May 18, 2006

Journal subscription costs continue to climb

We love the online journals the UW Libraries provide. But do we realize how much they cost? How long will the Libraries be able to absorb relentless increases in subscription prices? A concerned Faculty Council on University Libraries (FCUL) asked for an update covering subscription costs and the emerging solutions that embrace less-expensive formats for scholarly communication.

This article contains questions asked by Beth Kerr, council chair, on behalf of the FCUL, and answered by Betsy Wilson, dean of University Libraries; Tim Jewell, director of information resources, collections and scholarly communication; and Mel DeSart, chair, Libraries Scholarly Communication Steering Committee.

What is the University Libraries budget for periodicals this 2005-2006 academic year?

Approximately $6.5 million just for periodicals. If other serials are added in, approximately $8.5 million.

Library subscription prices for periodicals (serials) continue to increase. How much have serial prices changed over the past 20 years?

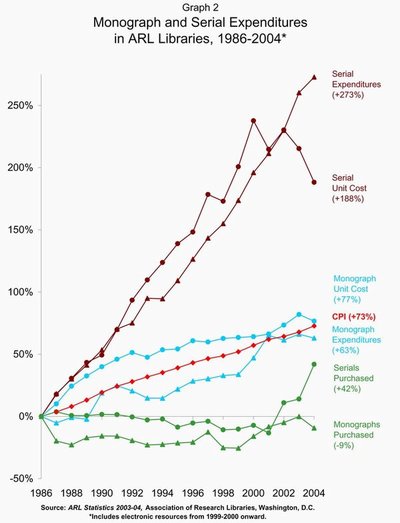

Solid estimates of average price increases are difficult to come by, but based on data collected by the Association of Research Libraries (ARL) for the 123 largest research libraries in North America, from 1986 to 2004 serial unit costs (serial expenditures divided by the number of serials a library purchases) increased 188 percent (see graph at right). As that graph illustrates, serial expenditures in ARL libraries also have risen nearly every year since 1986, up 273 percent from 1986. Meanwhile, over that same period, the Consumer Price Index increased only 73 percent.

What has University Libraries been doing to negotiate lower prices for subscriptions?

The primary price negotiation strategy the Libraries has at its disposal is to participate in group purchasing arrangements with other libraries. The Libraries currently participates in such arrangements for “bundles” of journals from Blackwell Science, Elsevier, Oxford University Press, Springer-Kluwer, and Wiley; advantages include annual “caps” on pricing increases and access to more titles than we could otherwise subscribe to, among others. Referring again to the graph, bundling largely explains the increase in number of serials purchased from 2002 to 2004, and the associated drop in serial unit cost.

Academic departments used to be able to work with their library liaisons to make subscribe/unsubscribe recommendations about individual journals. Has bundling subscriptions cut this flexibility?

Yes, a typical downside to bundling is that the Libraries may have to agree not to cancel any subscriptions for the duration of the agreement (typically from 3 to 5 years), or to do so only within narrow limits. In effect, that “exempts” journals in these packages from cancellation and puts the burden on other titles if journals must be cut.

How do journal subscription costs compare for for-profit and non-profit publishers? I expect most faculty are aware of “high cost” journals in their own areas but may not be aware of problems in other disciplines. Can you point to some of the very high cost publishers?

Based on data compiled by professors Ted Bergstrom of UC-Santa Barbara and Preston McAfee of CalTech for their Journal Cost-Effectiveness Web site (www.journalprices.com), the average 2004 price of 1,756 journals from not-for-profit publishers was $442.46, while the average price of 3,138 journals from for-profit publishers was $1,418.61. The average for-profit journal is over three times more expensive than the average not-for-profit title.

For a look at publishers with very high average journal prices, Bergstrom and McAfee’s data (http://www.hss.caltech.edu/~mcafee/Journal/Summary.pdf) is again useful. Looking only at publishers with a sampled output of 50 titles or more, John Wiley and Sons led the way with an average cost of $2,472.07 across 188 titles. Elsevier followed at $1,926.76 across 1007 titles, Academic Press (purchased by Elsevier) had 158 titles at $1,478.75, Springer’s 441 came in at $1,449.69 and Kluwer (who has now merged with Springer) had 553 titles that averaged $1,318.46.

Has the University Libraries needed to drop print versions in order to afford electronic versions?

Yes. While there is sometimes a discount for purchasing only the electronic versions of certain journals, buying print in addition may add 10 to 20 percent to the normal retail (print) price; since we lack the resources to buy both, and user demand for online access has been strong, we have cancelled a large number of print subscriptions — especially in the sciences and engineering.

What determines the number of years covered in electronic subscriptions?

Publishers largely determine how many years’ access is included with their subscriptions, and some publishers offer more or less access based on other terms. For instance, a publisher might provide access to a 10-year back-file in return for a multi-year subscription with limits on how much content can be cancelled, but only a couple of years if the right to cancel is fully retained.

Can we assume that we will have perpetual access to electronic subscriptions once a volume has been purchased? What steps are libraries taking to obtain and protect electronic access to older volumes of journals?

Obtaining “perpetual access” is also often complex or problematic. The Libraries always pursues the right to perpetual or ongoing access when negotiating licenses to e-journals, but may or may not succeed; when we succeed, the specific means for gaining that access may be unclear. In other words, we may have a right to ongoing access in the event of publisher bankruptcy or other circumstances, but have limited means of exercising those rights. Many research libraries, including the UW, are actively investigating new services aimed at insuring that access, such as LOCKSS and Portico — but these services will require paying ongoing charges.

