November 8, 2007

Fenske wins top environmental, occupational health award

By Kathy Hall

Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences

Richard Fenske, professor and associate chair of the Department of Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences in the School of Public Health and Community Medicine, has been recognized by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) and the International Society of Exposure Analysis (ISEA) for his contributions to the assessment and mitigation of human exposure to chemical hazards.

“It is unusual and a very pleasant surprise to win major awards in two disciplines, but it is a testimony to the interdisciplinary nature of our research in the Department of Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences,” Fenske said. “I share these awards with the exceptional students and staff who have worked with me over the years.”

In September the institute named Fenske the recipient of the 2006 NIOSH Director’s Award for Scientific Achievement in Occupational Safety and Health for his work in the development and application of a novel technique for assessing skin exposure to hazardous chemicals among agricultural workers.

The technique uses fluorescent tracers to detect pesticides on the skin after a worker has finished spraying. The tracers are mixed in with the pesticides or added to the pesticide spray tank used by the worker. Workers are then asked to stand under longwave ultraviolet light (black light), at which point any area where the tracer has deposited will appear to glow.

In 2004, Washington state initiated mandatory testing of pesticide handlers through a cholinesterase monitoring program, and found that about 20 percent of the tested workers had blood test results that required their employer to evaluate pesticide handling practices and about 5 percent had blood test levels that prompted temporary removal from pesticide handling.

“We are pleased to recognize Dr. Fenske’s leadership in this groundbreaking research with important practical applications,” said Dr. John Howard, NIOSH director. “It is particularly noteworthy that this technique offers a powerful tool for practitioners in reducing the risk of occupational illnesses among Hispanic workers, a significant and growing segment of the agricultural workforce. Especially among the segment of that population who may not be fluent in written English or Spanish, it serves a need for meaningful visual communication.”

Fenske said, “When my colleagues and I first used the fluorescent tracer technique in the early 1980s for our pesticide exposure research, we quickly came to appreciate its potential as a training tool. Seeing the fluorescent tracer glowing on their skin and clothes made an immediate impact on the pesticide handlers in our studies and provided them with a better understanding of how contamination had occurred.”

The fluorescent tracer technique is being used as a training method to help visually demonstrate to workers and employers the importance of proper use of personal protective equipment and good hygiene. A model for combining laboratory and field studies, the technology has been adopted by others in the United States and internationally.

The Pacific Northwest Agricultural Safety and Health (PNASH) Center, directed by Fenske, has been working with state pesticide education programs to adapt the method for hands-on training or quick demonstrations. In Cambodia, the technique was used to educate farmers about the hazards of skin exposures to pesticides. The center has published a pesticide safety training manual using the fluorescent tracer method (available in English and Spanish at http://depts.washington.edu/pnash/).

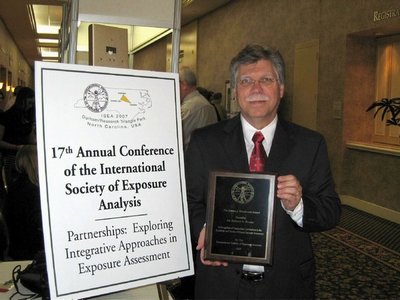

Last month ISEA presented Fenske with its 2007 Jerome J. Wesolowski Award for “sustained and outstanding contributions to the knowledge and practice of human exposure assessment.”

His plenary speech at the 17th Annual ISEA Conference was titled, “For Good Measure: Origins and Prospects of Exposure Science.” Because occupational exposures are often higher than environmental ones, many of the measuring techniques were pioneered by industrial hygienists in the workplace, and then adapted for environmental exposures.

Fenske and his colleagues at the PNASH Center pioneered measurements for children’s exposure to pesticides. For example, their methods for measuring organophosphate pesticides in house dust and pesticide metabolites in the urine of children have been used by other laboratories, and have been a model for other research groups, including UC Berkeley, Oregon Health and Sciences University, Wake Forest University, Rutgers University, and NIOSH.

In his address to ISEA he called for a reframing of exposure science to merge occupational and community exposure approaches, extend its reach to physical and microbiological agents of disease, integrate the work of social scientists to better characterize human behaviors, and partner with toxicologists who study gene-environment interactions.

His program at the UW recently changed its name from Industrial Hygiene to Exposure Sciences to acknowledge this trend.