March 31, 2005

New Kane collection spotlights artists of color

The UW and the Washington State Arts Commission’s Art in Public Places Program will dedicate a new collection of artworks by nine artists of color at 6 p.m. Thursday, April 7, in the main lobby of Kane Hall.

Called the Kane Hall Collection, the permanent exhibit is the culmination of a long-term effort instigated by UW minority students. “It really began back in 1991,” said Kurt Kiefer, campus art administrator. “A group of students talked to me then about how to make the physical campus more representative of the diverse people who work and study here.”

The original idea was to have a “Hall of Heroes” — busts of well-known people of color similar to those of white men found on the exterior of Suzzallo. But that idea was abandoned, Kiefer said, because of the difficulties of choosing who would be so honored and finding a suitable sculptor in the University’s price range.

The UW’s Public Art Commission then began working over several years with an artist who presented an idea that was ultimately rejected. Finally, a group of students spearheaded by Jaebadiah Gardner and Sumona das Gupta worked with the commission to develop the idea of a permanent collection.

The group has assembled artworks by some of the country’s most influential and respected artists of color. The Kane Hall Collection includes work by Barbara Carrasco, Rupert Garcia, Glenn Ligon, Hung Liu, James Luna, Roger Shimomura, Hulleah Tsinhnahjinnie, Carrie Mae Weems and Gu Xiong — all around the theme of identity.

“These are artists who deal with that theme in their work anyway,” Kiefer said. “These were existing works, not commissioned ones.”

Purchase of the works was made possible by the Washington State Arts Commission Art in Public Places Program. Each time the University constructs a new building, one-half percent of the total design and construction costs are set aside for artwork. All the money is pooled, so that art need not be sited at the new building. Kane Hall was chosen for the collection, Kiefer said, because it is one of the most public buildings on the campus.

Why did it take so long to bring the idea of art representing diversity to fruition? It wasn’t resistance, Kiefer said, but rather a desire to make the right choices. “This is the University’s first attempt at a physical representation of diversity,” he said, “and we wanted to be sure to do it right.”

The April 7 dedication will be followed by a slide lecture by James Luna at 7 p.m. in 220 Kane. The event is free and open to the public.

Kane Hall Collection Artists

Barbara Carrasco was born in El Paso, Texas, and has been creating art and murals since 1976 with numerous art collectives and community groups such as the Public Art Center, Chismearte Magazine, and the United Farm Workers Union. She received her bachelor’s Degree in 1978 from the University of California, Los Angeles and her MFA from the California Institute of the Arts in 1991. In 1998, she received a Getty Visual Arts Fellowship. Her work has been exhibited both nationally and internationally.

Rupert Garcia was one of the leading artists in the Chicano Movement of the late 1960s and early 70s, He participated in the formation of several seminal West Coast civil rights movement workshops and collectives, most notably the San Francisco Poster Workshop and la Galeria de la Raza. Garcia’s early work was primarily in the medium of silkscreen poster art, in which he developed a unique and colorful style of portraiture. From his earliest work, he expressed a commitment to the democratic and nationalist ideals of the Chicano Movement and created images in solidarity with other liberation movements, especially those in Indochina, Cuba and Native American communities in the United States. His work has been included in virtually every major exhibition of Chicano art in this country, as well as abroad. It has been collected in two major retrospective exhibitions: The Art of Rupert Garcia at San Francisco’s Mexican Museum in 1986 and Rupert Garcia: Prints and Posters, 1967-1990 mounted by the Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts at the Palace of the Legion of Honor in San Francisco. The bulk of Garcia’s work is housed in the National Archives of American Art at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

Glenn Ligon is a conceptual artist who chooses to create work in black and white as a way of pointing directly at racial stereotypes and expectations. At the same time it is a refusal to let his self-portraits be “colored.” In limiting his palette or restricting his photographs, Ligon reminds us of the polarized race relations that still plague the United States 150 years after the abolition of slavery.

Hung Liu was born in China in 1948. She was a high school senior when she, along with thousands of other educated citizens, was forcibly “re-educated” as part of the Cultural Revolution. Hung was sent to pick rice in the countryside for four years. When she was allowed to return to Beijing, she earned a BFA from the prestigious Central Academy of Fine Art in 1975. As a state-sponsored artist Hung was ordered to paint ‘Tractor Art’ (pure realism glorifying the Mao Regime and easily understood by the masses), but she nonetheless discovered and fell in love with old photographs: fading portraits of Emperors, their wives and concubines. These sad faces without hope have the same look as the faces of present day Chinese women toiling at hard labor. They contradicted the government’s upbeat version of Chinese history. State officials were not amused when she began inserting contradictory references into her painting, yet Hung’s personal experience confirmed to her the reality beneath the propaganda. In 1984 she was permitted to emigrate and in 1986 Hung earned an MFA at UC San Diego. Since 1986 she has been on the faculty of Mills College, Calif., and presently chairs the Department of Painting.