There is increasing pressure to make published material more available to libraries unable to absorb high subscription costs, and to the public. One driving force behind changes to scholarly communication is taxpayer demand for access to funded research. An example is the National Institutes of Health policy that requests, but does not require, that NIH-funded investigators submit electronically to the NIH the final, peer-reviewed authors’ copies of their scientific manuscripts to become publicly available in the NIH Library of Medicine’s PubMed Central. How well is this policy working?

Not well at all. To date, the submission rate is only about 4 percent. Without requiring that papers be deposited in PubMed Central, the policy has no teeth. But legislation recently introduced into the Senate, if passed, would change that. The Federal Research Public Access Act (FRPAA) was introduced by senators John Cornyn of Texas and Joe Lieberman of Connecticut exactly one year to the day from when the NIH policy took effect. FRPAA would apply to all 11 federal government agencies that provide at least $100 million per year in research grants. Per the press release from Senator Cornyn, FRPAA would require those 11 agencies to:

- Require each researcher — funded totally or partially by the agency — to submit an electronic copy of the final manuscript that has been accepted for publication in a peer-reviewed journal;

- Ensure the manuscript is preserved in a stable, digital repository maintained by that agency or in another suitable repository that permits free public access, in- teroperability, and long-term preservation; and

- Require that free, online access to each taxpayer-funded manuscript be available as soon as possible, and no later than six months after its publication in a peer-re viewed journal.

Many library organizations and the Alliance for Taxpayer Access (www.taxpayeraccess.org) have already announced their support for the bill.

Some academic disciplines have national/international discipline-based repositories with open access for materials such as dissertations and preprints. For example, Cornell University Library hosts arXiv (arXiv.org), which covers physics, mathematics, quantitative biology, computer science, and nonlinear sciences. Have open access repositories influenced publication and subscription trends?

Apparently not. arXiv, which was started nearly 15 years ago and now contains over 367,000 e-prints, seemingly is not considered a threat to the health of publishers’ journals and subscriptions. The American Physical Society, which publishes 10 physics journals, actually hosts a mirror site for arXiv, rather than trying to shut it down.

Does University Libraries have plans to host discipline-based repositories?

Discipline-based? No, not at this time. But the Libraries does currently host an institutional repository and would be happy to work with UW faculty, departments, etc. interested in depositing content into that repository.

Some professional societies are actively seeking ways to keep journal costs low by establishing and supporting low cost or free, peer-reviewed, open access Web-based journals. For example, the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology established the Journal of Vision in 2001 (http://www.journalofvision.org). Likewise, some colleges and universities support free, peer-reviewed, open access Web-based journals. For example, Bryn Mawr Classical Review (http://ccat.sas.upenn.edu/bmcr/) has been online since 1990. Is University Libraries willing and able to encourage and support this development?

Definitely. The form that support takes will likely vary depending on the specific situation, but holding down journal costs benefits the UW Libraries and the entire UW community. If we can save money on journal purchases, it allows us to use those dollars saved to acquire other resources.

Nationally, research libraries plan to take the lead in providing alternative routes for scholarly communication. What steps are being taken now?

Research libraries use dozens of different methods to promote positive change in scholarly communication. We and our library organizations support efforts, such as the Federal Research Public Access Act, which would expand information access for communities that otherwise could not readily acquire it. We and our consortial partners enter joint agreements with publishers for access to their content. By “buying in bulk,” all the partnering institutions get more content for less money.

Libraries and departments either publish or are partnering in the publishing of journals, with the Bryn Mawr Classical Review mentioned above being an excellent example. We support organizations like SPARC, the Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition (www.arl.org/sparc), which works to catalyze change in scholarly communication nationally and internationally (e.g. SPARC Europe, and SPARC Japan is forthcoming). We set aside portions of our budgets specifically to support efforts that seek to buck the status quo. We work to educate our user communities about these issues and encourage participation by members of those communities in efforts to change a system that, while perhaps not broken, is at the very least dysfunctional.

The examples mentioned above are only a handful of the ways in which individuals, libraries, departments, institutions, consortia and national and international organizations are working to affect change in scholarly communication. But even with all this work, what we’re now doing doesn’t much more than scratch the surface of a multibillion dollar a year industry.

What models for scholarly communication do you expect to be in place in 10 years?

If the recent past is any indication, who knows? Ten years ago librarians were grumbling about serial prices and price increases, but just beginning to try to do something about them. Since then, SPARC was started as an advocacy organization for change, faculty and university administrations have become increasingly involved in scholarly communication issues, publisher mergers and bundling have changed how journals are packaged and sold, electronic subscriptions are more common than print at many research institutions, open access has developed into an alternative to traditional subscription models, and the federal government has gotten involved in these issues.

With all that having taken place in less than the last 10 years, about the only sure thing to say about the next 10 is that things won’t look the same as they do now. The primary goal for the Libraries is to be able to provide the members of the UW community with the content they need for their teaching, learning, and research. Current efforts on the scholarly communication front seem to be positive steps in enhancing our ability to do so. We will support that progress in whatever ways we can, will stay active and involved in supporting positive change in the system of scholarly communication, and encourage other members of the University of Washington to join us in advocating for changes that best support the needs of the UW and the broader educational and research community.