February 28, 2008

Center for Educational Leadership: Coaching teachers, others to help students

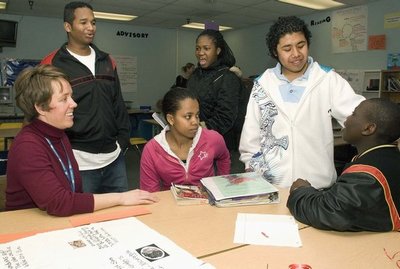

To see students and teachers working together at the Academy for Citizenship and Empowerment in Sea-Tac, it isn’t immediately obvious that the school has been getting assistance from the UW’s Center for Educational Leadership.

But talk to the teachers and the coaching and motivation provided by the center — also called simply CEL — shines through quickly.

“This work has improved my practice tremendously,” said teacher Michelle Lobb in an e-mail. “I feel through observing students’ behavior and looking at their work I have been able to develop outcomes to better meet their needs.”

“I would have been afraid to do this before,” said teacher Bethany Plett as she watched her class of English language learners share stories of their homelands in small groups. The informal seating, with its collaborative feel, came straight from the coaching. “It’s totally nonthreatening,” she said, the contented buzz of the students proving her point.

The Center for Educational Leadership operates through the UW College of Education but is fully self-sustaining. It has about 15 people on staff full or part time and about 30 consultants nationwide. Now in its sixth full year, its mission is to reduce the student achievement gap — the nationwide concern about differences in student achievement related to race, gender and socioeconomic status.

The center’s work is based on the idea that teacher effectiveness is key to closing the achievement gap. It operates under the following three basic assumptions:

- The achievement gap will be eliminated only when the quality of instruction in the classroom improves.

- The quality of instruction will improve when school leaders know what powerful instruction looks like.

- When school leaders understand powerful instruction, they can lead and guide professional development, target and align resources, engage in problem solving, and build the capacity of teachers.

Toward that end, the center partners with school districts to give assistance at all levels of instruction, as well as leadership coaching for principals and central office leaders, along with leadership networks for district superintendents. The center tailors its work to fit the needs of each client.

Just now, the center has partnerships with more than a dozen school districts, primarily in Washington and Oregon, but also in California, Wyoming and Louisiana. In all, the center interacts with 27 different districts, providing partnerships, programs or other services.

The center has been working with the Highline School District for about five years now, assisting at all levels of instruction. Its multifaceted intervention in schools resists simple explanation, but one telling comment came from Plett and other ACE teachers unbidden: The center, they said, has helped them break free of the rigid, lecture-style “stand and deliver” model of teaching.

Plett and other ACE teachers got personal assistance from Jennifer McDermott — whom they call Jenn — a teacher-turned-consultant who provides “embedded coaching” for CEL. That’s where the coach works virtually side by side with a teacher in the classroom setting.

McDermott explained, “Classroom coaching is the majority of my work… 90 percent of the time I’m working with cohorts or individual teachers in their classroom — sometimes one on one and sometimes with visiting teachers.”

This is more comfortable and effective than sending teachers to daylong workshops held once a year or less often, where the idealism of the class soon fades when they return to the reality of their daily challenges.

Carrie Howell, who teaches 12th-grade language arts and mass media at ACE, said in an e-mail, “I’ve been in many professional development classes and workshops” over seven years at ACE, “but nothing has been more formative and supportive than the coaching I have received from CEL.

“The embedded coaching (where the coach works with me in my class with my students) is invaluable because it meets me where I am in my instruction. My coach knows me and my students and she helps me to see where I can go and what I can do to better support them in their learning.”

She said McDermott taught her “not just a series of structures and routines but a way of seeing my students as my curriculum; it is my job to learn and master who they are as learners.”

ACE is part of the former Tyee High School, which was broken up into three separate, smaller schools several years back by the Highline District. But as Jodie Wiley, a teacher and site-based peer coach at ACE says, smaller schools and classrooms set the stage, but do not in themselves cause instruction to improve.

“We knew we needed to do more than just change the structure of the school. We knew we needed to change instruction, to change teaching and learning,” Wylie said in an e-mail. As the teachers got professional development from the center, she said, “Our expectations for our students rose, and students met those expectations.” This way, she said, her professional development “continues to grow with our students’ needs and our understanding, as teachers, of what strong instruction looks and sounds like.”

There are so many variables in play, it’s hard to prove causal relationships between changes in teaching or leadership techniques — both offered by CEL — and gains in student achievement. And literature from the center stops short of making such claims outright. But Stephen Fink, the executive director, said that research conducted in the Marysville School District and the Norwalk-La Mirada School District in Southern California, where the center has intervened, indicates the center’s work with school leaders has a positive effect.

The work focuses on, as the researchers put it, helping school leaders “increase their knowledge of what is being taught and their capacity to identify if it is being taught well.” Principals and district coaches were asked to analyze a 15-minute video of classroom instruction in literacy at two points in time, about a year apart. The researchers found significant statistical differences in scores from the first year to the second — that is, the school leaders appeared to improve in their ability to analyze the classroom instruction, and to provide feedback to teachers.

Research on CEL work continues. Although there has not yet been a randomized control study to find a causal link between CEL intervention and improved scores on assessments, Fink said the center “wouldn’t shy away at all” from such study. In general, he said, WASL scores have “trended upward” following all of CEL’s partnerships.

Meanwhile, the work of the center and its partners goes on, all springing from the goal of improving the classroom experience for teachers, and thus students, and ultimately helping to close the achievement gap.

Fink said the center looks forward to more partnerships with school districts, locally and nationally, in the future. “My strong feeling is that we have a responsibility to serve as many clients and school district leaders as we can serve,” he said. “The only limitation is the degree to which we can expand our capacity to meet their needs. We’re not going to jeopardize quality.”

Plans for the more immediate future include a Summer Leadership Institute June 23–28 and a Summer Coaching Institute July 14–17, both in Seattle.

Stacy Spector, principal of ACE, had high praise for the center’s assistance. She said in an e-mail that the coaching “has empowered our teachers to be both expert and learner,” increasing the transparency of their work, to students and fellow teachers. “Students know what they are learning, and how they are learning it, and why the learning is important and transferrable to other work and thinking.”

For more information on the center and its work, visit online at http://depts.washington.edu/uwcel/.