October 11, 2007

Close to you: UW student actors learn to transfer stage technique to screen

Imagine you’re an actress doing Lady Macbeth’s sleepwalking scene. As you rant on about the blood on your hands, you’re trying to project a woman recoiling in horror from what she has done. Then the director stops the scene and sits you down in front of a screen where a close-up of your face fills the entire frame. You watch yourself perform.

“Good grief,” you’re likely to say, “I look like I’m shouting and mugging.”

Your reaction, says new drama school faculty member Andrew Tsao, is typical. And he should know. He’s been teaching theatrically-trained actors how to translate what they do to the screen for a number of years, and he’s watched them react in just that way to their first glimpse of themselves on screen.

Giving up on screen acting isn’t an option, however. Actors must be versatile if they want to make a living, and it isn’t stage acting that is likely to pay the bills. That’s why the drama school hired Tsao, a veteran director for television as well as theater. This fall he’s offering a course for the third-year students in the Professional Actor Training Program that he calls Screen Acting. It covers, he says, working in all kinds of media — film, television and electronic — anything that ends up on a screen.

“The camera is a device that I like to say is designed to look behind someone’s eyes,” Tsao says. “The landmark difference between acting for the screen and acting for the stage is the power of the close-up. That’s when everything changed, when the camera came into play and suddenly the actor’s face could be presented at a monumental scale to the audience.”

Tsao gives the classic example: “Do you love me?” the man asks the woman. “Of course I do,” she answers, after which the camera zooms in on her face and we know she’s lying.

But that presents a challenge to the actor, especially one used to working in theater. Live audiences watching Lady Macbeth sleepwalk won’t notice if her lips twitch or her eyes dart about. A bigger performance is needed to make it to the back row. But that same performance in close-up turns into scenery chewing.

“Screen acting,” Tsao says, “demands a kind of inner precision that ultimately on the surface looks very small, almost imperceptible.”

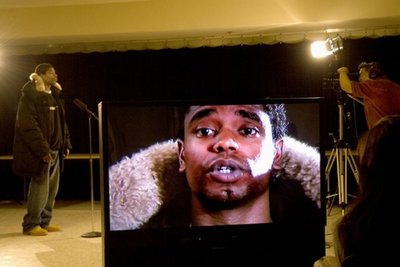

In working with actors to achieve that inner precision, Tsao has found, the problem instrument — the camera — also helps to provide a solution. After actors see what they look like, they can do their scenes over and over again as they learn to bring what they do to the proper scale. Moreover, thanks to digital equipment, the feedback is instantaneous. In class, Tsao plays the role of coach, trying to help each actor find his or her own way to an authentic screen performance. And, he encourages them to continue working on their own.

“We were able to get some new equipment through the Student Technology Fund grant that will allow student actors to take the gear out and work with each other on creating pieces,” he says. “They’ll be able to repeat and do different kinds of scenes and keep working to develop their skills, which I’m really thrilled about.”

Beyond the problem of scale, students of screen acting need to understand and learn to work with visually-oriented screenplays. The Lady Macbeth scene is, of course, from a play script, which Tsao says is a story told in words. Screenplays, on the other hand, are stories told in pictures.

Tsao cites the final scene from Casablanca as an example. Rick has shot Major Strasse at the airport as the local police chief, Louis, looks on. A group of policemen run up, asking for orders. There’s a close-up of Rick, followed by a close-up of Louis. Then Louis says, “Major Strasse has been shot. Round up the usual suspects,” after which there’s another close-up of Rick.

“It’s in those close-ups, not in the words, that we see Louis realize that he can’t turn Rick in, and Rick realize that Louis is not going to turn him in,” Tsao says. “And in those close-ups, volumes are spoken about friendship, loyalty, honor and all the things that Casablanca is about.”

To familiarize his student actors with screenplays, Tsao brings in a variety of them, along with DVDs with selected scenes. He teaches the students how to analyze the screenplays and also puts them through mock screen tests, often without warning. “I try to replicate what a typical day might be for them in New York or Los Angeles, as they look for work.”

About his students’ chances of finding that work, Tsao is upbeat.

” So much of what we try to do in professional actor training is to get people to be self generating artists,” he says. “This era is remarkable because of the digital revolution. This generation is reinventing what it means to be a star, what it means to be a working actor. You take YouTube or MySpace or any of those things — ten years ago it would have been absurd to think that anyone could make a career out of dramatic work on the Internet. Now it seems almost old fashioned. So what I find most challenging and rewarding about my work is, while I’m trying to prepare students for their opportunity in the industry at large, I also feel it’s just as important to prepare them for the opportunities they’ll make themselves.”

And many of those opportunities will be on the screen.

Tsao brings screen skills home to Seattle, UW

In joining the School of Drama’s faculty, Andrew Tsao is coming home — both to Seattle, where he grew up, and to the UW, where he earned his bachelor’s degree in 1982. Tsao is not a drama school alum, however; his degree is in political science.

“But I spent every waking hour I had outside of class here in the drama school,” he says. “I was a drama rat as an avocation.”

Once out of school, Tsao pursued drama “as a serious hobby,” and began to have some success in small projects. He moved to Los Angeles and enrolled in a graduate program in directing, which led to some work in regional theater.

Then he served as the artistic director of the New Harmony project, a writer’s development conference in New Harmony, Ind., where TV, film, musicals, plays are brought to be developed.

“I was directing one of the projects, and I met a writer we had brought out named Matt Williams. He was the writer and creator of Roseanne and Home Improvement. We met there and he saw my work and asked me to come to LA.”

From there was born a television directing career that has lasted 15 years, including directing numerous episodes of Home Improvement.

“Andrew decided to move his base back to the Seattle area, and he called to introduce himself,” said Sarah Nash Gates, director of the drama school. “Mark Jenkins (head of the Professional Actor Training Program) and I had lunch with him and he offered to teach a couple of classes in acting for the camera. Afterward, Mark was so impressed that he said he’d never teach that class again — Andrew was so much better.”

Tsao served as artist in residence last year at the drama school, teaching — in addition to screen acting — an undergraduate class on making drama out of non-dramatic material. “He learned about the Common Book, and made that the focus of the class,” Gates says.

He also introduced the idea of “reels” — 3 to 5-minute DVDs that actors create to showcase their screen abilities.

“We are thrilled to have Andrew on board,” Gates says. “He’s a dynamic and demanding teacher, and he’s really familiar with the business. We don’t intend to turn into a film school, but we recognize our graduate actors have to be ready to work anywhere. Andrew will play a crucial role in helping them learn the business.”