July 10, 2008

Hawaiian park reborn, thanks to UW students

For Iain Robertson, a UW landscape architecture professor, Kahalu’u Beach Park turned out to be one of the most fascinating projects he’s ever worked on. For Leslie Gia Clark, a UW graduate student in landscape architecture, reconceiving the park meant a journey beyond fast cars and big box stores into the heart of Hawaiian culture.

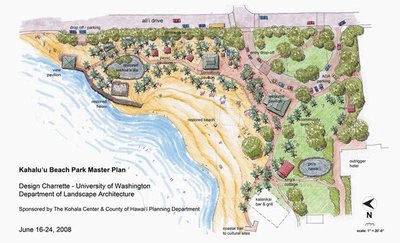

And for Cindi Punihaole, as well as the members of the Kahalu’u community, a master plan for the park has become the first step towards a reborn park, something they’ve dreamed about for years. Robertson and five of his students spent five days in mid-June studying Kahalu’u and talking with members of the community, then drafting a master plan.

Hundreds of years ago, the team learned, Hawaiian royalty built homes and temples on and around the 4.5-acre park site. “We were sitting on one of the richest historical and cultural sites on the islands,” Robertson said. His team had to consider not only how to honor and restore sacred spaces but make provisions for education and recreation, as the park is one of the most used on the island of Hawaii, the largest in the Hawaiian chain.

The team also learned that the Kahalu’u beach is eroding and a coral reef offshore is being damaged by a variety of beach users, including snorkelers.

Renewing the park is a big order, acknowledged Punihaole, who is outreach and volunteer coordinator for the Kohala Center, a not-for-profit institute for environmental research and education on the island.

Punihaole and Brad Kurokawa, a UW graduate in landscape architecture and deputy director of planning for the County of Hawaii, knew that without a master plan, there was no point in talking money with politicians or philanthropists. Kurokawa thus recruited Robertson, with whom he had worked in Seattle. For the price of plane tickets and some donated hotel rooms, the two men made a deal for a Kahalu’u master plan.

The work, including drawings, would have to be done fast — inside of five days. Eric Streeby, a second-year bachelor’s student, said he and other students quickly felt the responsibility. “This was a real-world situation, and a lot of people’s hopes were riding on the plan, so we tried to come up with a design that incorporates everyone’s wishes.”

Some of the island families have ties to Hawaiian royalty and continue to own strips of land between ocean and mountains. In three public meetings with the UW team, they and others said they wanted several park spots restored, including a bathing pond once used by royals. Another pond eastward, the Po’o Hawaii, has been restored and marks the spot where King Kamehameha I, who united the islands and ruled from 1795 to 1819, once had a home.

The community also wants restored the foundation of a heiau, a Hawaiian temple and one of several inside Kahalu’u. When Christianity came to the islands in the 19th century, the temples fell into disrepair, and except for some old foundations, they no longer exist in the park.

Hawaiian cultural masons would help restore the heiau. According to Punihaole, they would lay carefully chosen stones in a particular way, but only after asking blessings from kupuna (ancestors).

The master plan presented at the third meeting includes a restored heiau. It also includes recreation areas such as an imu, or pig-roasting pit. It’s north of the Outrigger Keauhou Beach Resort, which borders the south side of the park. If a fence between the park and the hotel were removed, said the team, it would integrate land use.

For educational and community programs, the team recommended restoring one pavilion in the center of the L-shaped park and adding a second.

It also recommended hiring a coastal geologist to determine how to restore the beach, possibly by removing several seawalls.

Clark, the graduate student, was struck by the sheer differentness of Hawaii. “We grew to understand both the ecology and the uniqueness of the culture. It’s really an isolated environment.”

She also realized that the meetings were the first serious conversations about restoring the park, and that architectural drawings could move dreams forward.

When the UW team presented its drawings at the final meeting, members of the Kahalu’u community said mahalo. In Hawaiian, it means a heartfelt thank you.