July 22, 2004

Northwest’s rural beauty hides economic crisis, study finds

Urbanites escaping to the majestic beauty of the rural Northwest this summer may not realize that the families living in those scenic communities face a growing struggle to hang on.

A yearlong study to be released today (July 22) warns that chronic unemployment and shrinking access to education and services threaten the future of families in the rural Northwest, where almost half the children already live in poverty.

More than 100 residents of eight small towns in Washington and Oregon guided the researchers in compiling a unique portrait of Northwest rural realities.

“Rural life in Washington represents much of what Americans would like to see in every city or town — a strong sense of community, safe neighborhoods and a respite from the woes of urban life,” said co-author Lori Pfingst of the University of Washington. “We found that parents really love these communities and are committed to raising their children there, but the economic reality of rural towns makes it increasingly difficult to stay . We need to rethink some of our policies to help rural communities become sustainable again.”

Jobs, of course, were foremost among concerns for the rural Northwest, where nearly half the counties have endured 8 percent-plus unemployment for at least a decade.

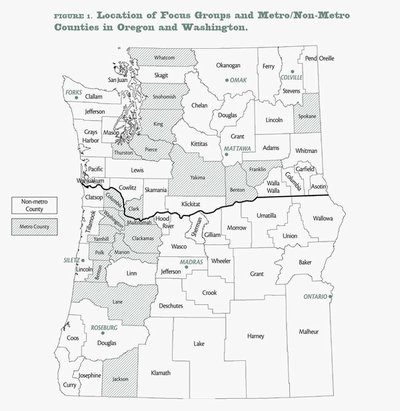

The 36-page report, “Listening to Learn: Stories from Rural Northwest Families,” was prepared by Washington Kids Count and Children First For Oregon. Focusing on rural families as part of a national effort funded by the Annie E. Casey Foundation, the researchers mined information from focus groups and community leaders in eight diverse Northwest towns — four each in Washington and Oregon.

Among their key findings:

- Child care. Small towns lack enough quality day care choices with flexible hours for the 62 percent of rural Northwest mothers of children under 6 who work or are looking for work. Result: many rural family incomes stay low.

- Education. College enrollment declined in three out of the eight Northwest towns in the study between 1990 and 2000 as budget-crunched states raised tuition and cut class offerings. Dwindling access to education compounds the economic distress, with the lack of an educated work force making it ever harder to attract new businesses.

- Diversity. Designing a recovery policy for the rural Northwest is complicated by the varied nature of such communities. The four Washington towns in the study ranged from Forks, where a third of the workers hold government jobs, to Mattawa, where the majority of jobs are agricultural and 90 percent of the residents are Hispanic (half of whom arrived in the United States between 1990 and 2000).

Other major barriers include limited access to health care (Mattawa, for example, lies 28 miles from any hospital), lack of public transportation and inadequate opportunities for middle- and secondary-school children. And coloring the entire picture is chronic rural unemployment, which prevailed even through the nation’s late-1990s economic boom and shows signs of persisting through the current recovery.

Yet most of the families interviewed expressed hope and determination. Indeed, the rural Northwest population continues to grow — outpacing many other U.S. regions — even as Northwest rural economies falter and opportunities for rural children diminish.

Parents told the researchers that they are determined to raise their children in rural areas, citing the safety of small towns and the natural beauty of their surroundings.

“Pretty much everybody knows everybody,” said one Omak parent in the study, who took delight in the fact that the local newspaper prints a story “if your dog’s barking at night.”

How to enable such families and towns to thrive? The study authors recommend policies that build on each community’s strengths, which include populations of people who like rural life and are willing to help one another in a crisis.

For starters, the researchers call for readjusting state programs that overlook the realities of rural life, such as current rules that require a welfare recipient to generate 10 job contacts each week (even in areas with few employers). State agencies also could prioritize services essential to rural areas (such as transportation to specialized medical care) and adjust existing childcare policies with rural realities in mind.

“The fact that so many children are affected by the distressed economy of rural Washington is disturbing and deserves the public’s attention,” said Pfingst, a researcher with the Human Services Policy Center at the UW’s Evans School of Public Affairs. “These kids deserve the same opportunities as their urban counterparts.”

###

For more information, contact Pfingst at (206) 616-1506, cell (206) 650-3471 or pfingst@u.washington.edu. The study is posted at the Human Services Policy Center Web site, www.hspc.org.

Officials listed below can discuss local conditions in more detail and help identify residents to interview on topics raised in the study:

Washington towns studied:

- Colville: One quarter of adults work in education, health and social services. CONTACT: Tiane Shoemaker, Chamber of Commerce president, (509) 685-0146.

- Forks: A logging community in transition. CONTACT: Irene Smith, Forks Elementary School counselor, (360) 374-6262 x445 or (home) (360) 374-9846.

- Mattawa: An agricultural community that is predominately Hispanic. CONTACT: Delcine Mesa-Johnson, assistant superintendent of Wahluke Schools, (509) 932-4423

- Omak: Built on logging and agriculture, now with many seasonal workers. CONTACT: Erin Mundinger, Okanogan Worksource manager, (509) 826-7545. .

Oregon towns studied:

- Madras: Once “the mint capital of the world,” now turning to manufacturing and tourism. CONTACT: Angie Spannaus, Central Oregon Partnership, (541) 475-0301.

- Ontario: Major industries are education, health, social services and manufacturing. CONTACT: Sue Robinett, Malheur County Child Development Center, (541) 889-2393.

- Roseburg: Douglas County seat serves as a focus for nearby small towns. CONTACT: Mike Fieldman, Umpqua Community Action Network, (541) 672-3421.

- Siletz: Predominant industries are education, health, social services, arts and tourism. CONTACT: Tina Kotek, Children First for Oregon, (503) 236-9754.