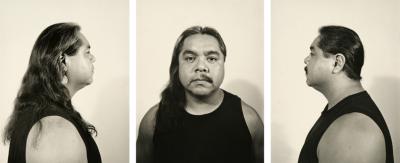

James Luna is a Luiseño/Diegueño Indian who lives on the La Jolla Indian Reservation in San Diego County, Calif. Luna believes that installation/performance art (in which he employs a variety of media such as objects, audio, video and slides) “offers an opportunity like no other for Native people to express themselves without compromise in the traditional Indian art forms of ceremony, dance, oral narrative and contemporary thought.” His installations have been described as transforming gallery spaces into battlefields where the audience is confronted with the nature of cultural identity, the tensions generated by cultural isolation, and the dangers of cultural misinterpretation — all from a Native perspective. Using handmade and found objects, Luna creates environments that function as both aesthetic and political statements. As a Rez resident, he draws from personal experience and probes emotions surrounding the way people are perceived with their cultures. In his artwork, Luna addresses the mythology of what it means to be Indian in contemporary society and works to expose the hypocrisy of the dominant society that trivializes Indian people as romantic stereotypes. Luna’s installation/performance art is provocative, often dealing with difficult issues affecting Indians. He confronts these issues head-on, often using humor and satire as both a counterbalance and salve. Demanding a level of audience participation with all his work, he consistently challenges viewers to examine deeply their own prejudices.

Roger Shimomura’s work is an aesthetic and political comparison between contemporary America and traditional Japan. Using images from both cultures, Shimomura creates a complicated layering of pictorial information and social observation. As his paintings and prints are interpreted and decoded by the viewer, Shimomura’s tangled intentions are revealed in a subtly political way. He says, “This direction required many new resources and led me to practicing a form of self-legalized visual larceny. Using images from my past and immediate environments, from earlier and current work and using them as cultural metaphors, I became a dispassionate viewer of my own layering system. From there I saw the relationship between the merchandise I used to covet and draw from old Sears catalogues and the bizarre collection of objects that now fill my house. So did I also see the relationship between misleading reproductions from art history books and my mom’s old issues of Woman’s Day, between the music of the John Coltrane Quartet and the Salvation Army Band, between the stories that my grandmother left and the editorials in the local newspaper, between a meal of steamed black cod and the Colonel’s Wingdinger, between vintage Kurosawa and Johnny Socko, between Masterpiece Theatre and Pee-Wee’s Playhouse, between an Oreo cookie and a Chiquita Banana and between Minnie Mouse and one of Utamaro’s beauties.”

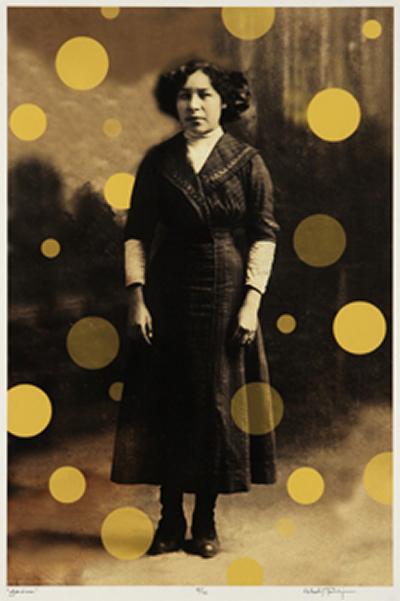

Hulleah Tsinhnahjinnie was born in 1954 into the Bear and Raccoon clans of the Seminole and Muskogee Nations. She grew up in Phoenix and Rough Rock, Ariz., and later attended the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, N.M. She received her BFA from California College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland in 1981 and was a Chancellor’s Fellow at from University of California at Irvine for her MFA. Tsinhnahjinnie has taught at the University of California at Davis, San Francisco State University, San Francisco Art Institute and the Institute of American Indian Art.

Carrie Mae Weems, In the course of her 15-year photographic career, has created a rich array of documentary series, still lifes, narrative tableaux, and installation works. Often mixing hard realities with a personal vision, some works are pointedly political, bitter with the pain of past injustices and still prevalent prejudices, while other work is playful and even celebratory. Weems’ interest in art was sparked by those African-American artists who revealed something special about the black experience, who spoke to and about the rich, broad spectrum of her culture. One key body of work that she mentions frequently as an inspiration is The Sweet Flypaper of Life, a 1955 photo and prose-poem essay by photographer Roy DeCarava and poet Langston Hughes — both African-American New Yorkers. Examining the relationship of Weems’ work to DeCarava’s, critic bell hooks has written: “She was particularly inspired by DeCarava’s visual representations of black subjects that invert the dominant culture’s aesthetic. DeCarava endeavored to reframe the black image within a subversive politics of representation that challenged the logic of racist colonization and dehumanization.”

Gu Xiong is a multimedia artist originally from Chongquing, Sichuan, in the People’s Republic of China. In 1972, during the Cultural Revolution, he was sent to the countryside with millions of other youths and forced into “re-education” with peasant teachers. He labored in the fields under extremely primitive conditions for four years. By the light of a kerosene lantern, he started to draw the people and objects around him. Drawing became an obsession and gave him strength. After being allowed to return to the city, he earned a BFA and MFA at the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute where he also taught traditional woodcut printmaking. In 1989, Gu Xiong finally had to flee China as a result of his participation in Beijing’s China/Avant Garde show and in the Tianamen Square demonstration. Since 1992, he has been an instructor of printmaking and drawing at the Emily Carr Institute. In the fall of 2004, he was a featured artist at the Shanghai Biennale, China’s foremost international exhibition for contemporary art. His massive photo installation, I am Shanghainese, was mounted on the exterior walls of the Shanghai Art Museum.