January 19, 2006

Comet dust from seven-year project is paydirt for UW astronomer

When the Stardust sample return canister was opened at Johnson Space Center in Houston Tuesday, Donald Brownlee was delighted by what he saw.

“It exceeds all expectations,” the UW astronomy professor said with excitement shortly after seeing into the canister for the first time. “It’s a huge success. We can see lots of impacts. There are big ones, there are small ones.”

Brownlee is principal investigator, or lead scientist, for Stardust, which returned to Earth in a spectacular re-entry early Sunday after a seven-year mission to collect particles from comet Wild 2, preserved from the formation of the solar system 4.6 billion years ago. It also captured samples of interstellar dust streaming into our solar system from other parts of the galaxy.

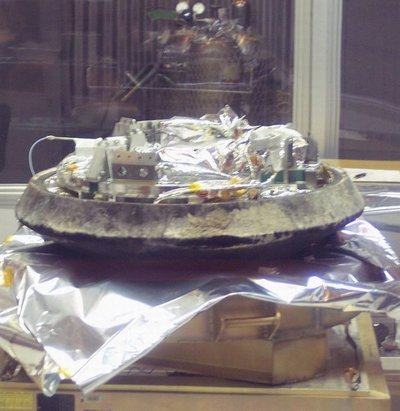

Brownlee calculated there might be more than a million microscopic specks of dust embedded in the aerogel collector inside the return canister. Aerogel, a remarkable material that is as much as 99.9 percent empty space, greatly reduced the stress of impact on the particles, he said. There are several larger particle tracks in the aerogel visible from several feet away, Brownlee said, and the black comet dust can be seen at the end of some of the larger tracks.

Scientists will now search the aerogel grid for dust samples, and more than 65,000 people have signed up to help in a project called Stardust@home, in which their home computers will examine images of tiny sections of the aerogel grid looking for dust particles.

The excitement of the canister opening was just the latest high-point in the dizzying success of the last week. Stardust lit up the night sky across the Western United States during its blazing, glorious return to Earth early Sunday. It also lit up the faces of all the scientists, engineers and technicians who for seven years or longer have lived and breathed the ambitious mission to capture specks of a comet and bring them back.

“It’s hard to describe the emotion. It was very exciting when I first saw the picture of the capsule in the mud. It almost brought a tear to my eye,” said Brownlee, who dreamed up the idea of a comet mission 25 years ago.

The return capsule made a soft parachute landing shortly after 3 a.m. MST on a sprawling military facility in the Utah desert southwest of Salt Lake City. Special helicopter-borne teams secured and recovered the capsule.

Brownlee expects the comet dust to carry evidence, preserved in the deep-freeze of deep space, about how the sun and the solar system formed 4.6 billion years ago.

It took the better part of 15 years to complete a viable plan for a comet mission and get approval from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. It took another four years to launch Stardust. Now, seven years later, the mission is a rousing success.

At its return, Brownlee had time to duck out of the Dugway Proving Ground command center and scour the sky for the fiery trail of the returning space capsule. Though the sky had been locked in thick winter storm clouds for most of the night, he was not disappointed. The clouds cleared long enough for stargazers to see the yellowish-orange fireball trailing across the heavens.

“It was almost like a fairy godmother sprinkling stardust in the sky. It was overwhelming,” he said.

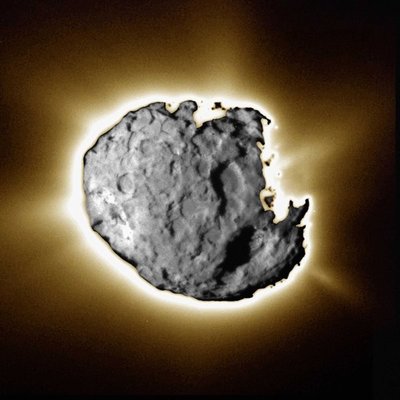

Stardust encountered Wild 2 (pronounced Vilt 2) on Jan. 2, 2004, beyond the orbit of Mars. It flew less than 150 miles from the comet’s nucleus to capture tiny grains of dust and snap close-up photographs of the comet’s main body. Though the grains were traveling faster than rifle bullets, they were not appreciably altered because the spacecraft’s collector used aerogel. The collector’s reverse side was used to capture bits of interstellar dust streaming into the solar system from other parts of the galaxy.

“What’s really exciting to me is that we soon expect to have this cosmic library in the laboratory so that we can try to read those records of our earliest history,” Brownlee said.

On its voyage, Stardust traveled 2.88 billion miles — the equivalent of more than 1 million trips from Los Angeles to New York. The mission became feasible after Wild 2 had a close encounter with Jupiter in 1974. The giant planet’s gravitational tug deflected the comet away from its previous path that went beyond Uranus, and brought it to the inner solar system where it could be reached by a spacecraft such as Stardust. Other spacecraft have visited comets, but Stardust is the only one designed to bring comet dust samples back to Earth.

“There’s a whole variety of scientific instruments, and people all over the world are going to be investigating these particles using the very best possible tools,” Brownlee said. “They will use electron microscopes, mass spectrometers and even nuclear accelerators. The largest instrument to be used that I know is Stanford University’s linear accelerator, which is 2 miles long.”

Stardust is part of NASA’s series of Discovery missions and is managed by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. Besides the UW, other major partners for the $212 million project are Lockheed Martin Space Systems; The Boeing Co.; Germany’s Max-Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics; NASA Ames Research Center; the University of Chicago; The Open University in England; and Johnson Space Center.

Brownlee likened the mission to some of the great seafaring adventures in human history.

“A lot of great explorers didn’t make it back,” he said. “This is the longest return voyage. Nothing has ever gone this far away and come back.

“In a very real sense, it is a great gift to be given the chance to do something like this.”

Who’s in a name?

The caller wanted information, specifically biographical information, about Donald Brownlee, the UW astronomy professor who dreamed up NASA’s Stardust mission to a comet and served as its principal investigator.

The caller to the Office of News and Information, it turned out, is also named Donald Brownlee, and he had more than a passing interest. He is a vice president in Washington, D.C., for a California-based company called Aerojet. In that capacity, he represents the company and its Redmond office in dealings with the federal government. The Redmond office — known in previous incarnations as Rocket Research, Olin Aerospace and Primex Technologies — made the propulsion system Stardust used to maneuver throughout its 2.88 billion-mile odyssey to capture dust from comet Wild 2.

The “other” Brownlee noted that he grew up in Spokane, that his parents hailed from Tacoma and his father graduated from UW in 1942 with a mechanical engineering degree.

“I’ve always considered my family’s roots to be in Washington,” he said.