a new major, Arts in Community, that awaits funding and approval.

“It would be wonderful if we had this version of an art major,” she says. “But I’m just grateful that we’re able to do what we do in this program. We need art in this time, probably more than we ever have before. People are in such deep states of despair and fear right now, and art allows us all to see the world in a new way and imagine how to create a better one.”

Naidus will read from Arts for Change this summer at the Elliot Bay Bookstore in Seattle. The date of the reading has not been set. Check www.artsforchange.org for details and more information about the book.