March 6, 2008

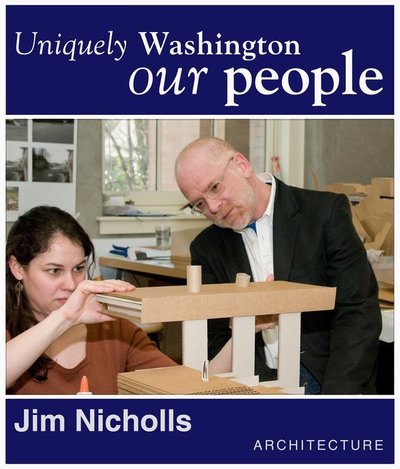

Architect was inspired by television’s talking horse

Jim Nicholls thinks that maybe he became an architect because of Mister Ed. Most people recognize that as a family TV show of the early ’60s that featured a talking horse, but they might not remember that the horse’s human companion was an architect.

“He had a pretty nice lifestyle,” Nicholls recalls. “He had a little barn out in back, and he walked from the house to his studio, where he drew and made models all day.”

Whether it was because of Mister Ed or not, Nicholls studied architecture at the University of British Columbia and worked at a firm in Vancouver, BC, for 10 years. Then he had a chance to come to the UW on a two-year contract. Twelve years later he’s still here as a senior lecturer in architecture.

Nicholls calls his specialty “architectural outreach,” by which he means taking students out into the community to work on real life projects. It all started five years ago, a few blocks away in the U District. Store owners on the Ave. had been offered matching funds from the city to improve their facades, but there had been few takers. So Nicholls and a group of graduate students set up shop in the vacant Tower Records store and began offering assistance to the owners.

“In addition to bringing in individual owners we staged a series of open houses where we brought in as many people as we could,” Nicholls says. “We printed out big poster-sized images and put up displays, so we turned the storefront into a gallery.”

The improvement to the streetscape that resulted impressed the City of Seattle and King County so much that every year since then, Nicholls has done a Storefront Studio in a different community, sometimes two. Students have been to Renton, Carnation, Auburn, White Center and Kent. This spring they’ll be going to Des Moines.

Each community project involves a different assignment. In Kent, for example, the students looked at how the community might improve the section of the city that commuters see from the train tracks. In Des Moines, the mandate is to figure out how to make people more aware of the waterfront, which is only a few blocks from Main Street but unconnected to the downtown.

In each case, the students set up shop in a vacant storefront and begin to document what they see. One of their first assignments is to create a postcard of the community. A place like Seattle, Nicholls explains, has famous spots like the Space Needle and Pike Place Market that appear over and over on postcards. In places like Kent or Des Moines, it’s not as obvious what might be placed on a postcard. So the students go out with cameras and capture what they think are postcard scenes. Then, like someone writing on the back of a postcard, they describe the scene in story form.

“Doing this assignment slows the students down and gets them out on the streets looking closely at what’s around them,” Nicholls says. “If you put 12 or 16 of these postcards up, you get a picture emerging in the composite.”

Students then spend a lot of time talking with people in the community and using their computer programs to do “virtual remodeling,” showing their clients what particular changes to their property would look like.

Nicholls loves watching the transformation the students undergo — from students to resident experts, respected by the people in the communities who have hired them; and often, from looking down on the small communities to appreciating them.

It’s all part of his aim as a teacher. “I want my students to look at the world as if they’ve never seen it before,” he says. “I can give them some tools and some facts, but what I most of all want them to do is start their own intense inquiry that’s about opening their eyes and looking around the world with fresh new vision.”