January 16, 2003

Book traces history of American popular music

As a graduate student teaching Introduction to Music, Larry Starr hit upon a teaching method that he found worked really well. After teaching a particular song form in classical music, he would bring in a song by, say, the Beatles or the Beach Boys and tell his class, “Here’s an example of that form that you might be familiar with.”

“It made these musical abstractions very real,” Starr says, “and it also made a connection between what to the students was distant art music on a pedestal and the pop music they were listening to.”

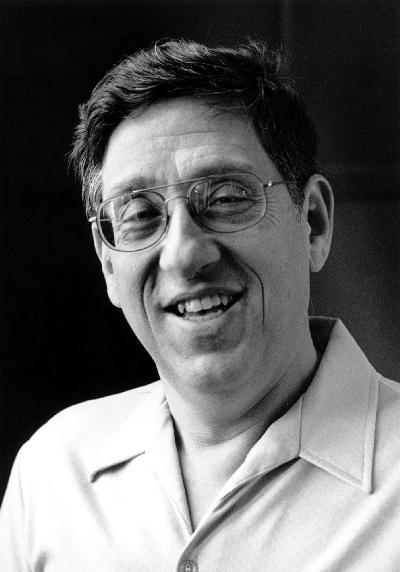

Starr didn’t know it at the time, but he was laying the foundation for his later career, when he began teaching whole classes in popular music. Now he is the co-author of a book on the subject, American Popular Music: From Minstrelsy to MTV.

A music historian, Starr has done most of his scholarly work on the composers Charles Ives, Aaron Copland and George Gershwin, but these days he knows just as much about Bob Dylan, Paul McCartney and Brian Wilson. Moreover, he thinks the latter composers are just as worthy of attention as the former. The fact that, like Aretha Franklin, they haven’t gotten enough respect is, he says, a function of a wall that exists in American culture — a wall that divides art music and popular music.

“I think that wall is more a cultural than a purely musical phenomenon,” Starr says. “What I mean by that is that one can take a song by Cole Porter, Lennon/McCartney, Paul Simon, and look at it exactly the same way that you’d look at a Schubert lied and find the same reasons to admire it. You’d find that the music responds beautifully to the structure and meaning of the lyrics and that there is melodic and harmonic sophistication. The songs may well be written for different purposes and tend to be heard in different contexts, but the question of what qualifies as art here is very very permeable.”

Starr came to that conclusion early in his career. Assigned to teach 20th century music at his first job — at the State University of New York, Stony Brook — he learned that although the course description mentioned jazz, no jazz had been taught by his predecessors. So he gave himself a crash course in the subject and incorporated a week of jazz into the class. Later, he added pop music. By the early 80s, shortly after his arrival at the UW, Starr felt it was time for a popular music class — a class that found a willing audience among both music majors and non-music majors.

Still, Starr might never have written a book about popular music had it not been for two former colleagues — Christopher Waterman, who also taught classes in popular music here, and Daniel Neuman, former music school director.

“One day Dan cornered Chris and myself in the hall and said, ‘You know, you two should write a book on American popular music. You’ll make a lot of money.’ We’ll see if that turns out to be true,” Starr says.

Waterman, who is now at UCLA (as is Neuman), is an ethnomusicologist whose work emphasizes the cultural context of music. Most of Starr’s work, on the other hand, involves close analysis of particular pieces of music. Their book, then, is both an examination of the cultural roots of American popular music and a close analysis of selected songs — some of which are contained on two accompanying CDs.

“We call our approach themes and streams,” Starr says. “The themes deal with such issues as music and identity, the influence of technology and the methods of the music business. The three streams we identify are European American, African American and Latin American.”

The themes and streams are introduced in the first chapter, after which a chronological narrative traces the history of popular music through the end of the 20th century. Sprinkled throughout are boxes describing the careers of key musicians and groups, as well as “Listening and Analysis” segments on particular songs. Why one song and not another?

Starr says the songs were chosen because they were representative of a particular artist or group’s style and also because they had enough interesting traits to make them more than generic.

Out of Bob Dylan’s prodigious output, for example, Starr chose Like A Rolling Stone for close analysis. It was, he says, an obvious choice. To begin with, it changed Dylan from an important folk artist whose songs other people could turn into pop records (as Peter, Paul and Mary did with Blowin’ in the Wind) to being a mainstream pop artist himself.

But the song was also important in itself. It was — at 6 minutes — by far the longest pop record ever made at the time. Whereas before, radio stations would play nothing longer than 3 minutes, afterward they played songs even longer than this one (The Beatles’ Hey Jude, for example, was almost 8 minutes long). It also featured Dylan with an electric band and led to a new style called folk rock.

“Yet it is also an archetypal Bob Dylan song,” Starr says. “It’s full of poetic imagery; it’s full of social commentary; it is representative of him at the same time that it is a uniquely important record.”

Starr and his co-author hope that listening closely to songs such as Like A Rolling Stone will help the book’s audience develop critical listening skills.

“As a musician you have sort of a strange relationship to the culture at large,” he says. “You love the fact that music is so prevalent, that so many people need and use music, and yet you really wish that they were listening more carefully, that they would use it as something other than background. The pervasiveness of music has led to sort of a reduction of critically aware listening, and critically aware audiences are necessary for any sort of music to flourish.”

Starr will be at University Book Store for a talk and book signing at 4 p.m., Thursday, Jan. 23.