March 5, 2009

A dead gene comes back to life in humans

Researchers have discovered that a long-defunct gene was resurrected during the course of human evolution. This is believed to be the first evidence of a doomed gene — the infection-fighting IRGM — making a comeback in the human/great ape lineage.

The study, led by Evan Eichler’s genome sciences laboratory at the University of Washington and the Howard Hughes Institute, is published March 6 in the open access journal PLoS Genetics, in the article, “Death and Resurrection of the Human IRGM Gene.” The first author of the study is Cemalettin Bekpen, a UW senior fellow in genome sciences.

The truncated IRGM gene is one of only two genes of its type remaining in humans. The genes are Immune-Related GTPases, a kind of gene that helps mammals resist germs like tuberculosis and salmonella that try to invade cells. Unlike humans, most other mammals have several genes of this type. Mice, for example, have 21 Immune-Related GTPases. Medical interest in this gene ignited recently, when scientists associated specific IRGM mutations with the risk of Crohn’s disease, an inflammatory digestive disorder.

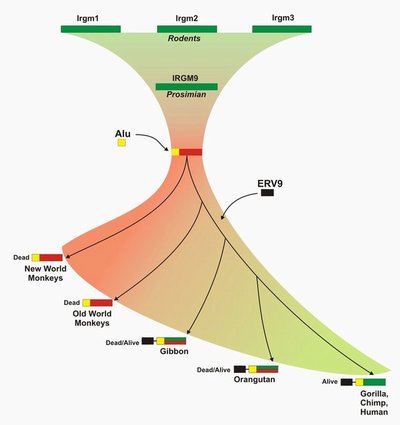

In this latest study, the researchers reconstructed the evolutionary history of the IRGM locus within primates. They found that most of the gene cluster was eliminated by going from multiple copies to a sole copy early in primate evolution, approximately 50 million years ago. Comparisons of Old World and New World monkey species suggest that the remaining copy died in their common ancestor.

Like an incomprehensible ancient text, this gene remnant continued to be inherited through millions of years of evolution. Then, in the common ancestor of humans and great apes, something unexpected happened. Once again the gene could be read to produce proteins. Evidence suggests that this change coincided with a retrovirus insertion in the ancestral genome.

“The IRGM gene was dead and later resurrected through a complex series of structural events,” Eichler said. “These findings tell us that we shouldn’t count a gene out until it is completely deleted.”

The structural analysis, he added, also suggests a remarkable functional plasticity in genes that experience a variety of evolutionary pressures over time. Such malleability may be especially useful for genes that help in the fight against new or newly resistant infectious agents.

In addition to Eichler and Bekpen, other researchers for this study were Tomas Marques-Bonet, UW Genome Sciences and Institut de Biologia Evolutive, Barcelona, Spain; Can Alkan, UW Genome Sciences and Howard Hughes Medical Institute; Francesca Antonacci, Jeffrey M. Kidd, and Priscilla Siswara, UW Genome Sciences; Maria Bruna Leogrande and Mario Ventura, Universita degli Studi de Bari, Italy; and Jonathan C. Howard, Institute of Genetics, University of Cologne, Germany.

The work was supported by National Institute of Health grants, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and a Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft grant.