December 5, 2002

Surviving Roundup 101: Teaching guru Don Wulff honored

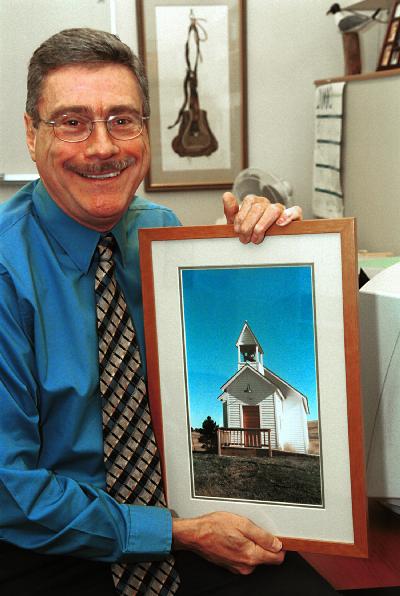

On the wall in Don Wulff’s office is a framed photograph of a tiny schoolhouse in Montana. That schoolhouse — now a museum — was Wulff’s first experience of education. Back then, he lived on a farm 16 miles from the nearest town with his parents and two siblings. The school was three miles away, and in the winter when the snow made roads impassable, his mother would load the kids on a horse and ride with them to the school.

“She rode three miles there and three miles back, then did it all over again at the end of the day,” Wulff says.

Later, that same mother fought to have her children attend school in town, then piled them into the car to get them there and back every day.

Mrs. Wulff clearly communicated something about the value of education to her children, two of whom hold doctorates today.

“Neither of my parents ever went to college,” Wulff says, “yet they insisted that we get the best education possible and made sacrifices to see that it happened.”

So maybe it isn’t surprising that Wulff grew up to be first a teacher and then a teacher of teachers. For the past 19 years he’s been at the Center for Instructional Development and Research (CIDR), the campus organization devoted to helping faculty and teaching assistants be the best teachers they can be. Starting as a graduate student, he has risen through the ranks to become director a year and a half ago.

And recently, Wulff was honored for his commitment to education on a national level. His professional organization, the Professional Organization and Development Network in Higher Education (POD), gave him the Bob Pierleoni Spirit of POD Award, an honor that is essentially for lifetime achievement.

Not bad for a guy who started school in the middle of nowhere and started his teaching career at a high school in Roundup, Montana.

“That’s where I learned to teach, I’m telling you, when I walked in and had 18 and 19 year olds sitting in my classroom and I was 20,” Wulff says of Roundup. “I have a little speech I sometimes give as a guest lecturer. It’s called ‘Effective Teaching and Learning, or, How to Survive your First Year in Roundup, Montana.’ That year broke me in.”

What he learned, he says, is that it’s not enough for a teacher to be a friend to his students. Rather, it’s a balance between earning credibility for yourself and having high expectations of them. Only after those things are established can the interpersonal dimension be added.

“That was a hard lesson to learn,” Wulff says. “It took me one year.”

But he stuck it out, continuing to teach English, speech and drama at Roundup, and then at Missoula, for a total of 16 years. He had earned his master’s while continuing to teach when he came to a crossroads.

“I felt as if I’d given what I had to give to teaching high school,” Wulff says. “I wanted to do something for myself, to try to better myself.”

But there were risks involved. In his mid-30s by then, Wulff had a house, a family, retirement funds — in short, a secure life. Moving to Seattle for a doctoral program at the UW would throw a monkey wrench in all that. And Wulff inadvertently made it harder when he fell asleep during the Graduate Record Exam (he’d been up late working on high school drama production) and earned less than stellar verbal scores. That forced him to enter the graduate program in speech communication without a teaching assistantship.

Undaunted, Wulff set out to prove himself and soon earned his place. He specialized in instructional communication and came to CIDR as a graduate student in 1984, shortly after it had undergone a major restructuring. He’s been there ever since.

“I like to tell our new staff and graduate student consultants that I’ve held every consulting role here,” Wulff says.

Some things about CIDR have remained constant since the beginning, and one of those things comes straight out of Wulff’s dissertation, which was on teaching effectiveness. He interviewed winners of the UW’s Distinguished Teaching Award in an effort to learn what makes a teacher effective.

“What I found out was that effective teachers are able to balance the content, the students’ needs and expectations and their own needs and expectations in ways that they can achieve their teaching/learning goals,” he says. “So sometimes we talk about balance, sometimes we talk about adaptability, but the whole model has permeated our work here at CIDR. It says there are few answers beyond a given context. You have to find out what the instructor is like, what the students are like and what the content is and then figure out how to help the instructor find the balance.”

One thing that has changed at CIDR, however, is its place at the University. Wulff says that when the center began, the focus on teaching improvement was “like swimming against the current. What made our work especially challenging was the ongoing need to seek an appropriate balance to fit the teaching and research missions of this institution.”

But then, what’s that to a guy who once rode horseback in the snow just to get to school? Besides, it’s no longer as true as it once was. “Now there are many more people on campus focused on teaching issues,” Wulff says, “and as a result, the need for communication and especially collaboration is absolutely essential.”

The concern of other units with teaching points to the success of CIDR, a success that Wulff has certainly been a big part of. But he won’t take the credit for that — or even for his career achievement award — alone.

“The CIDR staff are fantastic,” he says. “We added up the years of experience they have and it’s something like 95 years among six people. I really see this Pierleoni award as representing not just what I do but what they do too.”